Audio Guide: May Avenue Walking Tour (Self Guided), Buenos Aires

May Avenue is one of Buenos Aires’ most emblematic boulevards, a grand east–west axis that reflects the city’s political, cultural, and architectural evolution. Its name honors the May Revolution of 1810, when residents of Buenos Aires removed the Spanish viceroy and initiated the process that ultimately led to Argentina’s independence.

Plans for a monumental boulevard connecting the seat of the executive power, the Pink House, with the seat of the legislative branch, the National Congress, first emerged in the late 19th century, during an era of major urban reforms inspired by European capitals. The municipal public works director, Juan Antonio Buschiazzo, together with municipal engineers, envisioned an avenue that would give Buenos Aires the elegance of Parisian boulevards.

Construction began in the 1880s, and the avenue was inaugurated in 1894. From the beginning, the boulevard was celebrated for its unified aesthetic: continuous facades, similar cornice heights, and a harmonious blend of architectural styles. Over time, the avenue became a showcase of Beaux-Arts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and Spanish Academicist architecture. Notable buildings such as the Buenos Aires House of Culture, the Hotel Castelar, and the Barolo Palace made it one of the most distinctive streets in the city.

May Avenue quickly developed into a cultural and political corridor. Its cafes — especially Cafe Tortoni, founded in 1858 and moved here in 1898 — became gathering places for artists, writers, and intellectuals. Theaters and hotels flourished along the route, turning the boulevard into a fashionable promenade. It also became the stage for major political parades, demonstrations, and presidential processions, cementing its status as a symbolic artery of Argentine public life.

In the early 20th century, May Avenue was also shaped by immigration, particularly from Spain. Many Spanish institutions, publishing houses, and cultural centers established themselves here, giving the avenue its reputation as the heart of the Spanish community — a reputation strengthened by the opening of the Avenida Theater in 1908.

Today, the avenue remains a protected heritage area and an essential part of Buenos Aires’ identity. Its name continues to evoke the revolutionary spirit of May 1810, while its architecture and atmosphere preserve the city’s cosmopolitan past and its long tradition of civic expression.

Plans for a monumental boulevard connecting the seat of the executive power, the Pink House, with the seat of the legislative branch, the National Congress, first emerged in the late 19th century, during an era of major urban reforms inspired by European capitals. The municipal public works director, Juan Antonio Buschiazzo, together with municipal engineers, envisioned an avenue that would give Buenos Aires the elegance of Parisian boulevards.

Construction began in the 1880s, and the avenue was inaugurated in 1894. From the beginning, the boulevard was celebrated for its unified aesthetic: continuous facades, similar cornice heights, and a harmonious blend of architectural styles. Over time, the avenue became a showcase of Beaux-Arts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and Spanish Academicist architecture. Notable buildings such as the Buenos Aires House of Culture, the Hotel Castelar, and the Barolo Palace made it one of the most distinctive streets in the city.

May Avenue quickly developed into a cultural and political corridor. Its cafes — especially Cafe Tortoni, founded in 1858 and moved here in 1898 — became gathering places for artists, writers, and intellectuals. Theaters and hotels flourished along the route, turning the boulevard into a fashionable promenade. It also became the stage for major political parades, demonstrations, and presidential processions, cementing its status as a symbolic artery of Argentine public life.

In the early 20th century, May Avenue was also shaped by immigration, particularly from Spain. Many Spanish institutions, publishing houses, and cultural centers established themselves here, giving the avenue its reputation as the heart of the Spanish community — a reputation strengthened by the opening of the Avenida Theater in 1908.

Today, the avenue remains a protected heritage area and an essential part of Buenos Aires’ identity. Its name continues to evoke the revolutionary spirit of May 1810, while its architecture and atmosphere preserve the city’s cosmopolitan past and its long tradition of civic expression.

How it works: Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" from Apple App Store or Google Play Store to your mobile phone or tablet. The app turns your mobile device into a personal tour guide and its built-in GPS navigation functions guide you from one tour stop to next. The app works offline, so no data plan is needed when traveling abroad.

May Avenue Walking Tour Map

Guide Name: May Avenue Walking Tour

Guide Location: Argentina » Buenos Aires (See other walking tours in Buenos Aires)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 13

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.3 Km or 1.4 Miles

Author: irenes

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

Guide Location: Argentina » Buenos Aires (See other walking tours in Buenos Aires)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 13

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.3 Km or 1.4 Miles

Author: irenes

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

- Casa Rosada Museum (Pink House Museum)

- Monument of General Manuel Belgrano

- May Pyramid

- Metropolitan Cathedral

- Museum of the Cabildo and the May Revolution

- Buenos Aires House of Culture

- Café Tortoni

- Don Quijote Monument

- Avenida Theater

- Palacio Barolo (Barolo Palace)

- Monument to Mariano Moreno

- Monument of the Two Congresses

- National Congress

1) Casa Rosada Museum (Pink House Museum) (must see)

Pink House Museum is located inside the main office complex of the President of Argentina, known as Pink House. The museum features exhibits that explore more than 100 years of the Pink House’s role as the seat of power in Argentina.

The museum displays an extensive collection of objects belonging to Argentine leaders throughout the country’s history. The museum was created to exhibit presidential memorabilia. Among its holdings are artifacts from the remains of an old fort that once occupied the site, as well as elements from the former Customs House, designed by British architect Edward Taylor. At one time, the Customs House was the largest building in Argentina.

Exhibits include books, furniture, swords, uniforms, and carriages used by former presidents. More personal items—such as flatware and dolls used by presidential families—are also on display. Several underground rooms correspond to the foundations of earlier government structures that once stood here. In 2011, a modern extension was added to house a mural by Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros—one of his most powerful and immersive works. There is also a dedicated section honoring Eva Perón, former First Lady of Argentina. A lesser-known highlight is the preserved section of colonial-era tunnels, offering a glimpse into the early defensive layout of Buenos Aires.

Tip:

Visitors must reserve in advance to join the free museum tours which are conducted in Spanish. These tours are absolutely worth it and easy to book online. On weekends, you can also visit the Pink House itself on a free guided tour available in both Spanish and English, also with a reservation.

The museum displays an extensive collection of objects belonging to Argentine leaders throughout the country’s history. The museum was created to exhibit presidential memorabilia. Among its holdings are artifacts from the remains of an old fort that once occupied the site, as well as elements from the former Customs House, designed by British architect Edward Taylor. At one time, the Customs House was the largest building in Argentina.

Exhibits include books, furniture, swords, uniforms, and carriages used by former presidents. More personal items—such as flatware and dolls used by presidential families—are also on display. Several underground rooms correspond to the foundations of earlier government structures that once stood here. In 2011, a modern extension was added to house a mural by Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros—one of his most powerful and immersive works. There is also a dedicated section honoring Eva Perón, former First Lady of Argentina. A lesser-known highlight is the preserved section of colonial-era tunnels, offering a glimpse into the early defensive layout of Buenos Aires.

Tip:

Visitors must reserve in advance to join the free museum tours which are conducted in Spanish. These tours are absolutely worth it and easy to book online. On weekends, you can also visit the Pink House itself on a free guided tour available in both Spanish and English, also with a reservation.

2) Monument of General Manuel Belgrano

The Monument of General Manuel Belgrano, standing proudly in front of the Pink House, was designed by sculptors Louis-Robert Carrier-Belleuse and Manuel de Santa Coloma, commemorating one of Argentina’s most influential historical figures. Manuel Belgrano was a key figure in the Argentine Wars of Independence and is considered one of the country's primary liberators. Aside from his military achievements, Belgrano is also credited with designing the Argentine flag.

The monument, crafted from bronze, features Belgrano on horseback holding the flag of Argentina. It sits atop a granite pedestal, symbolizing the strength and resilience of the nation he helped to forge. The project was commissioned in 1870 by General Bartolomé Mitre, politicians Enrique Martínez, and Manuel José Guerrico. After years of work, the monument was completed in 1872 and was officially inaugurated on September 24, 1873.

Today, it stands as a proud testament to Belgrano's legacy, not just as a military leader, but as a symbol of Argentina's fight for freedom and independence. In addition to its historical significance, the monument's location at May Square makes it a central point of reflection in Buenos Aires, particularly during national celebrations and political events.

The monument, crafted from bronze, features Belgrano on horseback holding the flag of Argentina. It sits atop a granite pedestal, symbolizing the strength and resilience of the nation he helped to forge. The project was commissioned in 1870 by General Bartolomé Mitre, politicians Enrique Martínez, and Manuel José Guerrico. After years of work, the monument was completed in 1872 and was officially inaugurated on September 24, 1873.

Today, it stands as a proud testament to Belgrano's legacy, not just as a military leader, but as a symbol of Argentina's fight for freedom and independence. In addition to its historical significance, the monument's location at May Square makes it a central point of reflection in Buenos Aires, particularly during national celebrations and political events.

3) May Pyramid

The May Pyramid, commemorating the May Revolution in Argentina, is the oldest national monument in Buenos Aires and in 1942, it was declared a National Historic Monument. Designed by architect Pedro Vicente Cañete and sculpture professor Juan Gaspar Hernández, the pyramid was completed in 1811. It was inaugurated on May 25, 1811, although it was not fully finished at that time. The original pyramid stood 13 meters tall on a 2-meter pedestal.

The current structure was built over the original pyramid designed by Cañete. In the mid-19th century, architect Prilidiano Pueyrredón was tasked with redesigning the monument. Pueyrredón transformed the old pyramid into a more ornate and artistic structure. The top of the May Pyramid was adorned with a statue of Liberty, sculpted by French artist Joseph Dubourdieu. The base of the pyramid originally featured terracotta statues by Dubourdieu symbolizing Industry, Commerce, Science, and the Arts, which were later removed and replaced with other carvings— national shield, laurel wreaths.

In 1912, the pyramid was relocated 63 meters east of its original location to make way for a larger monument that was ultimately never built. The ashes of Azucena Villaflor, the founder of the Mothers of the May Square protest movement, are buried at the base of the pyramid. Villaflor's organization, composed of mothers whose children were disappeared during Argentina's last military dictatorship, played a crucial role in the fight for human rights and accountability.

The current structure was built over the original pyramid designed by Cañete. In the mid-19th century, architect Prilidiano Pueyrredón was tasked with redesigning the monument. Pueyrredón transformed the old pyramid into a more ornate and artistic structure. The top of the May Pyramid was adorned with a statue of Liberty, sculpted by French artist Joseph Dubourdieu. The base of the pyramid originally featured terracotta statues by Dubourdieu symbolizing Industry, Commerce, Science, and the Arts, which were later removed and replaced with other carvings— national shield, laurel wreaths.

In 1912, the pyramid was relocated 63 meters east of its original location to make way for a larger monument that was ultimately never built. The ashes of Azucena Villaflor, the founder of the Mothers of the May Square protest movement, are buried at the base of the pyramid. Villaflor's organization, composed of mothers whose children were disappeared during Argentina's last military dictatorship, played a crucial role in the fight for human rights and accountability.

4) Metropolitan Cathedral (must see)

The Buenos Aires Metropolitan Cathedral is the most significant Catholic church in the city. The site was originally designated for a church in 1580, and several structures were built throughout the 1600s. However, the current building dates to the early 1700s, with a Greek Revival facade added in the early 1800s. In 1836, the church was formally designated as the cathedral.

As you admire the cathedral's facade, you'll observe 12 Neo-Classical columns, symbolizing the twelve apostles. Its frontispiece features a large bas-relief depicting two important figures from the Old Testament: Jacob and Joseph in Egypt, intended as a metaphor for national reconciliation after periods of civil conflict. Walking inside, the cathedral impresses with a 134-foot vaulted ceiling and five naves. Pay attention to the Venetian mosaic flooring, covering the entire interior floor of the cathedral. It illustrates a series of religious motifs and geometric designs crafted by Italian artisans in the late 19th century.

The cathedral’s oldest artwork is the 1671 Christ of Buenos Aires. To find it, walk down the central nave and turn right, where the Chapel of the Holy Christ appears among the first on that side; the wooden 17th-century image stands in a small altar niche and is easy to spot thanks to its expressive colonial style. The main gilded wood altarpiece, dating to 1785, rises at the far end of the central nave, directly facing visitors as they enter the cathedral. The monumental 1871 organ, with more than 3,500 pipes, is positioned above the entrance on the choir balcony and becomes visible when you look back toward the main doors. The beautifully preserved 18th-century wooden pulpit, decorated with gold leaf, stands to the left of the central nave, raised on a carved base and easily noticed as you walk toward the altar.

Several important memorials are housed inside the cathedral, each easy to locate as you move through the nave. To the left of the main altar, an ornate marble mausoleum holds the remains of General José de San Martín, one of Latin America’s great liberators; the monument is guarded by statues representing Argentina, Peru, and Chile. Just beside it stands the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of Argentine Independence, marked by a simple yet solemn inscription.

Pope Francis celebrated Mass here during his years as Archbishop Jorge Bergoglio before his election as Pope in 2013. Today, the cathedral houses the Pope Francis Museum, displaying some of his personal items, liturgical garments, and photographs documenting his time in Buenos Aires.

As you admire the cathedral's facade, you'll observe 12 Neo-Classical columns, symbolizing the twelve apostles. Its frontispiece features a large bas-relief depicting two important figures from the Old Testament: Jacob and Joseph in Egypt, intended as a metaphor for national reconciliation after periods of civil conflict. Walking inside, the cathedral impresses with a 134-foot vaulted ceiling and five naves. Pay attention to the Venetian mosaic flooring, covering the entire interior floor of the cathedral. It illustrates a series of religious motifs and geometric designs crafted by Italian artisans in the late 19th century.

The cathedral’s oldest artwork is the 1671 Christ of Buenos Aires. To find it, walk down the central nave and turn right, where the Chapel of the Holy Christ appears among the first on that side; the wooden 17th-century image stands in a small altar niche and is easy to spot thanks to its expressive colonial style. The main gilded wood altarpiece, dating to 1785, rises at the far end of the central nave, directly facing visitors as they enter the cathedral. The monumental 1871 organ, with more than 3,500 pipes, is positioned above the entrance on the choir balcony and becomes visible when you look back toward the main doors. The beautifully preserved 18th-century wooden pulpit, decorated with gold leaf, stands to the left of the central nave, raised on a carved base and easily noticed as you walk toward the altar.

Several important memorials are housed inside the cathedral, each easy to locate as you move through the nave. To the left of the main altar, an ornate marble mausoleum holds the remains of General José de San Martín, one of Latin America’s great liberators; the monument is guarded by statues representing Argentina, Peru, and Chile. Just beside it stands the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of Argentine Independence, marked by a simple yet solemn inscription.

Pope Francis celebrated Mass here during his years as Archbishop Jorge Bergoglio before his election as Pope in 2013. Today, the cathedral houses the Pope Francis Museum, displaying some of his personal items, liturgical garments, and photographs documenting his time in Buenos Aires.

5) Museum of the Cabildo and the May Revolution

As many of the Argentina's attractions, The National Museum of the Cabildo and the May Revolution tells the story of Spanish colonial and the 1810 May Revolution that ended Spanish supremacy in the region. It preserves government and revolutionary exhibits from the 18th and early 19th centuries, offering a clear picture of the political and social tensions that shaped the birth of the nation.

The Cabildo that houses the museum was originally the seat of the colonial government. After the May Revolution of 1810, which unfolded directly in the plaza in front of the building, it became the city hall. Today it is one of the few surviving colonial structures in Buenos Aires. Much of the original facade and several arcades were demolished in the late 19th century to make way for two major avenues, and the current appearance is the result of a 1940 reconstruction based on plans by architect Mario Buschiazzo, who restored the building to its historic colonial style.

The museum’s exhibits include paintings, artifacts, weapons, maps, documents, costumes, jewelry, and photographs, all illustrating life in the city during the colonial period and the revolution. An ornamental well from 1835 is the only surviving architectural element of the original Cabildo, which you can find directly in the center of the courtyard. A crafts fair, featuring handmade goods from local artisans, takes place on Thursdays and Fridays in the courtyard.

Inside, visitors can explore several rooms detailing the city’s early history, including displays of administrative life, religious influence, and the events that led to the formation of the First National Government.

Tip:

The museum provides English-language cards with translations of all signs and exhibit information. Don’t forget to go upstairs where the balcony offers excellent views of the square and its surrounding historic buildings.

The Cabildo that houses the museum was originally the seat of the colonial government. After the May Revolution of 1810, which unfolded directly in the plaza in front of the building, it became the city hall. Today it is one of the few surviving colonial structures in Buenos Aires. Much of the original facade and several arcades were demolished in the late 19th century to make way for two major avenues, and the current appearance is the result of a 1940 reconstruction based on plans by architect Mario Buschiazzo, who restored the building to its historic colonial style.

The museum’s exhibits include paintings, artifacts, weapons, maps, documents, costumes, jewelry, and photographs, all illustrating life in the city during the colonial period and the revolution. An ornamental well from 1835 is the only surviving architectural element of the original Cabildo, which you can find directly in the center of the courtyard. A crafts fair, featuring handmade goods from local artisans, takes place on Thursdays and Fridays in the courtyard.

Inside, visitors can explore several rooms detailing the city’s early history, including displays of administrative life, religious influence, and the events that led to the formation of the First National Government.

Tip:

The museum provides English-language cards with translations of all signs and exhibit information. Don’t forget to go upstairs where the balcony offers excellent views of the square and its surrounding historic buildings.

6) Buenos Aires House of Culture

Originally built as the headquarters of the influential newspaper La Prensa, the Buenos Aires House of Culture will always catch your eye as you walk through the Montserrat district of Argentina’s capital. In 1894, José Clemente Paz, owner of the newspaper, replaced its old headquarters with a grand new building on May Avenue. Architects Carlos Agote and Alberto Gainza, both trained in Paris, designed it in the Beaux-Arts style, drawing inspiration from the work of French architect Charles Garnier.

The building was inaugurated in 1898 during a ceremony attended by approximately 20,000 people. Its facade is especially notable for its tall spire, crowned with a gilded bronze statue symbolizing freedom of the press.

Inside the spire is a historic siren, installed in 1900 to announce major world events. It was sounded only five times in the past century: after the assassination of King Umberto I in 1900, during the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, to celebrate Argentina’s 1978 FIFA World Cup victory, during the Falklands War in 1982, and at Raúl Alfonsín’s 1983 presidential inauguration, marking the return of democracy.

The building’s interior was meticulously crafted using mostly imported materials. It features Sprague elevators from the United States, Boulanger mosaic tiles you may observe under your feet as you move through the ground floor, clocks designed by the master horologist Paul Garnier, and wrought-iron work from Val d’Osne in France. The highlight of the first floor is the Golden Salon, decorated with frescoes by Italian-born painters Reynaldo Giudici and Nazareno Orlandi.

Recognized today as the House of Culture, the building was declared a National Historic Monument in 1995. The former passageway connecting it to Buenos Aires City Hall has been converted into the Ana Díaz Salon, which now hosts rotating art exhibitions featuring local and national artists, photography, painting, and contemporary installations. Labels and panels usually provide background in Spanish, and sometimes in English.

The building was inaugurated in 1898 during a ceremony attended by approximately 20,000 people. Its facade is especially notable for its tall spire, crowned with a gilded bronze statue symbolizing freedom of the press.

Inside the spire is a historic siren, installed in 1900 to announce major world events. It was sounded only five times in the past century: after the assassination of King Umberto I in 1900, during the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, to celebrate Argentina’s 1978 FIFA World Cup victory, during the Falklands War in 1982, and at Raúl Alfonsín’s 1983 presidential inauguration, marking the return of democracy.

The building’s interior was meticulously crafted using mostly imported materials. It features Sprague elevators from the United States, Boulanger mosaic tiles you may observe under your feet as you move through the ground floor, clocks designed by the master horologist Paul Garnier, and wrought-iron work from Val d’Osne in France. The highlight of the first floor is the Golden Salon, decorated with frescoes by Italian-born painters Reynaldo Giudici and Nazareno Orlandi.

Recognized today as the House of Culture, the building was declared a National Historic Monument in 1995. The former passageway connecting it to Buenos Aires City Hall has been converted into the Ana Díaz Salon, which now hosts rotating art exhibitions featuring local and national artists, photography, painting, and contemporary installations. Labels and panels usually provide background in Spanish, and sometimes in English.

7) Café Tortoni

Cafe Tortoni, established in 1858 by a French immigrant, takes its name from the Parisian cafe on Boulevard des Italiens known as Tortoni, a favorite meeting place of the Parisian cultural elite during the 19th century. The design and atmosphere of the cafe reflect the elegant late-19th-century European cafe culture.

The cafe’s current location once housed the “Scottish Temple”, while Cafe Tortoni itself originally operated at the intersection of Rivadavia and Esmeralda streets. In 1880, it moved to its present site, although the entrance then faced Rivadavia Street. In 1898, a new entrance was opened on May Avenue, accompanied by a redesigned facade by architect Alejandro Christophersen.

Over the decades, Cafe Tortoni has welcomed countless notable figures, including politicians such as Lisandro de la Torre and Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear; beloved cultural icons like film actor and tango singer Carlos Gardel and racing driver Juan Manuel Fangio; and international visitors such as physicist Albert Einstein, poet Federico García Lorca, politician Hillary Clinton, actor Robert Duvall, and former King of Spain Juan Carlos I.

Today, the cafe’s basement functions as a venue for jazz and tango performances, as well as book presentations and poetry contests. Cafe Tortoni has meticulously preserved much of its original decor, including its historic library, and continues to offer traditional activities such as billiards, dominoes, and dice in its rear rooms.

The cafe’s current location once housed the “Scottish Temple”, while Cafe Tortoni itself originally operated at the intersection of Rivadavia and Esmeralda streets. In 1880, it moved to its present site, although the entrance then faced Rivadavia Street. In 1898, a new entrance was opened on May Avenue, accompanied by a redesigned facade by architect Alejandro Christophersen.

Over the decades, Cafe Tortoni has welcomed countless notable figures, including politicians such as Lisandro de la Torre and Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear; beloved cultural icons like film actor and tango singer Carlos Gardel and racing driver Juan Manuel Fangio; and international visitors such as physicist Albert Einstein, poet Federico García Lorca, politician Hillary Clinton, actor Robert Duvall, and former King of Spain Juan Carlos I.

Today, the cafe’s basement functions as a venue for jazz and tango performances, as well as book presentations and poetry contests. Cafe Tortoni has meticulously preserved much of its original decor, including its historic library, and continues to offer traditional activities such as billiards, dominoes, and dice in its rear rooms.

8) Don Quijote Monument

This bronze sculpture of the anti-hero Don Quixote marks one of the liveliest points in central Buenos Aires. Gifted by the Spanish Government in 1980 for the city’s 400th anniversary, it is unusual for the way Don Quixote and his horse seem to emerge from rough stone, their partially embedded forms creating a vivid black-and-white contrast best appreciated from the front.

The monument was created by Aurelio Teno, a Spanish sculptor internationally recognized for his many interpretations of Don Quixote. Far larger than most of his works, this version rises 15 meters high and weighs an extraordinary 200 tonnes. It was cast and assembled in Uruguay, where Teno worked with a team of seven engineers and more than one hundred laborers over a period of roughly six months before the sculpture was transported to Argentina.

Don Quixote himself is the tragicomic hero of Miguel de Cervantes’ masterpiece Don Quixote, considered one of the most influential novels ever written. The character, a nobleman driven mad by chivalric tales, sets out to “restore justice” to the world—often confusing reality with fantasy. As a symbol, he represents idealism, imagination, and the struggle between dreams and reality, themes culturally treasured in both Spain and Latin America. The monument was installed in Buenos Aires as a tribute not only to the city’s anniversary but also to its deep historical and cultural ties with Spain.

The monument was created by Aurelio Teno, a Spanish sculptor internationally recognized for his many interpretations of Don Quixote. Far larger than most of his works, this version rises 15 meters high and weighs an extraordinary 200 tonnes. It was cast and assembled in Uruguay, where Teno worked with a team of seven engineers and more than one hundred laborers over a period of roughly six months before the sculpture was transported to Argentina.

Don Quixote himself is the tragicomic hero of Miguel de Cervantes’ masterpiece Don Quixote, considered one of the most influential novels ever written. The character, a nobleman driven mad by chivalric tales, sets out to “restore justice” to the world—often confusing reality with fantasy. As a symbol, he represents idealism, imagination, and the struggle between dreams and reality, themes culturally treasured in both Spain and Latin America. The monument was installed in Buenos Aires as a tribute not only to the city’s anniversary but also to its deep historical and cultural ties with Spain.

9) Avenida Theater

The Avenida Theater was built in the early 20th century to provide Buenos Aires with a grand stage dedicated to Spanish-language drama, especially zarzuela—a popular Spanish theatrical form that blends spoken dialogue with operatic-style music. From the start, it became the city’s leading venue for this tradition.

The theater opened in 1908 with Justice Without Revenge by Spanish playwright Lope de Vega, directed by María Guerrero, one of the most influential figures in bringing classical Spanish theater to Argentina. Through the 1920s and 1930s, the Avenida Theater flourished as the main home of Spanish drama, hosting landmark works such as Blood Wedding in 1933 by playwright Federico García Lorca. It also staged operettas, zarzuelas, and major musical events, including a 1939 charity performance of Aida supporting Spanish organizations after the Civil War.

By mid-century, cultural tastes shifted, and the Avenida Theater increasingly turned to Broadway musicals and opera. A celebrated production of La Traviata in 1967 highlighted this new direction. Later, under producer Faustino García, the theater revived the zarzuela tradition with the return of conductor Federico Moreno Torroba in 1970.

Argentina’s last military dictatorship forced its closure in 1977, and a devastating fire in 1979 nearly destroyed it. After years standing in ruins, the Avenida Theater finally reopened on 19 June 1994, though the upper floors—once part of the historic Hotel Castilla—were never rebuilt.

The theater opened in 1908 with Justice Without Revenge by Spanish playwright Lope de Vega, directed by María Guerrero, one of the most influential figures in bringing classical Spanish theater to Argentina. Through the 1920s and 1930s, the Avenida Theater flourished as the main home of Spanish drama, hosting landmark works such as Blood Wedding in 1933 by playwright Federico García Lorca. It also staged operettas, zarzuelas, and major musical events, including a 1939 charity performance of Aida supporting Spanish organizations after the Civil War.

By mid-century, cultural tastes shifted, and the Avenida Theater increasingly turned to Broadway musicals and opera. A celebrated production of La Traviata in 1967 highlighted this new direction. Later, under producer Faustino García, the theater revived the zarzuela tradition with the return of conductor Federico Moreno Torroba in 1970.

Argentina’s last military dictatorship forced its closure in 1977, and a devastating fire in 1979 nearly destroyed it. After years standing in ruins, the Avenida Theater finally reopened on 19 June 1994, though the upper floors—once part of the historic Hotel Castilla—were never rebuilt.

10) Palacio Barolo (Barolo Palace) (must see)

The Barolo Palace, commissioned by Argentine textile magnate Luis Barolo, was designed to house offices and stood as the tallest building in Buenos Aires until 1936 . Barolo hired Italian architect Mario Palanti in 1910, sharing the common fear among some Europeans of the era that Europe might collapse under the pressures of war. Palanti, an admirer of Dante Alighieri, designed the building as a symbolic architectural interpretation of The Divine Comedy.

The structure has 24 floors—2 underground and 22 above—with the basements and ground floor representing Hell, the first through fifteenth floors symbolizing Purgatory, and the sixteenth through twenty-second floors representing Paradise. The building’s height of 100 meters exceeded the legal limit for May Avenue, but Mayor Luis Cantilo granted a special exception to allow its ambitious scale. Construction was completed in 1923, and the building was inaugurated with a blessing from the papal representative, Monsignor Giovanni Beda Cardinali.

A remarkable architectural detail is the building’s lighthouse, designed to mirror the one atop the now-demolished Salvo Palace in Montevideo—also a Palanti design—symbolizing the spiritual link between the two sides of the River Plate. The lighthouse once projected a powerful rotating beam out to sea; today, it operates during special events and night tours. The building’s interior is rich in symbolic numerology: 22 floors for the 22 stanzas of Dante’s cantos, and 9 vaults representing the nine circles, terraces, and spheres of the afterlife.

Bilingual English and Spanish tours guide visitors through the Dante-inspired design and the story of its visionary owner. The upper-floor balconies offer panoramic views of Buenos Aires, and the lighthouse balcony provides one of the most dramatic night viewpoints in the city. The Barolo Palace was declared a National Historic Monument in 1997.

Tip:

All tours require advance reservations—check the official website for exact dates and times. Night tours are well worth the extra cost, offering breathtaking views from the lighthouse and a relaxed wine tasting to end the experience.

The structure has 24 floors—2 underground and 22 above—with the basements and ground floor representing Hell, the first through fifteenth floors symbolizing Purgatory, and the sixteenth through twenty-second floors representing Paradise. The building’s height of 100 meters exceeded the legal limit for May Avenue, but Mayor Luis Cantilo granted a special exception to allow its ambitious scale. Construction was completed in 1923, and the building was inaugurated with a blessing from the papal representative, Monsignor Giovanni Beda Cardinali.

A remarkable architectural detail is the building’s lighthouse, designed to mirror the one atop the now-demolished Salvo Palace in Montevideo—also a Palanti design—symbolizing the spiritual link between the two sides of the River Plate. The lighthouse once projected a powerful rotating beam out to sea; today, it operates during special events and night tours. The building’s interior is rich in symbolic numerology: 22 floors for the 22 stanzas of Dante’s cantos, and 9 vaults representing the nine circles, terraces, and spheres of the afterlife.

Bilingual English and Spanish tours guide visitors through the Dante-inspired design and the story of its visionary owner. The upper-floor balconies offer panoramic views of Buenos Aires, and the lighthouse balcony provides one of the most dramatic night viewpoints in the city. The Barolo Palace was declared a National Historic Monument in 1997.

Tip:

All tours require advance reservations—check the official website for exact dates and times. Night tours are well worth the extra cost, offering breathtaking views from the lighthouse and a relaxed wine tasting to end the experience.

11) Monument to Mariano Moreno

The Monument to Mariano Moreno stands at the center of Mariano Moreno Square, honoring one of the key intellectual leaders of Argentina’s independence movement. Created in 1910 by the renowned Spanish sculptor Miguel Blay, the monument features a solemn seated figure of Moreno, carved in Carrara marble, symbolizing his role as the ideological force behind the May Revolution.

Mariano Moreno was a lawyer, journalist, and politician who played a decisive role in the May Revolution that ultimately led to Argentina’s declaration of independence from Spain. As secretary of the First Junta—the government that replaced the Spanish viceroy—he championed civil liberties, economic reform, and the spread of revolutionary ideas. He also founded The Gazette of Buenos Aires, the first Argentine newspaper, intended to inform and politically educate the public.

Visitors to Mariano Moreno Square will also see two other notable works. The Kilometer Zero Monument, created by Máximo and José Fioravanti; and “The Thinker”, the third original cast of Auguste Rodin’s commissioned in 1907 by Eduardo Schiaffino, director of the National Museum of Fine Arts.

Mariano Moreno was a lawyer, journalist, and politician who played a decisive role in the May Revolution that ultimately led to Argentina’s declaration of independence from Spain. As secretary of the First Junta—the government that replaced the Spanish viceroy—he championed civil liberties, economic reform, and the spread of revolutionary ideas. He also founded The Gazette of Buenos Aires, the first Argentine newspaper, intended to inform and politically educate the public.

Visitors to Mariano Moreno Square will also see two other notable works. The Kilometer Zero Monument, created by Máximo and José Fioravanti; and “The Thinker”, the third original cast of Auguste Rodin’s commissioned in 1907 by Eduardo Schiaffino, director of the National Museum of Fine Arts.

12) Monument of the Two Congresses

The Monument to the Two Congresses, the treasure of Congress Square, commemorates the centennial of the 1816 Argentine Declaration of Independence. Designed by Belgian architect Eugène D’Huicque and sculpted by Belgian artist Jules Lagae, the monument is one of the largest sculptural ensembles in Buenos Aires. At its center rises the Allegory of the Republic, a bronze female figure shown in forward motion, holding a laurel branch of victory. At her feet, intertwined snakes symbolize the forces that threaten the nation—an allegory of evil, discord, or corruption that the Republic must overcome.

Flanking the central figure are two additional allegorical groups, each represented by female figures. One symbolizes the 1813 Assembly, the landmark pre-independence body that abolished colonial practices such as torture and indigenous enslavement. The other represents the 1816 Congress of Tucumán, which issued Argentina’s formal Declaration of Independence. A separate figure of Abundance, often associated with agricultural prosperity, reinforces themes of national growth rather than directly representing the modern workforce.

The vast fountain at the base—the largest fountain in Buenos Aires—evokes the River Plate, with powerful bronze animals and cherubs symbolizing nature, vitality, and peace. In 1997, Congress Square, its neighboring squares, and the monument were collectively declared National Historic Monuments, recognizing their cultural, historical, and urban significance.

Flanking the central figure are two additional allegorical groups, each represented by female figures. One symbolizes the 1813 Assembly, the landmark pre-independence body that abolished colonial practices such as torture and indigenous enslavement. The other represents the 1816 Congress of Tucumán, which issued Argentina’s formal Declaration of Independence. A separate figure of Abundance, often associated with agricultural prosperity, reinforces themes of national growth rather than directly representing the modern workforce.

The vast fountain at the base—the largest fountain in Buenos Aires—evokes the River Plate, with powerful bronze animals and cherubs symbolizing nature, vitality, and peace. In 1997, Congress Square, its neighboring squares, and the monument were collectively declared National Historic Monuments, recognizing their cultural, historical, and urban significance.

13) National Congress

The Palace of the Argentine National Congress serves as the seat of Argentina’s bicameral legislature — making it a central monument of national democracy. Built between 1898 and 1906 from plans by Italian architect Vittorio Meano and completed by Argentine architect Julio Dormal, its grand neoclassical design features a majestic 80-meter bronze-plated dome.

If you plan to visit the Congress building, enter through the public entrance on Hipólito Yrigoyen Street and bring a passport or valid ID — identity is required before entry. Once inside, you’ll pass through a grand entrance hall framed by marble stairs and ornate decor; above the main doorway stands the bronze quadriga sculpture by Victor de Pol. The guided tour then takes you through some of the palace’s most impressive rooms, including the famous “Hall of the Lost Steps,” a ceremonial hall known for its expansive space, marble floors, chandeliers, and historic architecture.

You will also visit the legislative chambers of both houses — the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies — where laws are debated. Guided tours in Spanish and English are offered on most weekdays, though sessions may be canceled without notice if Parliament is in session.

If you plan to visit the Congress building, enter through the public entrance on Hipólito Yrigoyen Street and bring a passport or valid ID — identity is required before entry. Once inside, you’ll pass through a grand entrance hall framed by marble stairs and ornate decor; above the main doorway stands the bronze quadriga sculpture by Victor de Pol. The guided tour then takes you through some of the palace’s most impressive rooms, including the famous “Hall of the Lost Steps,” a ceremonial hall known for its expansive space, marble floors, chandeliers, and historic architecture.

You will also visit the legislative chambers of both houses — the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies — where laws are debated. Guided tours in Spanish and English are offered on most weekdays, though sessions may be canceled without notice if Parliament is in session.

Walking Tours in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Create Your Own Walk in Buenos Aires

Creating your own self-guided walk in Buenos Aires is easy and fun. Choose the city attractions that you want to see and a walk route map will be created just for you. You can even set your hotel as the start point of the walk.

Buenos Aires Introduction Walking Tour

Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, has a history marked by exploration, colonial rivalry, mass immigration, and political change. Its name derives from the Spanish dedication “Our Lady Saint Mary of the Good Air,” a title of the Virgin Mary venerated by sailors from Sardinia. The phrase “Buen Aire” originally referred to the clean, favorable winds near a sanctuary in the city of... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 4.7 Km or 2.9 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 4.7 Km or 2.9 Miles

Recoleta Neighborhood Walking Tour

One of Buenos Aires’ most beautiful neighborhoods, Recoleta is the city’s heart of art and elegance, grace and modernism, culture and leisure. Here you will find lots of things to do, like visiting museums, galleries and cultural centers; relaxing in one of the beautiful parks and plazas; or sampling the delicious local food.

This walking tour along Recoleta begins at the Ateneo Grand... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.4 Km or 2.1 Miles

This walking tour along Recoleta begins at the Ateneo Grand... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.4 Km or 2.1 Miles

Palermo Area Walking Tour

Situated just back from one of the main thoroughfares, Santa Fe Avenue (Avenida Santa Fe), Palermo is a relaxed and culturally delightful area full of restaurants, cafes, and wall murals. The tree-lined streets are shady and many of the older Spanish-style houses were converted into small shops without compromising their original character. It’s an excellent place in which to sample the city’s... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.5 Km or 2.2 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.5 Km or 2.2 Miles

Useful Travel Guides for Planning Your Trip

Top 5 Bars in San Telmo, Buenos Aires

With its cobbled streets, colonial era buildings and vibrant music and art scene, San Telmo is a great place to soak up the eclectic nature of Buenos Aires’ nightlife. The area boasts dozens of bars and cafes, with some of the city’s oldest lying next to the more modern. Indeed, San Telmo...

Top 7 Cafes in Palermo, Buenos Aires

The word "Palermo", believe it or not, may refer not just to Sicily, Italy, but also to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Indeed, this neighborhood (barrio) is largest in the city and is trendy and bohemian, renowned for its boutique shopping, cafes, restaurants, bars, and nightclubs. Oftentimes,...

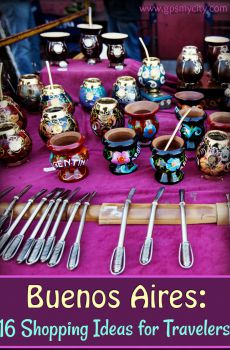

Buenos Aires: 16 Shopping Ideas for Travelers

Other than a cool place to be and a dream destination for many adventure-minded folk, Buenos Aires is a great culture hub where one can experience first-hand all that Argentina has to offer - great football, terrific wine, killer steaks, and much much more. This guide is to help you steer yourself...

Popular Palermo Restaurants, Buenos Aires

Although many visitors tend to think that Argentina is a meat and potatoes country, the rich cultural heritage from Italy, Spain, Portugal, and other European countries provide a veritable smorgasboard of dining options. Palermo is the barrio in Buenos Aires often referred to as 'The Restaurant...

The Most Popular Cities

/ view all