Minsk's Historical Churches Tour (Self Guided), Minsk

The religious life of Belarus has been strongly influenced by both the Orthodox and Catholic religions. Consequently, Minsk features several beautiful churches that are well worth your time and energy while in this fine city. Take a walk down Minsk religious sights today!

How it works: Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" from Apple App Store or Google Play Store to your mobile phone or tablet. The app turns your mobile device into a personal tour guide and its built-in GPS navigation functions guide you from one tour stop to next. The app works offline, so no data plan is needed when traveling abroad.

Minsk's Historical Churches Tour Map

Guide Name: Minsk's Historical Churches Tour

Guide Location: Belarus » Minsk (See other walking tours in Minsk)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 8

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 6.7 Km or 4.2 Miles

Author: Linda

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

Guide Location: Belarus » Minsk (See other walking tours in Minsk)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 8

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 6.7 Km or 4.2 Miles

Author: Linda

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

- Church of Saints Simon and Helen

- Cathedral of St. Apostles Peter and Paul

- Cathedral of Saint Virgin Mary

- Saint Joseph Church

- Cathedral of Holy Spirit

- Church of St. Mary Magdalena

- Church of Holy Trinity

- Church of Alexander Nevsky

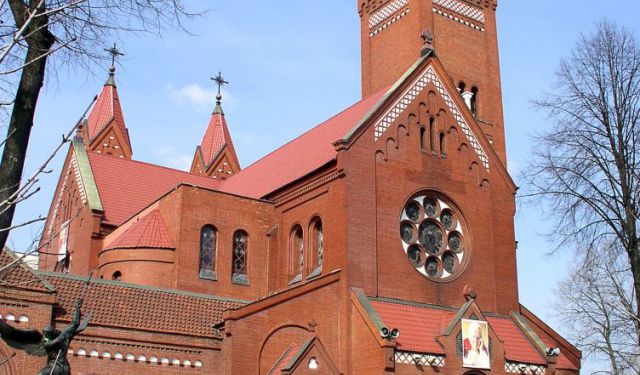

1) Church of Saints Simon and Helen (must see)

The Church of Saints Simon and Helen, commonly known as the Red Church, stands as one of Minsk’s most recognizable landmarks and a powerful symbol of Belarusian spiritual endurance. Located on Independence Square, it was built between 1905 and 1910 through the efforts of Edward Woyniłłowicz, a wealthy local nobleman, in memory of his children, Simon and Helen, who had passed away at a young age. Designed by Polish architects Tomasz Pajzderski and Władysław Marconi, the church’s striking red brick construction and neo-Romanesque design marked a dramatic contrast to the city’s largely neoclassical surroundings.

Beyond its architectural charm, the Red Church carries a layered and often tragic history. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, it was seized by Soviet authorities and transformed into a theater and later a film studio—its religious role completely suppressed. It was not until the late 20th century, during Belarus’s national awakening, that the church was restored to the Roman Catholic community, becoming once again a place of worship and a focal point of local identity.

Inside, visitors will find a serene interior defined by stained-glass windows, symbolic murals, and a calm atmosphere that contrasts the bustle of Independence Square outside. The surrounding grounds host memorials to those who perished during wars and political repressions, reinforcing the church’s enduring link between faith, memory, and national resilience. Today, the Red Church remains both a sacred space and a civic emblem—one that continues to unite the people of Minsk through history, faith, and remembrance.

Beyond its architectural charm, the Red Church carries a layered and often tragic history. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, it was seized by Soviet authorities and transformed into a theater and later a film studio—its religious role completely suppressed. It was not until the late 20th century, during Belarus’s national awakening, that the church was restored to the Roman Catholic community, becoming once again a place of worship and a focal point of local identity.

Inside, visitors will find a serene interior defined by stained-glass windows, symbolic murals, and a calm atmosphere that contrasts the bustle of Independence Square outside. The surrounding grounds host memorials to those who perished during wars and political repressions, reinforcing the church’s enduring link between faith, memory, and national resilience. Today, the Red Church remains both a sacred space and a civic emblem—one that continues to unite the people of Minsk through history, faith, and remembrance.

2) Cathedral of St. Apostles Peter and Paul (must see)

The Cathedral of Saints Apostles Peter and Paul, fondly known as the “Yellow Church” for its distinctive façade, is the oldest surviving church in Minsk and a cornerstone of the city’s spiritual life. Construction began in 1612 with the help of monks from the Vilna Holy Spirit Monastery and was largely completed by 1613. Originally built alongside a monastery of the same name, the church served as a vital centre of Orthodox faith during a time when Belarus stood at the crossroads of Eastern and Western religious traditions. Its soft yellow Baroque-style exterior, with graceful proportions and twin towers, continues to make it one of Minsk’s most recognizable and cherished landmarks.

Architecturally, the cathedral combines Baroque and traditional Belarusian elements, giving it both grandeur and warmth. The interior preserves much of its early character, featuring a richly adorned iconostasis, gilded accents, and painted icons that radiate a sense of quiet devotion. The vaulted ceilings and balanced design reflect the craftsmanship of the early 17th century, while the atmosphere within invites reflection and reverence—a living link to centuries of Orthodox worship.

The cathedral’s history reflects Minsk’s enduring spirit. Damaged during the Great Northern War and Napoleon’s invasion, it was repeatedly restored, notably under Empress Catherine II in the 1790s and again in the 1870s. Closed by the Soviets in 1933 and used as a warehouse and archive, it briefly reopened during World War II before falling silent once more. In 1991, after decades of suppression, the church was revived as an active parish of the Belarusian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Today, the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul stands not only as a house of worship but also as a monument to Minsk’s endurance, unity, and cultural heritage.

Architecturally, the cathedral combines Baroque and traditional Belarusian elements, giving it both grandeur and warmth. The interior preserves much of its early character, featuring a richly adorned iconostasis, gilded accents, and painted icons that radiate a sense of quiet devotion. The vaulted ceilings and balanced design reflect the craftsmanship of the early 17th century, while the atmosphere within invites reflection and reverence—a living link to centuries of Orthodox worship.

The cathedral’s history reflects Minsk’s enduring spirit. Damaged during the Great Northern War and Napoleon’s invasion, it was repeatedly restored, notably under Empress Catherine II in the 1790s and again in the 1870s. Closed by the Soviets in 1933 and used as a warehouse and archive, it briefly reopened during World War II before falling silent once more. In 1991, after decades of suppression, the church was revived as an active parish of the Belarusian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Today, the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul stands not only as a house of worship but also as a monument to Minsk’s endurance, unity, and cultural heritage.

3) Cathedral of Saint Virgin Mary (must see)

The Cathedral of Saint Virgin Mary stands as one of Minsk’s most beautiful Baroque landmarks and a central symbol of Belarusian Catholic heritage. Located in the historic Upper Town, the cathedral was built between 1700 and 1710 by Jesuit monks as part of a larger monastic complex. Originally serving as a Jesuit church, it was dedicated to the Virgin Mary, reflecting the growing influence of the Jesuit Order in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the time. The twin-towered façade and ornate detailing embody the grandeur and optimism of early 18th-century Baroque architecture, which brought a touch of European sophistication to Minsk’s skyline.

Throughout its history, the cathedral has mirrored the city’s turbulent fate. After the suppression of the Jesuit Order in 1773, it became a parish church, later repurposed as an Orthodox cathedral under Russian rule, and even turned into a sports hall during the Soviet period. It wasn’t until 1993, following Belarus’s independence, that the building was fully restored and reconsecrated as a Catholic cathedral. Today, it serves as the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Minsk-Mohilev, once again fulfilling its original spiritual role.

Inside, visitors can admire the cathedral’s elegant stucco decorations, vaulted ceilings, and restored frescoes. The high altar, depicting the Virgin Mary surrounded by cherubs, draws the eye upward toward the luminous dome. Regular Mass services are held here, accompanied by organ music that resonates beautifully within the church’s acoustics. For those exploring Minsk’s Old Town, the Cathedral of Saint Virgin Mary offers not only architectural splendor but also a sense of resilience and renewal rooted in centuries of faith and history.

Throughout its history, the cathedral has mirrored the city’s turbulent fate. After the suppression of the Jesuit Order in 1773, it became a parish church, later repurposed as an Orthodox cathedral under Russian rule, and even turned into a sports hall during the Soviet period. It wasn’t until 1993, following Belarus’s independence, that the building was fully restored and reconsecrated as a Catholic cathedral. Today, it serves as the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Minsk-Mohilev, once again fulfilling its original spiritual role.

Inside, visitors can admire the cathedral’s elegant stucco decorations, vaulted ceilings, and restored frescoes. The high altar, depicting the Virgin Mary surrounded by cherubs, draws the eye upward toward the luminous dome. Regular Mass services are held here, accompanied by organ music that resonates beautifully within the church’s acoustics. For those exploring Minsk’s Old Town, the Cathedral of Saint Virgin Mary offers not only architectural splendor but also a sense of resilience and renewal rooted in centuries of faith and history.

4) Saint Joseph Church (must see)

Minsk’s Saint Joseph Church, located in the historic Upper City, is a striking example of Baroque architecture in Belarus. Built in 1752 and originally serving as part of a Bernardine (Franciscan) monastery complex, the church was named after Saint Joseph and designed to evoke spiritual devotion and monastic serenity. Its three-aisled basilica form, with a taller central nave flanked by chapels, and its richly articulated western façade (with pilasters, capitals, volutes, and a triple-window porch) speak to the stylistic ambition of its builders.

The church and its adjacent monastery had a long and sometimes troubled history. The original wooden church of the Bernardines was destroyed by fire in 1644, and subsequent reconstructions followed a stone design. Yet through the centuries, fires in 1656, 1740, and 1835 necessitated repeated restoration efforts, culminating in the Baroque redesign of 1752. In the 19th century, the monastery was suppressed after the January Uprising and the complex was confiscated; by the 1860s, the church had been closed to worship and re-purposed as an archive facility.

Today, visitors will find the former church no longer serving liturgical functions but housing Belarus’s art, literature, scientific, and technical archives—holding over 200,000 items, including postwar city plans of Minsk. In 2022, efforts were made to restore the façade’s original Baroque color scheme under architect R. Zabieła, offering a renewed glimpse into its past Baroque splendor. For tourists wandering through Minsk’s Upper City, Saint Joseph Church is a compelling stop: a monument not only to religious architecture but also to Belarus’s layered cultural history, bridging faith, political change, and collective memory.

The church and its adjacent monastery had a long and sometimes troubled history. The original wooden church of the Bernardines was destroyed by fire in 1644, and subsequent reconstructions followed a stone design. Yet through the centuries, fires in 1656, 1740, and 1835 necessitated repeated restoration efforts, culminating in the Baroque redesign of 1752. In the 19th century, the monastery was suppressed after the January Uprising and the complex was confiscated; by the 1860s, the church had been closed to worship and re-purposed as an archive facility.

Today, visitors will find the former church no longer serving liturgical functions but housing Belarus’s art, literature, scientific, and technical archives—holding over 200,000 items, including postwar city plans of Minsk. In 2022, efforts were made to restore the façade’s original Baroque color scheme under architect R. Zabieła, offering a renewed glimpse into its past Baroque splendor. For tourists wandering through Minsk’s Upper City, Saint Joseph Church is a compelling stop: a monument not only to religious architecture but also to Belarus’s layered cultural history, bridging faith, political change, and collective memory.

5) Cathedral of Holy Spirit (must see)

If you’re visiting Minsk’s Upper Town, one of the most evocative and enduring landmarks you’ll encounter is the Holy Spirit Cathedral. Rising atop one of the city’s highest hills, this white-faced baroque monument has borne witness to centuries of spiritual, political, and cultural change.

The site itself is steeped in layers of history. Before the 17th century, it housed an Orthodox monastery dedicated to Saints Cosmas and Damian. In the early 1600s, under the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, control passed to the Bernardine Catholic order, who built the present stone church between 1633 and 1642 as part of a monastic complex. Over time, the structure endured wars, fires, and shifting religious allegiance. After 1860, it was transformed into an Orthodox church, and it eventually became the mother church of the Belarusian Orthodox Church.

Architecturally, the cathedral is a three-nave basilica crowned with twin towers flanking its façade, built in what is often called the Vilnius (or Belarusian) Baroque style. Inside, the richly decorated iconostasis (with icons from the Moscow academic school) forms a luminous backdrop to worship. Among its most treasured relics is the miraculous icon of the Mother of God “Minskaya,” believed by many faithful to grant special graces. You will also find the relics of Saint Sophia of Slutsk, a 17th-century noblewoman regarded as a defender of Orthodoxy in Belarus.

Today, the Holy Spirit Cathedral remains one of Minsk’s most beloved spiritual and cultural symbols. As you approach it through winding Upper Town streets, take your time to admire not just its graceful towers and elegant façade, but to imagine the many centuries of devotion and upheaval it has witnessed. Inside, the hushed atmosphere invites reflection on the layers of faith and identity that have shaped Belarus.

The site itself is steeped in layers of history. Before the 17th century, it housed an Orthodox monastery dedicated to Saints Cosmas and Damian. In the early 1600s, under the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, control passed to the Bernardine Catholic order, who built the present stone church between 1633 and 1642 as part of a monastic complex. Over time, the structure endured wars, fires, and shifting religious allegiance. After 1860, it was transformed into an Orthodox church, and it eventually became the mother church of the Belarusian Orthodox Church.

Architecturally, the cathedral is a three-nave basilica crowned with twin towers flanking its façade, built in what is often called the Vilnius (or Belarusian) Baroque style. Inside, the richly decorated iconostasis (with icons from the Moscow academic school) forms a luminous backdrop to worship. Among its most treasured relics is the miraculous icon of the Mother of God “Minskaya,” believed by many faithful to grant special graces. You will also find the relics of Saint Sophia of Slutsk, a 17th-century noblewoman regarded as a defender of Orthodoxy in Belarus.

Today, the Holy Spirit Cathedral remains one of Minsk’s most beloved spiritual and cultural symbols. As you approach it through winding Upper Town streets, take your time to admire not just its graceful towers and elegant façade, but to imagine the many centuries of devotion and upheaval it has witnessed. Inside, the hushed atmosphere invites reflection on the layers of faith and identity that have shaped Belarus.

6) Church of St. Mary Magdalena (must see)

The Church of Saint Mary Magdalene stands as a serene testament to faith and endurance in the heart of the Belarusian capital. Built in 1847 of brick, the Orthodox church replaced an earlier wooden chapel and became one of the city’s defining mid-19th-century landmarks. From its earliest days, the church served not only as a house of worship but also as a community centre, surrounded by a parish complex that included a school and a shelter.

Architecturally, the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene exemplifies the Russo-Byzantine style, softened by classical features characteristic of a transitional era in Orthodox design. Its dome rests on a solid drum, rising gracefully above arched openings and ornamented façades that convey both solemnity and harmony. The church forms part of a larger ensemble with the Storozhevskaya Gate and the Church of John the Forerunner, creating a cohesive historical nucleus that reflects Minsk’s layered spiritual and architectural heritage.

The 20th century brought deep challenges: after the revolution, the church was stripped of its property and closed in 1949. For decades, it housed the State Archive of Film and Photo Documents, its sacred silence replaced by reels of history. Yet in 1990, after years of state restrictions on worship, Saint Mary Magdalene’s became the first Minsk church to regain its license for religious services—an important milestone in the city’s spiritual revival.

Today, visitors find a thriving parish filled with devotion and history. Among its cherished treasures are a relic of Saint Mary Magdalene, brought in a solemn procession the same year the church reopened, a myrrh-streaming icon of Saint Nicholas that revealed a miracle in 2002, and a cross containing relics of saints gifted by Patriarch Alexy II. Together, they make the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene not only a monument of architecture but also a living witness to Minsk’s resilient faith.

Architecturally, the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene exemplifies the Russo-Byzantine style, softened by classical features characteristic of a transitional era in Orthodox design. Its dome rests on a solid drum, rising gracefully above arched openings and ornamented façades that convey both solemnity and harmony. The church forms part of a larger ensemble with the Storozhevskaya Gate and the Church of John the Forerunner, creating a cohesive historical nucleus that reflects Minsk’s layered spiritual and architectural heritage.

The 20th century brought deep challenges: after the revolution, the church was stripped of its property and closed in 1949. For decades, it housed the State Archive of Film and Photo Documents, its sacred silence replaced by reels of history. Yet in 1990, after years of state restrictions on worship, Saint Mary Magdalene’s became the first Minsk church to regain its license for religious services—an important milestone in the city’s spiritual revival.

Today, visitors find a thriving parish filled with devotion and history. Among its cherished treasures are a relic of Saint Mary Magdalene, brought in a solemn procession the same year the church reopened, a myrrh-streaming icon of Saint Nicholas that revealed a miracle in 2002, and a cross containing relics of saints gifted by Patriarch Alexy II. Together, they make the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene not only a monument of architecture but also a living witness to Minsk’s resilient faith.

7) Church of Holy Trinity (must see)

The Church of the Holy Trinity, also known as Saint Roch’s Church or the Church on the Golden Hill, stands among Minsk’s most cherished Catholic landmarks. Located in the Zolotaya Gorka district, it combines religious devotion, historical depth, and cultural vitality. Its origin is linked to a local legend about a doctor who, after helping the city overcome a cholera epidemic, threw gold coins onto his coat and called on townspeople to fund a new church on the site of a Catholic cemetery. There, a wooden statue of Saint Roch—protector against plagues and patron of surgeons—was placed and became the object of widespread veneration.

The current brick church was built between 1861 and 1864 in a refined Gothic style, with tall windows, a zinc roof, and a three-bell tower whose chimes once echoed across the city. It was consecrated in 1864 under the names of Saint Roch and the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Thousands of pilgrims came to pray before the statue of Saint Roch each year on August 16, considering it miraculous. By 1908, the church was a well-established landmark, symbolizing both faith and community resilience in Minsk’s rapidly changing landscape.

Following the Russian Revolution, the church was closed and stripped of its valuables. The revered statue of Saint Roch disappeared, and during World War II, the building suffered heavy bombing damage. In 1983, restoration began, and a Czech-made pipe organ was installed as part of plans to convert the structure into a chamber music hall for the Belarusian State Philharmonic.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the church was returned to the faithful. Religious services resumed in 1991, and a new statue of Saint Roch was sculpted by Valerian Yanushkevich in 1998. Today, the Church of the Holy Trinity serves both as a sacred space and a cultural venue, hosting organ concerts and English-language masses every Sunday.

The current brick church was built between 1861 and 1864 in a refined Gothic style, with tall windows, a zinc roof, and a three-bell tower whose chimes once echoed across the city. It was consecrated in 1864 under the names of Saint Roch and the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Thousands of pilgrims came to pray before the statue of Saint Roch each year on August 16, considering it miraculous. By 1908, the church was a well-established landmark, symbolizing both faith and community resilience in Minsk’s rapidly changing landscape.

Following the Russian Revolution, the church was closed and stripped of its valuables. The revered statue of Saint Roch disappeared, and during World War II, the building suffered heavy bombing damage. In 1983, restoration began, and a Czech-made pipe organ was installed as part of plans to convert the structure into a chamber music hall for the Belarusian State Philharmonic.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the church was returned to the faithful. Religious services resumed in 1991, and a new statue of Saint Roch was sculpted by Valerian Yanushkevich in 1998. Today, the Church of the Holy Trinity serves both as a sacred space and a cultural venue, hosting organ concerts and English-language masses every Sunday.

8) Church of Alexander Nevsky

The Church of Alexander Nevsky in Minsk stands as one of the city’s most revered Orthodox landmarks, deeply rooted in both faith and military history. Built in 1898, the church was dedicated to Saint Alexander Nevsky, the medieval Russian prince and military leader renowned for his defense of the Orthodox faith. Its construction was initiated to serve the soldiers of the Minsk garrison, reflecting the close connection between the church and the military community at the turn of the 20th century. Designed by architect Vladimir Struyev, the building is a notable example of Russian Revival architecture, combining traditional Byzantine forms with elements typical of late imperial ecclesiastical design.

The church’s brick façade, crowned with graceful onion domes, exudes solemn beauty. Inside, visitors encounter a serene space marked by soft light, rich iconography, and the scent of candle wax—a timeless atmosphere that has endured through wars and political upheavals. During the Soviet period, the church was closed, its treasures looted, and its role as a spiritual centre suppressed. Yet, unlike many others, it escaped demolition and was one of the first churches in Minsk to reopen for worship after World War II, symbolizing the survival of faith through adversity.

Today, the Church of Alexander Nevsky continues to serve as an active parish and a site of remembrance for soldiers who died in service. Visitors come not only for its religious significance but also for its tranquil setting and historical resonance, making it a moving testament to Belarus’s enduring spiritual and cultural heritage.

The church’s brick façade, crowned with graceful onion domes, exudes solemn beauty. Inside, visitors encounter a serene space marked by soft light, rich iconography, and the scent of candle wax—a timeless atmosphere that has endured through wars and political upheavals. During the Soviet period, the church was closed, its treasures looted, and its role as a spiritual centre suppressed. Yet, unlike many others, it escaped demolition and was one of the first churches in Minsk to reopen for worship after World War II, symbolizing the survival of faith through adversity.

Today, the Church of Alexander Nevsky continues to serve as an active parish and a site of remembrance for soldiers who died in service. Visitors come not only for its religious significance but also for its tranquil setting and historical resonance, making it a moving testament to Belarus’s enduring spiritual and cultural heritage.

Walking Tours in Minsk, Belarus

Create Your Own Walk in Minsk

Creating your own self-guided walk in Minsk is easy and fun. Choose the city attractions that you want to see and a walk route map will be created just for you. You can even set your hotel as the start point of the walk.

Minsk Introduction Walking Tour

When in Minsk, visitors are sure to discover a fantastic range of exotic places, valuable architectural spots, and cultural venues which combine to create Minsk's unforgettable landmarks. Do not hesitate to experience the deep culture of Minsk.

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.6 Km or 2.2 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.6 Km or 2.2 Miles

The Most Popular Cities

/ view all