Custom Walk in Munich, Germany by michellebasson_6583b created on 2025-07-28

Guide Location: Germany » Munich

Guide Type: Custom Walk

# of Sights: 12

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 5.5 Km or 3.4 Miles

Share Key: FJ6Y5

Guide Type: Custom Walk

# of Sights: 12

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 5.5 Km or 3.4 Miles

Share Key: FJ6Y5

How It Works

Please retrieve this walk in the GPSmyCity app. Once done, the app will guide you from one tour stop to the next as if you had a personal tour guide. If you created the walk on this website or come to the page via a link, please follow the instructions below to retrieve the walk in the app.

Retrieve This Walk in App

Step 1. Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" on Apple App Store or Google Play Store.

Step 2. In the GPSmyCity app, download(or launch) the guide "Munich Map and Walking Tours".

Step 3. Tap the menu button located at upper right corner of the "Walks" screen and select "Retrieve custom walk". Enter the share key: FJ6Y5

1) Isartor

This Gothic building used to be one of the four primary gates of the medieval city wall. It served as a defensive fortification and is the easternmost of Munich's three remaining Gothic town gates (Isartor, Sendlinger Tor, and Karlstor). The gate, known as "Tor," is situated near the Isar River and derives its name from it. The Isartor was constructed in 1337 as part of Munich's expansion and the building of the second city wall, which took place between 1285 and 1337 under the rule of Emperor Louis IV.

Today, the Isartor is the sole surviving medieval gate in Munich that has preserved its central main tower, and the restoration work carried out by Friedrich von Gärtner in 1833-35 has faithfully reproduced its original dimensions and appearance. The frescoes, created in 1835 by Bernhard von Neher, depict Emperor Louis's triumphant return after the Battle of Mühldorf in 1322. Presently, the Isartor houses a museum dedicated to the comedian and actor Karl Valentin, known for his humor. Additionally, there is a café within the premises for visitors to enjoy.

Today, the Isartor is the sole surviving medieval gate in Munich that has preserved its central main tower, and the restoration work carried out by Friedrich von Gärtner in 1833-35 has faithfully reproduced its original dimensions and appearance. The frescoes, created in 1835 by Bernhard von Neher, depict Emperor Louis's triumphant return after the Battle of Mühldorf in 1322. Presently, the Isartor houses a museum dedicated to the comedian and actor Karl Valentin, known for his humor. Additionally, there is a café within the premises for visitors to enjoy.

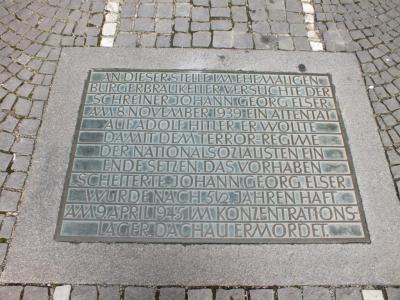

2) Bürgerbräukeller

The Bürgerbräukeller was a renowned beer establishment in Munich, inaugurated in 1885. It was initially part of the Bürgerliches Brauhaus operations, which later became part of Löwenbräu following a merger in 1921. This venue is historically notable for being the site where Hitler initiated the Beer Hall Putsch and the location of a failed assassination plot against him and other Nazi officials by Georg Elser in 1939.

From 1920 until 1923, this venue was pivotal for Nazi Party assemblies and witnessed Hitler's putsch commencement on November 8, 1923. After Hitler came to power, he observed the putsch's anniversary annually with a speech at this hall, followed by a commemorative march the next day, culminating in a homage to the putsch's fallen participants at the Feldherrnhalle.

A bomb, planted by Elser in a bid to kill Hitler during his annual speech in 1939, went off prematurely, avoiding Hitler but resulting in casualties and injuries. Elser faced years of imprisonment and was ultimately executed near World War II's end.

The Bürgerbräukeller endured significant damage due to the bombing and was later replaced as the putsch commemoration site by other venues during World War II. The building was eventually demolished in 1979 to make way for urban development, which now includes the GEMA headquarters, a cultural center, and a hotel. A memorial plaque at the GEMA building entrance indicates the historical location of Elser's bomb.

From 1920 until 1923, this venue was pivotal for Nazi Party assemblies and witnessed Hitler's putsch commencement on November 8, 1923. After Hitler came to power, he observed the putsch's anniversary annually with a speech at this hall, followed by a commemorative march the next day, culminating in a homage to the putsch's fallen participants at the Feldherrnhalle.

A bomb, planted by Elser in a bid to kill Hitler during his annual speech in 1939, went off prematurely, avoiding Hitler but resulting in casualties and injuries. Elser faced years of imprisonment and was ultimately executed near World War II's end.

The Bürgerbräukeller endured significant damage due to the bombing and was later replaced as the putsch commemoration site by other venues during World War II. The building was eventually demolished in 1979 to make way for urban development, which now includes the GEMA headquarters, a cultural center, and a hotel. A memorial plaque at the GEMA building entrance indicates the historical location of Elser's bomb.

3) Hitler's Early Residence in Munich

Adolf Hitler’s early residence in Munich played a significant role during the years when his political influence was taking shape. From May 1920 to October 1929, he lived in this third-floor flat-a period that saw him rise from fringe agitator to leader of the Nazi Party.

The building itself was well-situated: close enough to major meeting halls, yet far enough removed to offer a degree of privacy. During this time, Hitler wasn’t just living-he was strategizing. He worked on his autobiography, “My Struggle”, hosted party loyalists, and slowly built the organizational backbone of National Socialism from this very spot.

In the late 1920s, his half-niece, Geli Raubal, moved in. Their close and controversial relationship became the subject of intense speculation, ending in tragedy when Geli took her own life in 1931, after moving out. Her death left a lasting mark on Hitler.

After he relocated in 1929, the apartment faded into anonymity. Today, the building still stands, serving as a regular residential address with no plaque, no signage, no public trace of what once took place behind its doors. A quiet relic of a deeply consequential chapter.

The building itself was well-situated: close enough to major meeting halls, yet far enough removed to offer a degree of privacy. During this time, Hitler wasn’t just living-he was strategizing. He worked on his autobiography, “My Struggle”, hosted party loyalists, and slowly built the organizational backbone of National Socialism from this very spot.

In the late 1920s, his half-niece, Geli Raubal, moved in. Their close and controversial relationship became the subject of intense speculation, ending in tragedy when Geli took her own life in 1931, after moving out. Her death left a lasting mark on Hitler.

After he relocated in 1929, the apartment faded into anonymity. Today, the building still stands, serving as a regular residential address with no plaque, no signage, no public trace of what once took place behind its doors. A quiet relic of a deeply consequential chapter.

4) Hofgarten and War Memorial

The Hofgarten is a peaceful, geometrically designed retreat-and one of the largest Mannerist gardens to be found north of the Alps. Originally laid out in the early 1600s, it is arranged around two straight main paths that cross at right angles. At their intersection stands the Temple of Diana, an elegant polygonal pavilion crowned with a bronze figure representing Bavaria. Lining the edges of the garden are arcades that now house art galleries and cafés, their walls adorned with frescoes depicting historic moments from the Wittelsbach dynasty.

True to its 17th-century roots, the Hofgarten has been thoughtfully restored, with chestnut trees, flowerbeds, and fountains arranged just as the original plans intended. Tucked into the northeast corner is a striking black granite monument honoring the White Rose group-a circle of philosophy students who dared to resist the Nazi regime through non-violent means. After an unjust trial, they were executed, but their legacy lives on here in quiet remembrance. The garden also finds mention in T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”, widely regarded as one of the most important English-language poems of the 20th century. In the poem, it serves a symbol of fading aristocracy and the spiritual emptiness that followed Europe’s royal decline.

At the eastern edge of the grounds, you’ll come across another poignant tribute-a memorial to Munich’s fallen from World War I. Within a rectangular enclosure lies an open crypt holding the statue of a fallen soldier. Inaugurated in 1924 by Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, the monument has since been recognized as a cultural landmark.

True to its 17th-century roots, the Hofgarten has been thoughtfully restored, with chestnut trees, flowerbeds, and fountains arranged just as the original plans intended. Tucked into the northeast corner is a striking black granite monument honoring the White Rose group-a circle of philosophy students who dared to resist the Nazi regime through non-violent means. After an unjust trial, they were executed, but their legacy lives on here in quiet remembrance. The garden also finds mention in T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”, widely regarded as one of the most important English-language poems of the 20th century. In the poem, it serves a symbol of fading aristocracy and the spiritual emptiness that followed Europe’s royal decline.

At the eastern edge of the grounds, you’ll come across another poignant tribute-a memorial to Munich’s fallen from World War I. Within a rectangular enclosure lies an open crypt holding the statue of a fallen soldier. Inaugurated in 1924 by Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, the monument has since been recognized as a cultural landmark.

5) Odeonsplatz

The Odeonsplatz is a significant square in Munich's heart, created in the early 19th century by architect Leo von Klenze. It marks the end of Ludwigstraße, a grand street designed concurrently. The square gets its name from a concert hall called the Odeon situated on its northwest side. Over time, the term "Odeonsplatz" has also come to describe the open area in front of the Residenz palace, bounded by the Theatine Church and the Feldherrnhalle, a monumental loggia to the south.

Situated to the north of Munich's historic center, Odeonsplatz borders two districts: Altstadt-Lehel to the east and Maxvorstadt to the west. Along the west side, set back from Ludwigstraße, stand the Odeon building and the Palais Leuchtenberg, both inspired by Rome's Palazzo Farnese. To the east is Klenze's commercial arcade with Café Tambosi included. A street runs between the western buildings toward the Palais Ludwig Ferdinand, leading also to Wittelsbacherplatz, another square Klenze designed.

The Feldherrnhalle at the square's edge is modeled on Florence's Loggia dei Lanzi. Odeonsplatz is accessible by its U-Bahn station and a bus line that connects to various museums. In 1972, it became part of Munich's pedestrian-only zone.

Historically, Odeonsplatz has been central to various public ceremonies, from funeral marches to victory parades, moving along Ludwigstraße to the Feldherrnhalle, with a special viewing stand by Ludwig I's statue. The path from Odeonsplatz to the annual Oktoberfest parade has remained unchanged for years.

Situated to the north of Munich's historic center, Odeonsplatz borders two districts: Altstadt-Lehel to the east and Maxvorstadt to the west. Along the west side, set back from Ludwigstraße, stand the Odeon building and the Palais Leuchtenberg, both inspired by Rome's Palazzo Farnese. To the east is Klenze's commercial arcade with Café Tambosi included. A street runs between the western buildings toward the Palais Ludwig Ferdinand, leading also to Wittelsbacherplatz, another square Klenze designed.

The Feldherrnhalle at the square's edge is modeled on Florence's Loggia dei Lanzi. Odeonsplatz is accessible by its U-Bahn station and a bus line that connects to various museums. In 1972, it became part of Munich's pedestrian-only zone.

Historically, Odeonsplatz has been central to various public ceremonies, from funeral marches to victory parades, moving along Ludwigstraße to the Feldherrnhalle, with a special viewing stand by Ludwig I's statue. The path from Odeonsplatz to the annual Oktoberfest parade has remained unchanged for years.

6) Feldherrnhalle (Field Marshall’s Hall)

The Field Marshal's Hall is a grand open-air loggia built to honor Bavaria’s military leaders and the soldiers who died in the Franco-Prussian War. Commissioned by King Ludwig I in the 1840s, it was constructed on the site of a former city gate. The design was inspired by Florence’s famous Loggia dei Lanzi, bringing a touch of Italian grandeur to Munich’s historic center.

Standing at the front are two imposing bronze statues commemorating key figures in Bavarian military history: Count Tilly, who played a major role during the Thirty Years’ War, and Count von Wrede, a marshal from the Napoleonic era. In 1882, a third sculpture was added at the center-this one celebrating the Bavarian army’s role in the Franco-Prussian War. As you approach, you’ll also spot two lion statues at the steps, crafted in 1906. One, mouth open, faces the Residenz Royal Palace; the other, with mouth closed, looks toward the nearby church.

Yet for many, the site is remembered most for the dramatic events of 1923. That year, during the failed Beer Hall Putsch, Adolf Hitler led around 2,000 followers in an attempted coup, marching toward the center of Munich in what he called a “people’s revolution.” They were met by the Bavarian police in front of this very loggia. A deadly confrontation followed-four officers and sixteen insurgents were killed. Hitler was arrested shortly after and imprisoned. A decade later, after coming to power, he elevated the failed revolt into a cornerstone of the Nazi cult.

Standing at the front are two imposing bronze statues commemorating key figures in Bavarian military history: Count Tilly, who played a major role during the Thirty Years’ War, and Count von Wrede, a marshal from the Napoleonic era. In 1882, a third sculpture was added at the center-this one celebrating the Bavarian army’s role in the Franco-Prussian War. As you approach, you’ll also spot two lion statues at the steps, crafted in 1906. One, mouth open, faces the Residenz Royal Palace; the other, with mouth closed, looks toward the nearby church.

Yet for many, the site is remembered most for the dramatic events of 1923. That year, during the failed Beer Hall Putsch, Adolf Hitler led around 2,000 followers in an attempted coup, marching toward the center of Munich in what he called a “people’s revolution.” They were met by the Bavarian police in front of this very loggia. A deadly confrontation followed-four officers and sixteen insurgents were killed. Hitler was arrested shortly after and imprisoned. A decade later, after coming to power, he elevated the failed revolt into a cornerstone of the Nazi cult.

7) Hofbrauhaus Beer Hall (must see)

Arguably the most famous ‘watering hole’ in Munich, this spot is the embodiment of Bavarian tradition and spirit. Its story began in 1589, founded as part of the Royal Brewery by Wilhelm V. Back then, it wasn’t even open to the public-reserved instead for royal use. That changed in 1828, when the doors were finally thrown open to everyone. Today, it's among the city’s most beloved gathering places, steeped in old-world charm.

On the ground floor, long tables fill the hall that can hold 1,000 drinkers while bands belt out folk tunes. The menu is full of Bavarian classics, and the atmosphere is pure celebration. Upstairs, a vaulted ceremonial hall can seat another 1,300 people, with additional side rooms for smaller gatherings. And when the weather’s warm, the beer garden becomes a favorite hangout-with its shady chestnut trees, bubbling fountain, and relaxed outdoor vibe. On a typical day, around 10,000 liters of beer are served here-that’s over 17,000 pints.

True to tradition, the beer follows the Bavarian Beer Purity Law of 1516, which allows only natural ingredients. That standard is still upheld across the city, and the brews here are no exception-crafted with care and full of flavor.

But not all of the building’s history is festive. On February 24, 1920, Adolf Hitler stood here to announce the official program of the then-fledgling Nazi Party. Just over a year later, on July 29, 1921, he was elected as the Party’s leader-right in this very hall. So while the beer house is rightly remembered for joy, music, and beer, it also witnessed one of the more sobering moments of 20th-century history.

On the ground floor, long tables fill the hall that can hold 1,000 drinkers while bands belt out folk tunes. The menu is full of Bavarian classics, and the atmosphere is pure celebration. Upstairs, a vaulted ceremonial hall can seat another 1,300 people, with additional side rooms for smaller gatherings. And when the weather’s warm, the beer garden becomes a favorite hangout-with its shady chestnut trees, bubbling fountain, and relaxed outdoor vibe. On a typical day, around 10,000 liters of beer are served here-that’s over 17,000 pints.

True to tradition, the beer follows the Bavarian Beer Purity Law of 1516, which allows only natural ingredients. That standard is still upheld across the city, and the brews here are no exception-crafted with care and full of flavor.

But not all of the building’s history is festive. On February 24, 1920, Adolf Hitler stood here to announce the official program of the then-fledgling Nazi Party. Just over a year later, on July 29, 1921, he was elected as the Party’s leader-right in this very hall. So while the beer house is rightly remembered for joy, music, and beer, it also witnessed one of the more sobering moments of 20th-century history.

8) Altes Rathaus (Old Town Hall)

Before the New Town Hall took over in 1874, the Old Town Hall was where Munich’s city government did its business. Unlike many buildings that were torn down to make way for the new structure, this one remained-preserved as a testament to the city’s commitment to restoration over replacement.

With its dove-grey façade, amber-tiled steeple, and delicate Gothic spires, the Hall captures the essence of its 15th-century origins-though what stands today isn’t an exact replica. Over time, additions like a baroque onion dome and later, an overly enthusiastic attempt at “regothification,” took the structure further from its medieval roots than what the current version reflects. Ironically, the faithful postwar reconstruction you see today may be closer to the spirit of the original than what existed before the Allied bombing.

The oldest surviving element is the 12th-century tower, once part of the city’s medieval fortifications. Today, it houses the Toy Museum, where you’ll find a charming collection of vintage toys-from antique train sets to miniature zoos-spread across four narrow floors connected by a spiral staircase. There's also a gift shop with hand-picked items that make for great souvenirs.

The ceremonial hall still retains its Gothic grandeur, with broad wooden barrel vaults and a frieze of 96 coats of arms lining one wall. Meanwhile, on the building’s side, there's a whimsical surprise: a bronze statue of Shakespeare’s Juliet, a gift from the city of Verona in the 1970s.

But the building also carries a darker legacy. In 1938, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels delivered a speech here that triggered the “Night of Broken Glass.” That night of terror saw synagogues burned, Jewish businesses destroyed, and thousands arrested. It’s widely seen as the moment when Nazi anti-Semitic violence escalated into what became the Holocaust.

With its dove-grey façade, amber-tiled steeple, and delicate Gothic spires, the Hall captures the essence of its 15th-century origins-though what stands today isn’t an exact replica. Over time, additions like a baroque onion dome and later, an overly enthusiastic attempt at “regothification,” took the structure further from its medieval roots than what the current version reflects. Ironically, the faithful postwar reconstruction you see today may be closer to the spirit of the original than what existed before the Allied bombing.

The oldest surviving element is the 12th-century tower, once part of the city’s medieval fortifications. Today, it houses the Toy Museum, where you’ll find a charming collection of vintage toys-from antique train sets to miniature zoos-spread across four narrow floors connected by a spiral staircase. There's also a gift shop with hand-picked items that make for great souvenirs.

The ceremonial hall still retains its Gothic grandeur, with broad wooden barrel vaults and a frieze of 96 coats of arms lining one wall. Meanwhile, on the building’s side, there's a whimsical surprise: a bronze statue of Shakespeare’s Juliet, a gift from the city of Verona in the 1970s.

But the building also carries a darker legacy. In 1938, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels delivered a speech here that triggered the “Night of Broken Glass.” That night of terror saw synagogues burned, Jewish businesses destroyed, and thousands arrested. It’s widely seen as the moment when Nazi anti-Semitic violence escalated into what became the Holocaust.

9) Peterskirche (St. Peter's Church) (must see)

Saint Peter’s Church rises from the highest point of Munich’s Old Town and holds the title of the city’s oldest public building. It played a key role in the city’s early development, with roots reaching back to the 12th century. In fact, the church was once part of the original monastery that gave the city its name-“ménchen” meaning “monks.” After the first structure was lost to fire, a new Gothic-style design took its place in the 13th century. Over time, the church evolved even further, getting a Baroque facelift in the 17th century and then a Rococo reimagining in the 18th. After World War II, major restoration work was carried out to return it to its former glory.

Step inside today, and you're met with an unexpectedly lavish interior. The high altar features a commanding statue of Saint Peter, surrounded by the Church Fathers, while the choir displays five intricately carved scenes from Peter’s life. Look closely and you may even spot the jeweled remains of Saint Mundita-an ornate, if somewhat haunting, presence.

The church’s tower, known as “Old Peter,” is another highlight. Equipped with eight clocks, seven bells, and a viewing gallery, it offers panoramic views over the city-and on clear days, even as far as the Alps. A set of color-coded markers on the lower platform helps gauge visibility; if you spot a white circle, it means you’re in luck. Climbing to the top is well worth the price, but be warned: it’s a steep ascent and not ideal for anyone with a fear of heights. For those who make it, two binocular viewers let you take in the rooftops, church spires, and skyline in vivid detail. And if you arrive before noon, you’ll get an unbeatable vantage point for watching the carillon perform over at Mary’s Square.

Step inside today, and you're met with an unexpectedly lavish interior. The high altar features a commanding statue of Saint Peter, surrounded by the Church Fathers, while the choir displays five intricately carved scenes from Peter’s life. Look closely and you may even spot the jeweled remains of Saint Mundita-an ornate, if somewhat haunting, presence.

The church’s tower, known as “Old Peter,” is another highlight. Equipped with eight clocks, seven bells, and a viewing gallery, it offers panoramic views over the city-and on clear days, even as far as the Alps. A set of color-coded markers on the lower platform helps gauge visibility; if you spot a white circle, it means you’re in luck. Climbing to the top is well worth the price, but be warned: it’s a steep ascent and not ideal for anyone with a fear of heights. For those who make it, two binocular viewers let you take in the rooftops, church spires, and skyline in vivid detail. And if you arrive before noon, you’ll get an unbeatable vantage point for watching the carillon perform over at Mary’s Square.

10) Marienplatz (Mary's Square) (must see)

Right in the center of Munich lies Mary’s Square, the city’s lively, historic core. Established back in 1158, it started out as a busy marketplace and a stage for medieval tournaments and public events. These days, it’s still the place where everything seems to converge-a perfect starting point for anyone exploring the city. Grand buildings rise on all sides, cafés spill onto the streets, and the square hums with energy from morning until night.

The star attraction is the New Town Hall, an elaborate neo-Gothic masterpiece brimming with stone figures, ornate carvings, and the famous Glockenspiel. At 11 a.m., noon, and again at 5 p.m. during the warmer months, the Glockenspiel puts on its quirky performance. Thirty-two mechanical figures spin into action, reenacting Bavarian legends to a soundtrack of bells and music. It’s theatrical, a little over-the-top, and completely delightful.

Across the square, you’ll also find the Old Town Hall, with its storybook tower and a toy museum tucked inside-great if you’re traveling with kids or just enjoy a touch of childhood nostalgia. Meanwhile in the center stands the Column of Saint Mary, raised in 1638 to mark the end of Swedish occupation during the Thirty Years' War. A gilded statue of the Virgin crowns the column-a quiet symbol in a bustling space, and the inspiration for the square’s name.

Street musicians, traditional restaurants, souvenir stalls-there’s always something happening around you. Want to shop? Stroll down Kaufinger Street, one of Munich’s busiest pedestrian avenues. If you’re more in the mood for architecture, the city’s Cathedral, with its distinctive twin domes, is just around the corner.

In short, Mary’s Square offers the perfect snapshot of Munich. Don’t rush through it-it’s a place to linger, look up, and let the city reveal itself one detail at a time.

The star attraction is the New Town Hall, an elaborate neo-Gothic masterpiece brimming with stone figures, ornate carvings, and the famous Glockenspiel. At 11 a.m., noon, and again at 5 p.m. during the warmer months, the Glockenspiel puts on its quirky performance. Thirty-two mechanical figures spin into action, reenacting Bavarian legends to a soundtrack of bells and music. It’s theatrical, a little over-the-top, and completely delightful.

Across the square, you’ll also find the Old Town Hall, with its storybook tower and a toy museum tucked inside-great if you’re traveling with kids or just enjoy a touch of childhood nostalgia. Meanwhile in the center stands the Column of Saint Mary, raised in 1638 to mark the end of Swedish occupation during the Thirty Years' War. A gilded statue of the Virgin crowns the column-a quiet symbol in a bustling space, and the inspiration for the square’s name.

Street musicians, traditional restaurants, souvenir stalls-there’s always something happening around you. Want to shop? Stroll down Kaufinger Street, one of Munich’s busiest pedestrian avenues. If you’re more in the mood for architecture, the city’s Cathedral, with its distinctive twin domes, is just around the corner.

In short, Mary’s Square offers the perfect snapshot of Munich. Don’t rush through it-it’s a place to linger, look up, and let the city reveal itself one detail at a time.

11) Neues Rathaus (New Town Hall) (must see)

In the second half of the 19th century, as Munich was growing rapidly and riding a wave of prosperity, city leaders decided they needed a new home for local government. The Old Town Hall had simply outgrown its purpose. They chose a prominent spot on the south side of Mary’s Square, cleared out around two dozen houses, and set the stage for something grand. Construction began in 1867 and continued all the way to 1909. Overseeing the project was a remarkably young architect-Georg Hauberrisser-just 24 when he started.

What emerged is a prime example of German pseudo-historical architecture-mock-Netherlands Gothic, to be exact. The building features six courtyards and a small garden at the back. Its façade is covered in intricate sculptures that reference Bavarian legends, local saints, and allegorical figures. At the top of the steeple stands a bronze statue of the “Munich Child,” the city’s traditional symbol. The tower also houses the fourth-largest chiming clock in Europe.

Every day, 43 bells ring out as copper figures dance in two scenes: a knightly tournament honoring the wedding of Duke Wilhelm V and Renata of Lorraine, and the legendary “Dance of the Coopers.” That dance, by the way, is still performed in the streets every seven years during Carnival to commemorate the passing of a plague epidemic in the early 1500s. Legend has it that coopers, loyal to the Duke, danced through the streets to inspire courage during tough times. The official dance moves were defined as far back as 1871.

The full carillon performance plays at 11 a.m., noon, and 5 p.m. in the summer, lasting up to 15 minutes depending on the day’s tune. As a whimsical finale, a tiny golden rooster perched above the clock lets out three soft chirps. And when evening falls, figures of a night watchman and the Angel of Peace appear in the upper windows, quietly blessing the “Munich Child” and the city below.

Visitors can ride the elevator to the viewing platform for sweeping views of the city. And beneath the building, the historic Ratskeller restaurant offers not just a good meal, but a truly atmospheric dining experience.

What emerged is a prime example of German pseudo-historical architecture-mock-Netherlands Gothic, to be exact. The building features six courtyards and a small garden at the back. Its façade is covered in intricate sculptures that reference Bavarian legends, local saints, and allegorical figures. At the top of the steeple stands a bronze statue of the “Munich Child,” the city’s traditional symbol. The tower also houses the fourth-largest chiming clock in Europe.

Every day, 43 bells ring out as copper figures dance in two scenes: a knightly tournament honoring the wedding of Duke Wilhelm V and Renata of Lorraine, and the legendary “Dance of the Coopers.” That dance, by the way, is still performed in the streets every seven years during Carnival to commemorate the passing of a plague epidemic in the early 1500s. Legend has it that coopers, loyal to the Duke, danced through the streets to inspire courage during tough times. The official dance moves were defined as far back as 1871.

The full carillon performance plays at 11 a.m., noon, and 5 p.m. in the summer, lasting up to 15 minutes depending on the day’s tune. As a whimsical finale, a tiny golden rooster perched above the clock lets out three soft chirps. And when evening falls, figures of a night watchman and the Angel of Peace appear in the upper windows, quietly blessing the “Munich Child” and the city below.

Visitors can ride the elevator to the viewing platform for sweeping views of the city. And beneath the building, the historic Ratskeller restaurant offers not just a good meal, but a truly atmospheric dining experience.

12) Karlsplatz (Karl's Square)

In 1791, after the city’s old fortifications were demolished on the orders of Elector of Bavaria Karl Theodor, a wide-open square was created on the western edge of Munich’s Old Town. Second only to Mary’s Square in size, it was officially named Karl’s Square in honor of the ruler-and the nearby gate took on the name Karl’s Gate. Locals, meanwhile, had another name in mind for this space; they called it Stachus, a nickname that stuck and is still widely used today. The name comes from a popular inn that stood on the corner of the square since the 1750s.

More recently, in 1902, architect Gabriel von Seidl added two elegant wings to the Karl's Gate, known as the Rondel Buildings. These Neo-Baroque structures feature two prominent towers and ground-floor arcades lined with shops-an early nod to the area’s commercial appeal.

Fast forward to the 1970s, and you’ll find a large circular fountain, now a favorite meeting spot for both locals and visitors. It’s also a great place to take a break, especially on warm summer afternoons. On the west side stands Kaufhof, Munich’s very first postwar department store. Meanwhile, beneath the surface, an entire network of underground shops spreads out from the U-Bahn and S-Bahn exits, making this one of the city’s busiest retail intersections.

All in all, Karl's Square isn’t just a square-it’s a crossroads of history, shopping, transport, and local life. And if you’re catching a tram, chances are you’ll pass through here-it’s one of the key hubs of Munich’s streetcar network.

More recently, in 1902, architect Gabriel von Seidl added two elegant wings to the Karl's Gate, known as the Rondel Buildings. These Neo-Baroque structures feature two prominent towers and ground-floor arcades lined with shops-an early nod to the area’s commercial appeal.

Fast forward to the 1970s, and you’ll find a large circular fountain, now a favorite meeting spot for both locals and visitors. It’s also a great place to take a break, especially on warm summer afternoons. On the west side stands Kaufhof, Munich’s very first postwar department store. Meanwhile, beneath the surface, an entire network of underground shops spreads out from the U-Bahn and S-Bahn exits, making this one of the city’s busiest retail intersections.

All in all, Karl's Square isn’t just a square-it’s a crossroads of history, shopping, transport, and local life. And if you’re catching a tram, chances are you’ll pass through here-it’s one of the key hubs of Munich’s streetcar network.