Custom Walk in Toledo, Spain by serbanescumariananarcisa_65374 created on 2025-07-30

Guide Location: Spain » Toledo

Guide Type: Custom Walk

# of Sights: 16

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.9 Km or 2.4 Miles

Share Key: D2VWQ

Guide Type: Custom Walk

# of Sights: 16

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.9 Km or 2.4 Miles

Share Key: D2VWQ

How It Works

Please retrieve this walk in the GPSmyCity app. Once done, the app will guide you from one tour stop to the next as if you had a personal tour guide. If you created the walk on this website or come to the page via a link, please follow the instructions below to retrieve the walk in the app.

Retrieve This Walk in App

Step 1. Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" on Apple App Store or Google Play Store.

Step 2. In the GPSmyCity app, download(or launch) the guide "Toledo Map and Walking Tours".

Step 3. Tap the menu button located at upper right corner of the "Walks" screen and select "Retrieve custom walk". Enter the share key: D2VWQ

1) Plaza de Zocodover (Zocodover Square)

The name Zocodover has a curious ring to it, and for good reason. It comes from the Arabic word for “market of the beasts,” a straightforward reminder that what is today a lively plaza was once the place where horses, donkeys, and mules were traded. For medieval Toledo, this square was less a backdrop for leisurely promenades and more a utilitarian hub-part fairground, part marketplace, and, on occasion, even a bullring. The townspeople once entertained themselves here with cucañas, competitions to smash hanging clay pots, sometimes filled with sweets and, rather less delightfully, dead rats.

Commerce and spectacle were only half the story. Zocodover became Toledo’s civic stage, the space where victories were announced and grim punishments were carried out. During the Spanish Inquisition, public autos-de-fe were staged in the square, spectacles of fear designed to assert orthodoxy. Earlier, in the centuries of Muslim rule, the square thrived as a bustling bazaar filled with fabrics, spices, and voices in Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin dialects. When King Alfonso VI captured Toledo in 1085, reestablishing it as a Christian stronghold, the square did not lose its centrality; it simply changed costume, adapting to new rulers while retaining its role as the beating heart of the city.

The architecture surrounding the plaza tells this story in brick and stone. Over time, elegant arcaded buildings rose to enclose the space, offering shade for shoppers and a frame for processions. The tradition of the Tuesday market still endures, spilling into the nearby Merchants’ Promenade. Cafés and shops now inhabit the ground floors, but the sense of community gathering has not faded.

Stand amid the arcades, listen to the chatter, and imagine the swirl of animals, merchants, nobles, and pilgrims who once crowded the same cobblestones-proof that in Toledo, history prefers to be lived out loud.

Commerce and spectacle were only half the story. Zocodover became Toledo’s civic stage, the space where victories were announced and grim punishments were carried out. During the Spanish Inquisition, public autos-de-fe were staged in the square, spectacles of fear designed to assert orthodoxy. Earlier, in the centuries of Muslim rule, the square thrived as a bustling bazaar filled with fabrics, spices, and voices in Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin dialects. When King Alfonso VI captured Toledo in 1085, reestablishing it as a Christian stronghold, the square did not lose its centrality; it simply changed costume, adapting to new rulers while retaining its role as the beating heart of the city.

The architecture surrounding the plaza tells this story in brick and stone. Over time, elegant arcaded buildings rose to enclose the space, offering shade for shoppers and a frame for processions. The tradition of the Tuesday market still endures, spilling into the nearby Merchants’ Promenade. Cafés and shops now inhabit the ground floors, but the sense of community gathering has not faded.

Stand amid the arcades, listen to the chatter, and imagine the swirl of animals, merchants, nobles, and pilgrims who once crowded the same cobblestones-proof that in Toledo, history prefers to be lived out loud.

2) Alcazar Fortress (must see)

The Alcázar of Toledo has never been content to play a single role. Rising on the city’s highest hill above the sweep of the Tagus River, it has been a Roman fortress, a Visigothic palace, a Muslim stronghold, a Renaissance residence for monarchs, and finally a national symbol forged in fire and war. Its name, “Alcázar,” comes from the Arabic al-qasr, meaning “castle” or “fortress,” a reminder that Toledo was once a jewel of Al-Andalus. Yet even before the Moors, the Romans had fortified this commanding site in the 3rd century. Later, the Visigoths ruled from its walls, and after the Christian reconquest of 1085, King Alfonso VI of Castile rebuilt the structure, weaving it into the reborn Christian city.

By the 16th century, Toledo’s prominence as the capital of Castile inspired Emperor Charles V and his son Philip II to commission major renovations. They entrusted architects such as Alonso de Covarrubias and Juan de Herrera-masters of Renaissance classicism and austere symmetry-to transform the fortress into a palace that would rival anything in Europe. The result was a massive rectangular building anchored by four imposing towers at its corners, its stern Herrerian façade contrasting with the more flamboyant baroque style visible elsewhere in Toledo.

Yet the Alcázar is remembered not only for its stones but also for its stories. During the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Republican forces besieged the fortress for over two months. Inside, Colonel José Moscardó Ituarte held out with Nationalist supporters. In a tragic episode that became legendary, Moscardó’s son Luis was captured and executed after refusing to plead with his father to surrender. When Nationalist troops finally lifted the siege, the Alcázar lay in ruins, but its battered walls came to symbolize defiance and sacrifice for Franco’s regime. Rebuilt after the war, the scars were left visible as reminders of the city’s ordeal.

Today, the Alcázar is home to the Army Museum and the Castilla-La Mancha Regional Library. Tourists can wander its grand halls, admire centuries of military artifacts, and step out onto the ramparts for sweeping views of Toledo’s tangle of stone streets and the river below. A visit here is less about a single period and more about seeing how power, war, and memory have been carved into one commanding monument.

By the 16th century, Toledo’s prominence as the capital of Castile inspired Emperor Charles V and his son Philip II to commission major renovations. They entrusted architects such as Alonso de Covarrubias and Juan de Herrera-masters of Renaissance classicism and austere symmetry-to transform the fortress into a palace that would rival anything in Europe. The result was a massive rectangular building anchored by four imposing towers at its corners, its stern Herrerian façade contrasting with the more flamboyant baroque style visible elsewhere in Toledo.

Yet the Alcázar is remembered not only for its stones but also for its stories. During the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Republican forces besieged the fortress for over two months. Inside, Colonel José Moscardó Ituarte held out with Nationalist supporters. In a tragic episode that became legendary, Moscardó’s son Luis was captured and executed after refusing to plead with his father to surrender. When Nationalist troops finally lifted the siege, the Alcázar lay in ruins, but its battered walls came to symbolize defiance and sacrifice for Franco’s regime. Rebuilt after the war, the scars were left visible as reminders of the city’s ordeal.

Today, the Alcázar is home to the Army Museum and the Castilla-La Mancha Regional Library. Tourists can wander its grand halls, admire centuries of military artifacts, and step out onto the ramparts for sweeping views of Toledo’s tangle of stone streets and the river below. A visit here is less about a single period and more about seeing how power, war, and memory have been carved into one commanding monument.

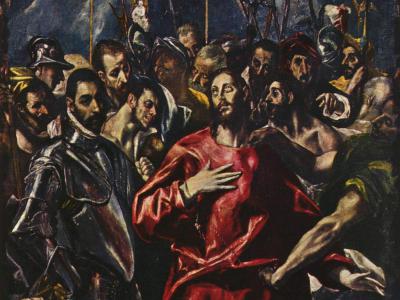

3) The Disrobing of Christ Painting at Toledo Cathedral

The painting "The Disrobing of Christ" by Domenikos Theotocópoulos (El Greco) took two years to create. It was done on commission for the high altar of the sacristy of the Cathedral of Toledo. It was finished in 1579, but it was received not without controversy. The painting was valued at 950 ducats. El Greco was paid only 350.

The commissioners were displeased at some of the figures and colors in the painting. El Greco agreed to remove some of the figures but failed to do so. While the church fathers were not completely satisfied with the work, critics have acclaimed the painting as a "masterpiece of extraordinary originality."

The canvas is alive with color and movement. Christ, in the center of the vertically oriented scene, wears the purplish red robes of martyrdom. His expression is elevated and serene. His tormentors, all clad in dark colors or armor, press around him. They appear agitated. They point and gesticulate. The three Marys look on in anguish.

More than 17 versions of the painting are known to exist. The Disrobing immediately became hugely successful. Replica versions, including at least two by the Master, can be found in museums such as the National Gallery in Oslo, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, and Upton House in Warwickshire, England.

The commissioners were displeased at some of the figures and colors in the painting. El Greco agreed to remove some of the figures but failed to do so. While the church fathers were not completely satisfied with the work, critics have acclaimed the painting as a "masterpiece of extraordinary originality."

The canvas is alive with color and movement. Christ, in the center of the vertically oriented scene, wears the purplish red robes of martyrdom. His expression is elevated and serene. His tormentors, all clad in dark colors or armor, press around him. They appear agitated. They point and gesticulate. The three Marys look on in anguish.

More than 17 versions of the painting are known to exist. The Disrobing immediately became hugely successful. Replica versions, including at least two by the Master, can be found in museums such as the National Gallery in Oslo, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, and Upton House in Warwickshire, England.

4) Toledo Cathedral and Monstrance of Arfe (must see)

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of Toledo, often simply called Toledo Cathedral, is more than a place of worship-it is a monument that mirrors the city’s long and complex history. The site itself had already been sacred for centuries before the Gothic masterpiece rose above Toledo. In the 6th century, under the Visigothic Kingdom, a church dedicated to Saint Mary was consecrated here. When Muslim forces seized the city in 711, the church was replaced with a mosque, its qibla wall oriented toward Mecca and its minaret rising over the skyline. Even today, attentive visitors can still pick out traces of these earlier layers: a Visigothic column in the Chapel of Saint Lucy, or the horseshoe arches that echo Islamic design. When King Alfonso VI of León and Castile retook Toledo in 1085, he converted the mosque into a Christian place of worship, setting the stage for an even greater project.

That project began in 1226, under the reign of King Ferdinand III, who envisioned a grand cathedral to symbolize the triumph of Christianity and the new power of Castile. For nearly two centuries, master architects, including Master Martín and the renowned Alonso de Covarrubias, labored to complete the vast structure. The result was one of the largest Gothic cathedrals in Europe, with five sweeping naves, a towering spire, and a façade adorned with ornate portals bearing names as dramatic as their sculptures: the Gate of Forgiveness, the Gate of the Last Judgment, and the ominous Gate of Hell. The building itself embodies Gothic grandeur, yet whispers of earlier civilizations remain embedded in its walls.

Inside, the cathedral unfolds as a treasury of Spanish art. The high altar rises like a forest of gilded wood and sculpted scenes from Christ’s Passion, while Narciso Tomé’s spectacular Baroque masterpiece, El Transparente, floods the interior with heavenly light. The Chapel of the New Monarchs houses the tombs of Castilian royalty, a reminder that Toledo was once the beating heart of Spain’s political power. Among the cathedral’s greatest treasures is the Monstrance of Arfe, a dazzling Gothic creation of gilded silver and gold, encrusted with 260 figures and, according to tradition, fashioned partly from gold brought back by Columbus from the Americas. Every year during the Corpus Christi festival, this masterpiece takes center stage in a grand procession that fills the city with music, flowers, and pageantry.

Toledo Cathedral offers a vivid immersion into Spain’s past, where Roman stones, Islamic arches, Gothic vaults, and Renaissance splendor coexist under one magnificent roof. To step inside is to witness the centuries that forged both the city and the nation.

That project began in 1226, under the reign of King Ferdinand III, who envisioned a grand cathedral to symbolize the triumph of Christianity and the new power of Castile. For nearly two centuries, master architects, including Master Martín and the renowned Alonso de Covarrubias, labored to complete the vast structure. The result was one of the largest Gothic cathedrals in Europe, with five sweeping naves, a towering spire, and a façade adorned with ornate portals bearing names as dramatic as their sculptures: the Gate of Forgiveness, the Gate of the Last Judgment, and the ominous Gate of Hell. The building itself embodies Gothic grandeur, yet whispers of earlier civilizations remain embedded in its walls.

Inside, the cathedral unfolds as a treasury of Spanish art. The high altar rises like a forest of gilded wood and sculpted scenes from Christ’s Passion, while Narciso Tomé’s spectacular Baroque masterpiece, El Transparente, floods the interior with heavenly light. The Chapel of the New Monarchs houses the tombs of Castilian royalty, a reminder that Toledo was once the beating heart of Spain’s political power. Among the cathedral’s greatest treasures is the Monstrance of Arfe, a dazzling Gothic creation of gilded silver and gold, encrusted with 260 figures and, according to tradition, fashioned partly from gold brought back by Columbus from the Americas. Every year during the Corpus Christi festival, this masterpiece takes center stage in a grand procession that fills the city with music, flowers, and pageantry.

Toledo Cathedral offers a vivid immersion into Spain’s past, where Roman stones, Islamic arches, Gothic vaults, and Renaissance splendor coexist under one magnificent roof. To step inside is to witness the centuries that forged both the city and the nation.

5) Iglesia de El Salvador (Church of El Salvador)

The Church of El Salvador is a small yet exceptional church with a rich history. Completed in 1159, it was built on the site of four successive constructions, including a 9th-century Visigothic religious building, an 11th-century Taifa mosque, and a 12th-century Christian church. The church is still oriented southeast, towards Mecca, as it was originally a mosque.

The most distinctive element of the Church of El Salvadoris the Visigothic pilaster, which dates back to the end of the 6th century or beginning of the 7th century. This Paleochristian relic has intricate relief carvings and depicts four scenes from the life of Christ, including the Cure of the Blind, the Resurrection of Lazarus, the Samaritan and the Hemorroísa. Despite its face being scraped by the Muslims, the pilaster's great size and attitudes make it distinguishable.

Although the church suffered a fire in the 15th century, it underwent an important restoration commissioned by Álvarez de Toledo. New chapels, including the Gothic chapel of Santa Catalina, were added, and different processes of archaeological investigation were carried out in the last decade of its history. The excavation of the parochial patio, the recovery of the primitive wall covering of the tower, and the archaeological excavation of the gospel and central naves were all part of the restoration process.

The Iglesia de El Salvador is also mentioned in the famous Spanish novel, Lazarillo de Tormes, and is the site where Joanna of Castile ("the Mad") and the dramatist Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla were baptized. It is located near other notable churches, including the Churches of Santo Tomé and Convento de Santa Úrsula.

The Church of El Salvador is an exceptional example of the city's rich history and cultural diversity, with elements from Visigothic, Muslim, and Christian eras blended together in its unique architecture.

The most distinctive element of the Church of El Salvadoris the Visigothic pilaster, which dates back to the end of the 6th century or beginning of the 7th century. This Paleochristian relic has intricate relief carvings and depicts four scenes from the life of Christ, including the Cure of the Blind, the Resurrection of Lazarus, the Samaritan and the Hemorroísa. Despite its face being scraped by the Muslims, the pilaster's great size and attitudes make it distinguishable.

Although the church suffered a fire in the 15th century, it underwent an important restoration commissioned by Álvarez de Toledo. New chapels, including the Gothic chapel of Santa Catalina, were added, and different processes of archaeological investigation were carried out in the last decade of its history. The excavation of the parochial patio, the recovery of the primitive wall covering of the tower, and the archaeological excavation of the gospel and central naves were all part of the restoration process.

The Iglesia de El Salvador is also mentioned in the famous Spanish novel, Lazarillo de Tormes, and is the site where Joanna of Castile ("the Mad") and the dramatist Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla were baptized. It is located near other notable churches, including the Churches of Santo Tomé and Convento de Santa Úrsula.

The Church of El Salvador is an exceptional example of the city's rich history and cultural diversity, with elements from Visigothic, Muslim, and Christian eras blended together in its unique architecture.

6) Iglesia de Santo Tome (Church of Saint Thomas) (must see)

The Church of Saint Thomas sits in the heart of Toledo and holds nearly a millennium of history within its walls. Its origins go back to the aftermath of 1085, when King Alfonso VI of León reclaimed the city from Muslim rule. Instead of demolishing the mosque that already stood on the site, he consecrated it as a Christian church-a common practice in reconquered cities, where sacred spaces were repurposed rather than destroyed. By the 14th century, however, the building had fallen into disrepair. The task of restoring and expanding it fell to Ruiz de Toledo, Lord of Orgaz and then mayor of the city. A generous patron of the Church, Ruiz de Toledo commissioned a reconstruction in which the former minaret was transformed into a graceful Mudéjar-style bell tower, its brick patterns and horseshoe arches preserving a hint of the site’s Islamic past within a Christian setting.

The architecture of the church reveals Toledo’s distinctive cultural layering. The layout follows the Latin cross, with three naves, a barrel vault, and a polygonal apse. The side chapels display ornate Baroque altarpieces, while the main chapel combines Gothic structure with Mudéjar decoration, crowned by a dome shaped like the eight-pointed Islamic Rub el Hizb star. A 16th-century baptismal font survives, and a later 19th-century chapel houses The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, a moving canvas by Vicente Portaña.

Yet what truly draws visitors from around the world is El Greco’s celebrated masterpiece, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz. Commissioned in 1586 to honor Ruiz de Toledo, the painting dramatizes the miraculous moment when Saints Stephen and Augustine descended from heaven to lay the Count in his grave. El Greco inserted his own likeness and that of his young son into the crowd of mourners, blending personal presence with historical memory in a swirl of elongated figures and luminous color. The painting remains one of the defining works of European Mannerism and a testament to Toledo’s role as the adopted home of the Cretan-born artist.

Saint Thomas offers more than a church visit. It is a vivid page from Spain’s past, where Roman, Islamic, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque traditions all converge. Standing within its star-vaulted nave, you glimpse the city’s shifting identities-and the extraordinary artistry that has made Toledo a cultural treasure.

The architecture of the church reveals Toledo’s distinctive cultural layering. The layout follows the Latin cross, with three naves, a barrel vault, and a polygonal apse. The side chapels display ornate Baroque altarpieces, while the main chapel combines Gothic structure with Mudéjar decoration, crowned by a dome shaped like the eight-pointed Islamic Rub el Hizb star. A 16th-century baptismal font survives, and a later 19th-century chapel houses The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, a moving canvas by Vicente Portaña.

Yet what truly draws visitors from around the world is El Greco’s celebrated masterpiece, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz. Commissioned in 1586 to honor Ruiz de Toledo, the painting dramatizes the miraculous moment when Saints Stephen and Augustine descended from heaven to lay the Count in his grave. El Greco inserted his own likeness and that of his young son into the crowd of mourners, blending personal presence with historical memory in a swirl of elongated figures and luminous color. The painting remains one of the defining works of European Mannerism and a testament to Toledo’s role as the adopted home of the Cretan-born artist.

Saint Thomas offers more than a church visit. It is a vivid page from Spain’s past, where Roman, Islamic, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque traditions all converge. Standing within its star-vaulted nave, you glimpse the city’s shifting identities-and the extraordinary artistry that has made Toledo a cultural treasure.

7) Museo del Greco (El Greco Museum) (must see)

The El Greco Museum preserves the memory of one of Spain’s most distinctive painters, Domenikos Theotokopoulos, universally known as El Greco. Born in Crete and trained in Venice and Rome, he arrived in Spain in the 1570s. Toledo, then a thriving religious and cultural capital, became his permanent home. The city’s dramatic landscapes and spiritual atmosphere suited his bold artistic style, defined by elongated figures, vibrant colors, and an intensity that baffled many of his contemporaries but later influenced masters such as Picasso, Cézanne, and even modern expressionists.

The museum itself has an unusual history. Despite its name, El Greco never actually lived in the building. In the early 20th century, the Marquis of Vega-Inclán, a passionate patron of Spanish culture, purchased a cluster of houses in Toledo’s former Jewish quarter. With architect Eladio Laredo, he transformed them into a reconstruction of a 16th- and 17th-century residence reminiscent of where El Greco might have lived. This project was part of a broader effort by the Marquis to preserve Spain’s cultural heritage; he also created the Museum of Romanticism in Madrid and restored Cervantes’ house in Valladolid. The El Greco Museum opened its doors in 1911, bringing together many of the artist’s scattered works and later, in 1964, was officially designated the Museum of the Sephardic heritage as well, ensuring its protection under the state.

Inside, the museum houses more than 3,000 objects, from Talavera de la Reina ceramics to antique furnishings and beautifully decorated Moorish-style wooden ceilings, which reflect the city’s long history of cultural fusion. Yet the most dazzling treasures are El Greco’s own canvases. The museum preserves an extraordinary series of thirteen portraits of Christ and the Apostles, painted between 1610 and 1614, alongside masterpieces such as The Tears of Saint Peter and View and Plan of Toledo. Together, these works reveal the artist’s visionary approach, bridging Byzantine tradition with Renaissance and mannerist experimentation.

For visitors, the El Greco Museum is not only an art gallery but a time capsule of Toledo’s Golden Age. To explore its rooms and courtyards is to step into the world that inspired El Greco, where religion, art, and history intertwined to leave a legacy that still captivates travelers today.

The museum itself has an unusual history. Despite its name, El Greco never actually lived in the building. In the early 20th century, the Marquis of Vega-Inclán, a passionate patron of Spanish culture, purchased a cluster of houses in Toledo’s former Jewish quarter. With architect Eladio Laredo, he transformed them into a reconstruction of a 16th- and 17th-century residence reminiscent of where El Greco might have lived. This project was part of a broader effort by the Marquis to preserve Spain’s cultural heritage; he also created the Museum of Romanticism in Madrid and restored Cervantes’ house in Valladolid. The El Greco Museum opened its doors in 1911, bringing together many of the artist’s scattered works and later, in 1964, was officially designated the Museum of the Sephardic heritage as well, ensuring its protection under the state.

Inside, the museum houses more than 3,000 objects, from Talavera de la Reina ceramics to antique furnishings and beautifully decorated Moorish-style wooden ceilings, which reflect the city’s long history of cultural fusion. Yet the most dazzling treasures are El Greco’s own canvases. The museum preserves an extraordinary series of thirteen portraits of Christ and the Apostles, painted between 1610 and 1614, alongside masterpieces such as The Tears of Saint Peter and View and Plan of Toledo. Together, these works reveal the artist’s visionary approach, bridging Byzantine tradition with Renaissance and mannerist experimentation.

For visitors, the El Greco Museum is not only an art gallery but a time capsule of Toledo’s Golden Age. To explore its rooms and courtyards is to step into the world that inspired El Greco, where religion, art, and history intertwined to leave a legacy that still captivates travelers today.

8) Synagogue of El Transito and Sephardic Museum

The Synagogue of El Transito, officially known as the Synagogue of Samuel ha-Levi, is one of Toledo’s most intriguing historic survivors. Built in 1357, it was commissioned by Samuel ha-Levi Abulafia, the influential treasurer of King Pedro I of Castile, who spared no expense in creating a sanctuary worthy of both faith and prestige. The architect worked in the Mudéjar tradition, a style that wove Islamic decorative brilliance into non-Islamic buildings. The result is a monument that often surprises first-time visitors: its patterned brick walls, scalloped arches, and richly ornamented stucco resemble a mosque more than the synagogues many expect. Inside, four supporting columns divide the square plan into nine bays crowned by domes, the central one unfolding in the pattern of an eight-pointed star. The carved capitals, influenced by Byzantine and Corinthian forms, and the painted larchwood ceiling create an atmosphere of both delicacy and grandeur.

Toledo’s turbulent history left its marks on this building. When the city fell to King Alfonso VI in 1085, its mosques were gradually Christianized. El Transito followed the same fate after the Catholic Monarchs enforced the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. Renamed Saint Mary of the Assumption, it passed to the Order of Calatrava and later became a military barracks during the Napoleonic occupation. Restoration work in the 19th and 20th centuries saved its fragile details, and in 1877 it was recognized as a Spanish National Monument. By 1964, it had taken on a new life as the Sephardic Museum, preserving manuscripts, textiles, ritual objects, and the memory of Toledo’s Jewish community.

For today’s visitors, the Synagogue of El Transito offers more than decorative splendor. Within its arches and starry ceiling, one feels the pulse an enduring dialogue between three cultures that once flourished side by side.

Toledo’s turbulent history left its marks on this building. When the city fell to King Alfonso VI in 1085, its mosques were gradually Christianized. El Transito followed the same fate after the Catholic Monarchs enforced the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. Renamed Saint Mary of the Assumption, it passed to the Order of Calatrava and later became a military barracks during the Napoleonic occupation. Restoration work in the 19th and 20th centuries saved its fragile details, and in 1877 it was recognized as a Spanish National Monument. By 1964, it had taken on a new life as the Sephardic Museum, preserving manuscripts, textiles, ritual objects, and the memory of Toledo’s Jewish community.

For today’s visitors, the Synagogue of El Transito offers more than decorative splendor. Within its arches and starry ceiling, one feels the pulse an enduring dialogue between three cultures that once flourished side by side.

9) Sinagoga de Santa Maria La Blanca (Synagogue of Saint Mary the White)

The Synagogue of Saint Mary the White holds a unique place in Toledo’s history: built in 1180, it is often described as the oldest surviving synagogue in Europe. Its very name carries traces of the city’s multicultural past. While today it is known by a Christian dedication, the site was originally called Sinagoga Mayor and, before the Christian reconquest of Toledo, it stood beside the Blocked Gate, recalling the centuries when the city belonged to Al-Andalus. The synagogue itself was commissioned by ben Shoshan, a powerful Jewish court official under King Alfonso VIII, and constructed by Moorish artisans, resulting in an architectural language steeped in the Mudéjar style. With its graceful horseshoe arches, geometric stuccowork, and delicate brick patterns reminiscent of Córdoba’s Great Mosque, the building looks more like an Islamic sanctuary than a conventional synagogue.

Stepping inside, visitors are greeted by rows of whitewashed octagonal columns topped with capitals that blend Islamic, Corinthian, and Byzantine motifs. The prayer hall is arranged as a square divided into nine bays, its central vault forming an eight-pointed star. Once, the scallop-shell arch at the eastern wall framed the Torah ark, while adjoining spaces included a rabbinical house, courtyards, and a ritual bath, underscoring its role as a vital center of Jewish communal life.

Toledo’s shifting history, however, left its mark. In 1391 anti-Jewish riots devastated the community, and by 1405 the synagogue was converted into a church dedicated to Saint Mary the White under the Order of Calatrava. Renaissance chapels were added in the 16th century, and the building later served as a barracks. Painstaking 20th-century restoration revived its medieval splendor, allowing its intricate interiors to be admired once more.

For modern travelers, the Synagogue of Saint Mary the White offers a vivid lesson in cultural exchange, where Christian, Muslim, and Jewish traditions converge in stone, plaster, and light-an enduring testament to Toledo’s complex and layered past.

Stepping inside, visitors are greeted by rows of whitewashed octagonal columns topped with capitals that blend Islamic, Corinthian, and Byzantine motifs. The prayer hall is arranged as a square divided into nine bays, its central vault forming an eight-pointed star. Once, the scallop-shell arch at the eastern wall framed the Torah ark, while adjoining spaces included a rabbinical house, courtyards, and a ritual bath, underscoring its role as a vital center of Jewish communal life.

Toledo’s shifting history, however, left its mark. In 1391 anti-Jewish riots devastated the community, and by 1405 the synagogue was converted into a church dedicated to Saint Mary the White under the Order of Calatrava. Renaissance chapels were added in the 16th century, and the building later served as a barracks. Painstaking 20th-century restoration revived its medieval splendor, allowing its intricate interiors to be admired once more.

For modern travelers, the Synagogue of Saint Mary the White offers a vivid lesson in cultural exchange, where Christian, Muslim, and Jewish traditions converge in stone, plaster, and light-an enduring testament to Toledo’s complex and layered past.

10) Monasterio de San Juan de los Reyes (Monastery of Saint John of the Monarchs) (must see)

Saint John of the Monarchs doesn’t merely occupy a corner of Toledo’s Town Hall Square-it embodies the aspirations, triumphs, and scars of a city that once served as the heartbeat of Spain. Its story is tied to one of the most famous unions in European history: the 1469 marriage of Isabella of Castile, then only eighteen, and Ferdinand of Aragon, nineteen. That political and romantic alliance set the foundations for the unification of Spain, and in gratitude for their victory over King Afonso V of Portugal at the Battle of Toro in 1476, the Catholic Monarchs commissioned a new Franciscan monastery in Toledo the following year. They intended it to serve as both a spiritual offering and their future burial place.

The architect chosen, Juan Guas-master of the flamboyant Isabelline Gothic style-oversaw the project between 1477 and 1504. The result was a monumental complex, a Latin-cross church with three naves, a tall nave flanked by side chapels, and a polygonal chancel. Overhead, star-shaped ribbed vaults unfold like stone lacework, while the cloisters combine Gothic verticality with ornate carvings of saints, plants, and mythical beasts. Later additions in the 16th century included a Renaissance altarpiece by Felipe Bigarny and striking paintings of the Passion and Resurrection by Francisco de Comontes, which brought warmth and color to the otherwise austere interior.

The exterior makes an equally powerful statement. The façade is framed by two elegant towers capped with spires, while heavy chains dangle along the walls-grim relics taken from Christians once held captive by the Moors, now transformed into symbols of liberation after the Reconquista.

Though Ferdinand and Isabella were ultimately buried in Granada, their intended mausoleum in Toledo still stands as a testament to their ambition and their role in shaping a united Spain. Today, visitors who step into San Juan de los Reyes can feel the blend of history and devotion in every arch and courtyard. The monastery’s survival through wars, including the damage inflicted during the Napoleonic occupation of 1808 before its careful restoration in the 20th century, has only deepened its aura.

The monastery offers a rare chance to experience Spain’s history not through books or monuments alone, but within the very walls that once echoed with the footsteps of monarchs, friars, and the faithful.

The architect chosen, Juan Guas-master of the flamboyant Isabelline Gothic style-oversaw the project between 1477 and 1504. The result was a monumental complex, a Latin-cross church with three naves, a tall nave flanked by side chapels, and a polygonal chancel. Overhead, star-shaped ribbed vaults unfold like stone lacework, while the cloisters combine Gothic verticality with ornate carvings of saints, plants, and mythical beasts. Later additions in the 16th century included a Renaissance altarpiece by Felipe Bigarny and striking paintings of the Passion and Resurrection by Francisco de Comontes, which brought warmth and color to the otherwise austere interior.

The exterior makes an equally powerful statement. The façade is framed by two elegant towers capped with spires, while heavy chains dangle along the walls-grim relics taken from Christians once held captive by the Moors, now transformed into symbols of liberation after the Reconquista.

Though Ferdinand and Isabella were ultimately buried in Granada, their intended mausoleum in Toledo still stands as a testament to their ambition and their role in shaping a united Spain. Today, visitors who step into San Juan de los Reyes can feel the blend of history and devotion in every arch and courtyard. The monastery’s survival through wars, including the damage inflicted during the Napoleonic occupation of 1808 before its careful restoration in the 20th century, has only deepened its aura.

The monastery offers a rare chance to experience Spain’s history not through books or monuments alone, but within the very walls that once echoed with the footsteps of monarchs, friars, and the faithful.

11) Iglesia de San Ildefonso (Church of San Ildefonso)

The Church of San Ildefonso, also known as the Jesuit Church, is a magnificent example of the Baroque style located in Toledo. Situated in one of the highest points in the city, it offers a breathtaking panoramic view of Toledo from its towers. The church is dedicated to Saint Ildefonso of Toledo, the patron saint of the city and Father of the Church.

The construction of the church took more than a century to complete, with work starting in 1629 on lands acquired by the Jesuits of Toledo in 1569. The location had previously hosted the houses of Juan Hurtado de Mendoza Rojas y Guzmán, count of Orgaz, and was also the birthplace of Saint Ildefonsus. The approach followed the example of the Jesuit churches of Palencia and Alcalá de Henares, as well as the Church of the Gesù in Rome.

The church's enormous dimensions and great architecture are expressed in the single nave flanked by side chapels that communicate among themselves, as well as the great dome that covers the area of the transept. The facade and reredos are in Baroque style and were designed by Francisco Bautista, who replaced Jesuit architect Pedro Sánchez after his death in 1633. Bartolomé Zumbigo, a native architect of Toledo, completed the towers and facade.

San Ildefonso was consecrated in 1718, although the sacristy, the main chapel, and the octave were incomplete at the time. The temple was finally completed in 1765 under the direction of Jose Hernandez Sierra, an architect from Salamanca. Unfortunately for the Jesuits, the church was seized just two years later, along with all other Jesuit properties in Spain, under the charge of instigating the Esquilache Riots. The Company of Jesus did not recover the church until the twentieth century.

The Church of San Ildefonso is a superb example of the Baroque style and a testament to the counter-reformation spirituality that influenced its design. Its historical and architectural significance make it a must-see destination for visitors to Toledo.

The construction of the church took more than a century to complete, with work starting in 1629 on lands acquired by the Jesuits of Toledo in 1569. The location had previously hosted the houses of Juan Hurtado de Mendoza Rojas y Guzmán, count of Orgaz, and was also the birthplace of Saint Ildefonsus. The approach followed the example of the Jesuit churches of Palencia and Alcalá de Henares, as well as the Church of the Gesù in Rome.

The church's enormous dimensions and great architecture are expressed in the single nave flanked by side chapels that communicate among themselves, as well as the great dome that covers the area of the transept. The facade and reredos are in Baroque style and were designed by Francisco Bautista, who replaced Jesuit architect Pedro Sánchez after his death in 1633. Bartolomé Zumbigo, a native architect of Toledo, completed the towers and facade.

San Ildefonso was consecrated in 1718, although the sacristy, the main chapel, and the octave were incomplete at the time. The temple was finally completed in 1765 under the direction of Jose Hernandez Sierra, an architect from Salamanca. Unfortunately for the Jesuits, the church was seized just two years later, along with all other Jesuit properties in Spain, under the charge of instigating the Esquilache Riots. The Company of Jesus did not recover the church until the twentieth century.

The Church of San Ildefonso is a superb example of the Baroque style and a testament to the counter-reformation spirituality that influenced its design. Its historical and architectural significance make it a must-see destination for visitors to Toledo.

12) Convento de los Carmelitas Descalzos (Convent of the Discalced Carmelites)

The Convent of the Discalced Carmelites in Toledo is a stunning 17th-century monastery complex that boasts of an elaborate façade and intricate azulejo decoration. The complex was built between 1643 and 1655 according to the plans of the Discalced Carmelite, Fray Pedro de San Bartolomé. The building is arranged around a patio and features a rectangular floor plan with three naves, and a wide transept with short arms. The central nave is double-width and higher than the lateral ones.

The interior of the monastery is adorned with decorative plasterwork of free design, which is typical of the 16th century in Toledo. The vaults of the central nave, choir, and transept are half-barreled, and there are frescoes portraying biblical scenes. The monastery’s spacious nave and chapels are glazed with the azulejo ceramic panels that are typical of the region. The exterior of the building is made of exposed brick with masonry rafas and cubic volumes and rectilinear profiles.

The stone doorway is of the altarpiece-body and attic type, with a niche and Tuscan pilasters as its fundamental supports. The tower rising from the central portion of the façade is composed of exposed brick and features a rose window with a cross marking the pediment. The central façade also has a religious sculpture in the center and an arched portal beneath it.

The Convento de los Carmelitas Descalzos is not just a religious building but also serves as a hostel where travelers and pilgrims can lodge, dine, and take part in prayer ceremonies. The history of the convent is extensive, and it is believed that John of the Cross took refuge here following his imprisonment. The monastery was used as a Minor Seminary in the 1830s and was handed back to the convent towards the end of the 19th century. During the Spanish Civil War, many friars were killed in the monastery.

Visitors to the Convento de los Carmelitas Descalzos can enjoy the relaxing ambiance within the church and cool down here on hot summer days. The monastery is located towards the northern end of the city center and can be reached by bus or on foot from other parts of the historic zone. Visitors can also drive and leave their car in one of the spaces in front of the church.

The interior of the monastery is adorned with decorative plasterwork of free design, which is typical of the 16th century in Toledo. The vaults of the central nave, choir, and transept are half-barreled, and there are frescoes portraying biblical scenes. The monastery’s spacious nave and chapels are glazed with the azulejo ceramic panels that are typical of the region. The exterior of the building is made of exposed brick with masonry rafas and cubic volumes and rectilinear profiles.

The stone doorway is of the altarpiece-body and attic type, with a niche and Tuscan pilasters as its fundamental supports. The tower rising from the central portion of the façade is composed of exposed brick and features a rose window with a cross marking the pediment. The central façade also has a religious sculpture in the center and an arched portal beneath it.

The Convento de los Carmelitas Descalzos is not just a religious building but also serves as a hostel where travelers and pilgrims can lodge, dine, and take part in prayer ceremonies. The history of the convent is extensive, and it is believed that John of the Cross took refuge here following his imprisonment. The monastery was used as a Minor Seminary in the 1830s and was handed back to the convent towards the end of the 19th century. During the Spanish Civil War, many friars were killed in the monastery.

Visitors to the Convento de los Carmelitas Descalzos can enjoy the relaxing ambiance within the church and cool down here on hot summer days. The monastery is located towards the northern end of the city center and can be reached by bus or on foot from other parts of the historic zone. Visitors can also drive and leave their car in one of the spaces in front of the church.

13) Ermita "Mezquita" del Cristo de la Luz (Mosque of Cristo de la Luz)

The Mosque of Cristo de la Luz may be small-barely a square of 26 feet on each side-but it carries more than a millennium of history in its brick and stone. Built in 999 CE, when Toledo was under Muslim rule, it was originally known as the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, taking its name from the nearby “Blocked Gate.” Its founder, the wealthy courtier Ahmad ibn Ḥadīdī, employed an Moorish architect to design it. The latter left his name in an Arabic inscription on the façade, alongside a declaration that the patron hoped the building would secure him a place in paradise.

The design is a jewel of Mudéjar artistry shaped by Islamic tradition. Inside, four slender columns divide the space into nine bays, each crowned with a unique ribbed vault that creates a play of light and shadow. The arches are of the horseshoe type familiar from Córdoba, and one wall still preserves the mihrab, the niche indicating the direction of Mecca. In the 14th century, the original minaret was reworked into a bell tower, symbolizing the city’s shifting religious identity.

That transformation had begun centuries earlier: when King Alfonso VI of Castile retook Toledo in 1085, many mosques were converted into churches rather than destroyed. This one was dedicated to the Holy Cross, later acquiring the name “Christ of the Light” from a legend about King Alfonso’s horse kneeling to reveal a long-hidden statue of Saint Ildefonso.

Visitors are able to step into a serene hall where Mudéjar arches and Christian additions coexist. The effect is both scholarly and atmospheric, a vivid reminder of Toledo’s unique role as a meeting ground of civilizations.

The design is a jewel of Mudéjar artistry shaped by Islamic tradition. Inside, four slender columns divide the space into nine bays, each crowned with a unique ribbed vault that creates a play of light and shadow. The arches are of the horseshoe type familiar from Córdoba, and one wall still preserves the mihrab, the niche indicating the direction of Mecca. In the 14th century, the original minaret was reworked into a bell tower, symbolizing the city’s shifting religious identity.

That transformation had begun centuries earlier: when King Alfonso VI of Castile retook Toledo in 1085, many mosques were converted into churches rather than destroyed. This one was dedicated to the Holy Cross, later acquiring the name “Christ of the Light” from a legend about King Alfonso’s horse kneeling to reveal a long-hidden statue of Saint Ildefonso.

Visitors are able to step into a serene hall where Mudéjar arches and Christian additions coexist. The effect is both scholarly and atmospheric, a vivid reminder of Toledo’s unique role as a meeting ground of civilizations.

14) Puerta de Bisagra Nueva (New Hinged Door)

The New Hinged Door is a magnificent city gate located in Toledo. It is known as the "New Bisagra Gate" because of its proximity to the smaller "Old Hinge Gate" or "Alfonso VI Gate." This gate was the only direct access to the city of Toledo from the north. Its Muslim name was bab a Ssaqra or "Puerta de la Sagra."

There was some debate regarding its origin and antiquity, whether it was first Arab or Mudejar, but archaeological work has provided an answer. Excavation work carried out in 1999 documented that the Renaissance structure was built on an old elbow access. During the restoration project, various materials were unearthed that clearly dated the door before the conquest of the city by Alfonso VI in the year 1085. The powerful foundations and the angled structure underline the monumental character of the structure, which was likely sealed during the conquest of the city.

The gate is made up of two independent bodies with two high crenellated walls that join them, forming a patio between them. The external side is formed by a semicircular arch with padded ashlars, on which there is a large shield of the "Imperial City," with its double-headed eagle. This entrance is flanked by two large circular towers. The body that faces the city has another door with a semicircular arch, flanked by two square towers topped by pyramidal roofs. One of the towers located to the west was part of the original medieval structure, and its rope and brand rigging is still visible today.

There was some debate regarding its origin and antiquity, whether it was first Arab or Mudejar, but archaeological work has provided an answer. Excavation work carried out in 1999 documented that the Renaissance structure was built on an old elbow access. During the restoration project, various materials were unearthed that clearly dated the door before the conquest of the city by Alfonso VI in the year 1085. The powerful foundations and the angled structure underline the monumental character of the structure, which was likely sealed during the conquest of the city.

The gate is made up of two independent bodies with two high crenellated walls that join them, forming a patio between them. The external side is formed by a semicircular arch with padded ashlars, on which there is a large shield of the "Imperial City," with its double-headed eagle. This entrance is flanked by two large circular towers. The body that faces the city has another door with a semicircular arch, flanked by two square towers topped by pyramidal roofs. One of the towers located to the west was part of the original medieval structure, and its rope and brand rigging is still visible today.

15) Iglesia de Santiago del Arrabal (Church of Santiago)

The Church of Santiago is a remarkable example of Mudejar architecture. Built between 1245 and 1248 at the orders of Sancho II, the church is dedicated to Saint James and was constructed on the site of a previous building, possibly a mosque. Many features of Islamic architecture, including the characteristic horseshoe arches, can still be seen in the current building.

During its foundation, the Diosdado family, knight commanders of the Order of Santiago, were the patrons of the church. The church's tower dates back to the 12th century and has a square floor plan. The church itself, with three naves, a gabled roof, and a triple apse, was built in the 13th century under the patronage of Sancho Capelo, the king of Portugal.

The exterior of the church is adorned with a double row of multifoil openings, and it has three portals, framed by horseshoe arches. Inside, the church features a stunning 14th-century Mudejar plasterwork pulpit, as well as several tombstones and a beautiful Plateresque high reredos from the 16th century.

Today, the Iglesia de Santiago del Arrabal is considered one of the most striking Mudejar temples in Toledo, and its unique combination of Christian and Islamic architecture makes it an important attraction for visitors to the city.

During its foundation, the Diosdado family, knight commanders of the Order of Santiago, were the patrons of the church. The church's tower dates back to the 12th century and has a square floor plan. The church itself, with three naves, a gabled roof, and a triple apse, was built in the 13th century under the patronage of Sancho Capelo, the king of Portugal.

The exterior of the church is adorned with a double row of multifoil openings, and it has three portals, framed by horseshoe arches. Inside, the church features a stunning 14th-century Mudejar plasterwork pulpit, as well as several tombstones and a beautiful Plateresque high reredos from the 16th century.

Today, the Iglesia de Santiago del Arrabal is considered one of the most striking Mudejar temples in Toledo, and its unique combination of Christian and Islamic architecture makes it an important attraction for visitors to the city.

16) Puerta del Sol (Sun Gate)

The Sun Gate is one of Toledo’s most recognizable entrances, a structure that has watched centuries of travelers climb the steep slope toward the old city. Its name is thought to come either from a carved sun that once adorned its façade or from its orientation toward the rising sun in the east. The gate itself was built in the 14th century by the Knights Hospitaller, the military order founded in Jerusalem, who clearly wanted their handiwork to make a lasting impression.

Although the gate was part of Toledo’s defensive walls, it also drew on the city’s rich multicultural legacy. The design incorporates the graceful horseshoe arches of Islamic art, a style that remained influential long after Christian forces recaptured Toledo in 1085. The façade carries decorative brick patterns typical of Mudéjar architecture, while a central medallion shows Saint Ildefonso-Toledo’s patron saint-receiving his miraculous chasuble, framed by the radiant sun symbol that gave the gate its name.

For centuries, the square before the gate served as both marketplace and stage. Merchants and travelers once streamed through this entryway with caravans of goods, while heralds proclaimed royal decrees beneath its arch. It was a place where commerce, ritual, and civic life converged.

Today, the Sun Gate remains a favorite backdrop for photographs, its brick towers standing firm against the sky. Visitors who arrive here can pause to take in the view over the Tagus and imagine the countless generations who crossed this very threshold into Toledo’s historic heart.

Although the gate was part of Toledo’s defensive walls, it also drew on the city’s rich multicultural legacy. The design incorporates the graceful horseshoe arches of Islamic art, a style that remained influential long after Christian forces recaptured Toledo in 1085. The façade carries decorative brick patterns typical of Mudéjar architecture, while a central medallion shows Saint Ildefonso-Toledo’s patron saint-receiving his miraculous chasuble, framed by the radiant sun symbol that gave the gate its name.

For centuries, the square before the gate served as both marketplace and stage. Merchants and travelers once streamed through this entryway with caravans of goods, while heralds proclaimed royal decrees beneath its arch. It was a place where commerce, ritual, and civic life converged.

Today, the Sun Gate remains a favorite backdrop for photographs, its brick towers standing firm against the sky. Visitors who arrive here can pause to take in the view over the Tagus and imagine the countless generations who crossed this very threshold into Toledo’s historic heart.