Malaga Introduction Walking Tour (Self Guided), Malaga

In 1325, the famed Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta reflected on his visit to Málaga, writing: "It is one of the largest and most beautiful towns of Andalusia, combining the conveniences of both sea and land.''

Málaga is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Europe, with a history spanning nearly three millennia. It was founded around the 8th century BC by Phoenician traders from Tyre, who established a settlement called Malaka. The name is generally linked to the Phoenician root "mlk'', a reference to the local production of salted fish and fermented fish sauce, or garum, which made the port economically valuable in antiquity.

Under Roman rule, Malaka became Malaca, a municipium within the province of Hispania Baetica. The city prospered as a commercial harbour, exporting fish products, wine, and olive oil across the Mediterranean. Roman Málaga left lasting physical traces, most notably the Roman Theatre at the foot of the Fortress hill, along with roads and infrastructure that connected the port to inland settlements.

After the decline of Roman authority, Málaga passed briefly through Visigothic hands before entering a long Islamic period following the Umayyad conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the early 8th century. The city flourished under Muslim rule, particularly between the 10th and 13th centuries, when its port, fortified walls, and shipyards supported trade with North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean.

In 1487, Málaga was captured by the Catholic Monarchs after a prolonged siege and incorporated into the expanding Kingdom of Castile.

During the modern period, the city remained an important port and experienced a renewed phase of growth driven by ironworks, textiles, and wine exports, while new boulevards and civic buildings reshaped its streetscape. Despite the economic challenges and upheavals of the 20th century, the late 20th and early 21st centuries saw Málaga re-emerge as a cultural and tourist destination.

Walking through Málaga’s historic centre today, you move between layers that sit unusually close together. The route leads past the Roman Theatre, where ancient stonework emerges at street level, before your gaze lifts toward the Malaga Fortress, whose walls still dominate the hillside above. Nearby, the Cathedral anchors the surrounding streets with its scale and pale stone. Between these landmarks, narrow lanes, small squares, and everyday cafes bind the city’s long history into the rhythm of daily life.

As you follow this walk, you can see it for yourself why Ibn Battuta’s words still resonate today.

Málaga is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Europe, with a history spanning nearly three millennia. It was founded around the 8th century BC by Phoenician traders from Tyre, who established a settlement called Malaka. The name is generally linked to the Phoenician root "mlk'', a reference to the local production of salted fish and fermented fish sauce, or garum, which made the port economically valuable in antiquity.

Under Roman rule, Malaka became Malaca, a municipium within the province of Hispania Baetica. The city prospered as a commercial harbour, exporting fish products, wine, and olive oil across the Mediterranean. Roman Málaga left lasting physical traces, most notably the Roman Theatre at the foot of the Fortress hill, along with roads and infrastructure that connected the port to inland settlements.

After the decline of Roman authority, Málaga passed briefly through Visigothic hands before entering a long Islamic period following the Umayyad conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the early 8th century. The city flourished under Muslim rule, particularly between the 10th and 13th centuries, when its port, fortified walls, and shipyards supported trade with North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean.

In 1487, Málaga was captured by the Catholic Monarchs after a prolonged siege and incorporated into the expanding Kingdom of Castile.

During the modern period, the city remained an important port and experienced a renewed phase of growth driven by ironworks, textiles, and wine exports, while new boulevards and civic buildings reshaped its streetscape. Despite the economic challenges and upheavals of the 20th century, the late 20th and early 21st centuries saw Málaga re-emerge as a cultural and tourist destination.

Walking through Málaga’s historic centre today, you move between layers that sit unusually close together. The route leads past the Roman Theatre, where ancient stonework emerges at street level, before your gaze lifts toward the Malaga Fortress, whose walls still dominate the hillside above. Nearby, the Cathedral anchors the surrounding streets with its scale and pale stone. Between these landmarks, narrow lanes, small squares, and everyday cafes bind the city’s long history into the rhythm of daily life.

As you follow this walk, you can see it for yourself why Ibn Battuta’s words still resonate today.

How it works: Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" from Apple App Store or Google Play Store to your mobile phone or tablet. The app turns your mobile device into a personal tour guide and its built-in GPS navigation functions guide you from one tour stop to next. The app works offline, so no data plan is needed when traveling abroad.

Malaga Introduction Walking Tour Map

Guide Name: Malaga Introduction Walking Tour

Guide Location: Spain » Malaga (See other walking tours in Malaga)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 13

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.4 Km or 2.1 Miles

Author: HelenF

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

Guide Location: Spain » Malaga (See other walking tours in Malaga)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 13

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.4 Km or 2.1 Miles

Author: HelenF

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

- Plaza y Acera de La Marina (Marina Square and Sidewalk)

- Mercado de Atarazanas (Shipyards Market)

- Calle Larios (Larios Street)

- Plaza de la Constitución (Constitution Square)

- Museo Carmen Thyssen Malaga (Carmen Thyssen Museum)

- Catedral de Málaga (Malaga Cathedral)

- Museo Picasso Málaga (Picasso Museum)

- Plaza de la Merced (Merced Square)

- Teatro Romano (Roman Theatre)

- Alcazaba of Malaga (Malaga Fortress)

- Parque de Malaga (Park of Malaga)

- Ayuntamiento de Málaga (Malaga City Hall)

- Castillo de Gibralfaro (Gibralfaro Castle)

1) Plaza y Acera de La Marina (Marina Square and Sidewalk)

Spanish sculptor Jaime Fernández Pimentel wanted to memorialize “Diego,” a cenachero—a traditional fish seller who carried baskets—who worked in front of Jaime’s childhood home on Carretería Street. Although cenacheros no longer exist, Jaime’s statue of Diego stands today as a lasting symbol of Málaga, located in Marina Square.

Marina Square and the adjoining waterfront promenade form part of Málaga’s long effort to reconnect the historic city with the sea. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, this stretch of coastline functioned primarily as a working port, separated from the urban centre by busy roads and port infrastructure. This changed in the early 21st century, when Málaga undertook a major redevelopment of its port front, transforming former docklands into open civic space.

Today, Marina Square acts as a natural transition point between the old city streets and the modern promenade. From here, wide pedestrian paths lead toward the sea, passing landscaped areas and shaded walkways. The promenade offers clear views back toward the city skyline, with the Alcazaba and Gibralfaro fortresses rising above the harbour, and outward toward the open bay.

The flat, spacious sidewalks make the square ideal for walking at a relaxed pace, while benches and palm-lined sections invite short pauses to watch the yachts, cruise ships, and the changing light over the bay. Public art installations and seasonal events occasionally animate the space.

Marina Square and the adjoining waterfront promenade form part of Málaga’s long effort to reconnect the historic city with the sea. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, this stretch of coastline functioned primarily as a working port, separated from the urban centre by busy roads and port infrastructure. This changed in the early 21st century, when Málaga undertook a major redevelopment of its port front, transforming former docklands into open civic space.

Today, Marina Square acts as a natural transition point between the old city streets and the modern promenade. From here, wide pedestrian paths lead toward the sea, passing landscaped areas and shaded walkways. The promenade offers clear views back toward the city skyline, with the Alcazaba and Gibralfaro fortresses rising above the harbour, and outward toward the open bay.

The flat, spacious sidewalks make the square ideal for walking at a relaxed pace, while benches and palm-lined sections invite short pauses to watch the yachts, cruise ships, and the changing light over the bay. Public art installations and seasonal events occasionally animate the space.

2) Mercado de Atarazanas (Shipyards Market) (must see)

When is a shipyard not a shipyard? When there are no ships, no yard, no water—and what you find instead is a market. The market’s name comes from Arabic, meaning “house of manufacture” or shipyard, referring to the Nasrid-era shipyards that once occupied this area during the Islamic period. When Málaga was under Muslim rule, this zone lay close to the shoreline and functioned as a centre for naval construction and repair. After the Christian conquest in the late 15th century, the shipyards gradually lost their original function, yet the name endured.

The present market building dates largely to the 19th century, when Málaga experienced an industrial boom. It incorporates iron architecture typical of the period, while preserving a key historical element: the monumental Nasrid marble gate that once formed part of the original shipyards. This gate, now integrated into the market’s façade, features carved vegetal motifs and stands as one of the few surviving architectural reminders of Málaga’s Islamic past within today’s urban fabric.

Inside the market, the spacious hall is organised into aisles of stalls selling fresh produce, seafood, meat, spices, and local specialities, offering a clear sense of Andalusian food culture. The stained-glass window above the main entrance depicts scenes from the city’s port and historic skyline. More than a place to shop, the market also functions as a lively social space where locals gather daily. And with its reputation for tapas, it’s easy to see why this is a popular meeting point.

The present market building dates largely to the 19th century, when Málaga experienced an industrial boom. It incorporates iron architecture typical of the period, while preserving a key historical element: the monumental Nasrid marble gate that once formed part of the original shipyards. This gate, now integrated into the market’s façade, features carved vegetal motifs and stands as one of the few surviving architectural reminders of Málaga’s Islamic past within today’s urban fabric.

Inside the market, the spacious hall is organised into aisles of stalls selling fresh produce, seafood, meat, spices, and local specialities, offering a clear sense of Andalusian food culture. The stained-glass window above the main entrance depicts scenes from the city’s port and historic skyline. More than a place to shop, the market also functions as a lively social space where locals gather daily. And with its reputation for tapas, it’s easy to see why this is a popular meeting point.

3) Calle Larios (Larios Street) (must see)

Larios Street is Málaga’s most prominent urban axis, created in the late 19th century as part of a major modernisation effort that reshaped the historic centre. Before its construction, this area was a dense network of narrow medieval streets prone to flooding and poor sanitation. The project was driven by the Larios family, influential industrialists and financiers. Opened in 1891, the street introduced a new sense of order and scale to the city, cutting a straight line between the port area and the heart of Málaga. Its uniform façades were inspired by Chicago-style commercial architecture.

From the outset, the street’s ground floors were reserved for shops and businesses, while the upper levels housed offices and select apartments. Over time, it became the city’s main commercial and social corridor, closely associated with public celebrations, processions, and everyday life. Today, it remains pedestrian-only and continues to serve as Málaga’s primary stage for major events, including Holy Week processions, the August Fair, and seasonal light installations that transform the street after dark.

Larios Street offers more than shopping, even if retail remains its primary function. Its gentle slope provides a clear visual link between the old town and the sea, while the consistent architectural rhythm makes it easy to appreciate the scale of the late 19th-century expansion. Stepping off the main avenue leads quickly into smaller streets, historic plazas, and nearby landmarks such as the cathedral and the central markets. As a result, Larios Street works both as a destination in itself and as a practical starting point for exploring Málaga’s historic centre.

From the outset, the street’s ground floors were reserved for shops and businesses, while the upper levels housed offices and select apartments. Over time, it became the city’s main commercial and social corridor, closely associated with public celebrations, processions, and everyday life. Today, it remains pedestrian-only and continues to serve as Málaga’s primary stage for major events, including Holy Week processions, the August Fair, and seasonal light installations that transform the street after dark.

Larios Street offers more than shopping, even if retail remains its primary function. Its gentle slope provides a clear visual link between the old town and the sea, while the consistent architectural rhythm makes it easy to appreciate the scale of the late 19th-century expansion. Stepping off the main avenue leads quickly into smaller streets, historic plazas, and nearby landmarks such as the cathedral and the central markets. As a result, Larios Street works both as a destination in itself and as a practical starting point for exploring Málaga’s historic centre.

4) Plaza de la Constitución (Constitution Square)

Constitution Square has long been one of Málaga’s central gathering places. Its origins lie in the medieval period, when the area functioned as an important open space within the Islamic city, close to markets and main routes. After the Christian conquest in 1487, the square assumed new roles under Castilian rule, becoming a setting for official proclamations, religious ceremonies, and public events.

The square took its current name in the 19th century, during Spain’s constitutional movements and periods of liberal reform. During this time, the surrounding buildings were reshaped with orderly façades, balconies, and arcades. Slightly off to one side stands the Fountain of Genoa, also known as the Fountain of Charles V. Brought to Málaga in the 17th century, this Italian-made fountain was acquired for nearly 1,000 ducats by the city authorities. A single gold ducat from the late 15th century is estimated to be worth several hundred US dollars today—do the math.

In more recent history, Constitution Square has adapted to changing urban needs. In 2002, it was pedestrianised together with nearby Larios Street, reinforcing its role as a public space. Each August, the square becomes a focal point of the Málaga Fair, which commemorates the 1487 conquest through the procession of the statue of the Virgin of Victory, traditionally associated with Queen Isabella. Holy Week processions and New Year celebrations also pass through the square. On ordinary days, cafés and shops line its edges, while the open centre offers a natural pause within Málaga’s historic centre.

The square took its current name in the 19th century, during Spain’s constitutional movements and periods of liberal reform. During this time, the surrounding buildings were reshaped with orderly façades, balconies, and arcades. Slightly off to one side stands the Fountain of Genoa, also known as the Fountain of Charles V. Brought to Málaga in the 17th century, this Italian-made fountain was acquired for nearly 1,000 ducats by the city authorities. A single gold ducat from the late 15th century is estimated to be worth several hundred US dollars today—do the math.

In more recent history, Constitution Square has adapted to changing urban needs. In 2002, it was pedestrianised together with nearby Larios Street, reinforcing its role as a public space. Each August, the square becomes a focal point of the Málaga Fair, which commemorates the 1487 conquest through the procession of the statue of the Virgin of Victory, traditionally associated with Queen Isabella. Holy Week processions and New Year celebrations also pass through the square. On ordinary days, cafés and shops line its edges, while the open centre offers a natural pause within Málaga’s historic centre.

5) Museo Carmen Thyssen Malaga (Carmen Thyssen Museum) (must see)

The Carmen Thyssen Museum occupies the restored Villalón Palace, a 16th-century noble residence in Málaga’s historic centre, and represents a key chapter in the city’s cultural renewal. The palace incorporates Renaissance elements alongside earlier remains uncovered during restoration, including traces of Roman and Islamic occupation. The museum opened in 2011, following an agreement between the city and Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza, whose private collection forms the core of the institution. Its creation marked a shift in Málaga’s identity, reinforcing its move from a port-centred economy toward a city invested in art and heritage.

The collection focuses primarily on Spanish painting of the 19th and early 20th centuries, with a strong emphasis on Andalusia. Works by artists such as Darío de Regoyos, Joaquín Sorolla, and Julio Romero de Torres explore themes of landscape, daily life, tradition, and regional identity. Rather than presenting a broad survey of European art, the museum offers a concentrated look at how Spanish painters responded to social change, modernity, and local customs, making it especially relevant to understanding southern Spain’s cultural history.

The museum combines art and setting in a compact, approachable format. The galleries are clearly organised, allowing for an easy flow through the collection, while temporary exhibitions add variety for repeat visits. The interior courtyard and surrounding streets provide a quiet contrast to the busier commercial areas nearby, making the museum both a cultural stop and a moment of pause.

The site is also archaeologically significant. Excavations carried out since 2005 have unearthed Roman-era remains, offering insight into continuous occupation from the 1st to the 5th century AD. Highlights include a suburban villa with a fish-salting factory, a monumental nymphaeum adorned with fish-themed wall paintings, geometric mosaics, and fragments of a bronze sculpture. The area later experienced periods of abandonment, a brief revival of fish production in the 5th century, and eventual use as a necropolis during the Byzantine era.

The collection focuses primarily on Spanish painting of the 19th and early 20th centuries, with a strong emphasis on Andalusia. Works by artists such as Darío de Regoyos, Joaquín Sorolla, and Julio Romero de Torres explore themes of landscape, daily life, tradition, and regional identity. Rather than presenting a broad survey of European art, the museum offers a concentrated look at how Spanish painters responded to social change, modernity, and local customs, making it especially relevant to understanding southern Spain’s cultural history.

The museum combines art and setting in a compact, approachable format. The galleries are clearly organised, allowing for an easy flow through the collection, while temporary exhibitions add variety for repeat visits. The interior courtyard and surrounding streets provide a quiet contrast to the busier commercial areas nearby, making the museum both a cultural stop and a moment of pause.

The site is also archaeologically significant. Excavations carried out since 2005 have unearthed Roman-era remains, offering insight into continuous occupation from the 1st to the 5th century AD. Highlights include a suburban villa with a fish-salting factory, a monumental nymphaeum adorned with fish-themed wall paintings, geometric mosaics, and fragments of a bronze sculpture. The area later experienced periods of abandonment, a brief revival of fish production in the 5th century, and eventual use as a necropolis during the Byzantine era.

6) Catedral de Málaga (Malaga Cathedral) (must see)

Málaga Cathedral stands at the heart of the historic centre and reflects the city’s transition from Islamic rule to Christian Spain. Construction began in 1528 on the site of the former Great Mosque, following the Christian conquest of the city in 1487. Built over more than two centuries, the cathedral brings together several architectural phases, with a predominantly Renaissance structure later enriched by Baroque elements. The project was never fully completed, a circumstance that earned it the nickname “the One-Armed Lady,” referring to the unfinished south tower. A plaque near the truncated tower explains why: funds originally intended for its completion were diverted in the late 18th century to support the American revolutionaries, a transfer facilitated by Luis de Unzaga, then governor of what is now Louisiana, through his connections to King Carlos III of Spain. As a result, the cathedral has remained “short-armed” since at least 1782.

The main façade differs from the rest of the building because of its pronounced Baroque character. Arranged on two levels, it features three large arches on the lower tier, with portals flanked by marble columns. Above them, medallions depict Málaga’s patron saints, Cyriacus and Paula, alongside a representation of the Annunciation.

Once you step inside the main nave, head toward the centre of the church to find the choir stalls. They are located in the central aisle, between the main entrance and the high altar. The sculptural works feature 42 intricately carved wooden figures of saints and religious subjects. Most of the seats were carved in the 17th century, and their craftsmanship is unique. Take a moment to notice the small ledges beneath the seats, used as misericords for leaning during long services.

Another cathedral highlight is the twin organs. As you face the choir stalls, look to your left and right—the two organs flank the choir. These massive, 18th-century Epistle and Gospel organs contain over 10,000 pipes combined. They are rare for their perfect symmetry and are still used for concerts today.

The experience extends beyond the nave. Access to the roof offers broad views across the old town, the port, and the Alcazaba. Roof access is available only via guided tour, and the staircase leading to the roof can be reached from the Orange Tree Courtyard, located north of the cathedral.

Editor’s note: The cathedral’s rooftop visits are suspended until 2027, due to repair works being carried out on the roof.

The main façade differs from the rest of the building because of its pronounced Baroque character. Arranged on two levels, it features three large arches on the lower tier, with portals flanked by marble columns. Above them, medallions depict Málaga’s patron saints, Cyriacus and Paula, alongside a representation of the Annunciation.

Once you step inside the main nave, head toward the centre of the church to find the choir stalls. They are located in the central aisle, between the main entrance and the high altar. The sculptural works feature 42 intricately carved wooden figures of saints and religious subjects. Most of the seats were carved in the 17th century, and their craftsmanship is unique. Take a moment to notice the small ledges beneath the seats, used as misericords for leaning during long services.

Another cathedral highlight is the twin organs. As you face the choir stalls, look to your left and right—the two organs flank the choir. These massive, 18th-century Epistle and Gospel organs contain over 10,000 pipes combined. They are rare for their perfect symmetry and are still used for concerts today.

The experience extends beyond the nave. Access to the roof offers broad views across the old town, the port, and the Alcazaba. Roof access is available only via guided tour, and the staircase leading to the roof can be reached from the Orange Tree Courtyard, located north of the cathedral.

Editor’s note: The cathedral’s rooftop visits are suspended until 2027, due to repair works being carried out on the roof.

7) Museo Picasso Málaga (Picasso Museum) (must see)

The Picasso Museum is rooted directly in the city where Pablo Picasso was born in 1881 and occupies the Buenavista Palace, a 16th-century aristocratic residence in Málaga’s historic centre.

Picasso’s father, José Ruiz, served as curator of Málaga’s city museum, which operated under tight budgets and was rarely open to the public. As part of his compensation, Ruiz was granted exclusive use of a room as an art studio, where the young Pablo made his earliest sketches under his father’s guidance. Although Picasso would later be represented by major museums in Paris and Barcelona, the Málaga museum holds particular significance: it stands only a short walk from Merced Square, where he was born.

The idea of establishing a Picasso museum in Málaga circulated for decades before becoming a reality in the early 21st century, driven by the artist’s family. The museum opened in 2003, following a substantial donation of works from Christine and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, with the official inauguration attended by the King and Queen of Spain.

Rather than concentrating on a single period, the collection traces Picasso’s artistic evolution across his entire career. Typically organised chronologically across 11 galleries, it begins with Picasso’s early academic works, led by the 1895 painting Portrait of a Bearded Man. The rooms dedicated to his Neoclassical period contain one of the museum’s crown jewels—the 1923 painting The Three Graces. Toward the end of the circuit, visitors encounter Picasso’s works from the 1970s, which are noticeably more colourful and expressive. Temporary exhibitions regularly place the artist’s work in dialogue with other creators and themes.

Beneath the palace lie archaeological remains, including partially preserved structures from a Nasrid palace alongside earlier Roman traces. Visitors can walk on glass walkways over 2,500-year-old city walls and the remains of a Roman fish-salting factory. One of the main highlights of the basement level is the Phoenician wall dating from the 7th and 8th centuries BC. The archaeological site is accessible via staircases or an elevator.

The institution also houses an archive of documents and photographs, as well as a specialised library containing more than 14,000 titles devoted to Picasso.

Picasso’s father, José Ruiz, served as curator of Málaga’s city museum, which operated under tight budgets and was rarely open to the public. As part of his compensation, Ruiz was granted exclusive use of a room as an art studio, where the young Pablo made his earliest sketches under his father’s guidance. Although Picasso would later be represented by major museums in Paris and Barcelona, the Málaga museum holds particular significance: it stands only a short walk from Merced Square, where he was born.

The idea of establishing a Picasso museum in Málaga circulated for decades before becoming a reality in the early 21st century, driven by the artist’s family. The museum opened in 2003, following a substantial donation of works from Christine and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, with the official inauguration attended by the King and Queen of Spain.

Rather than concentrating on a single period, the collection traces Picasso’s artistic evolution across his entire career. Typically organised chronologically across 11 galleries, it begins with Picasso’s early academic works, led by the 1895 painting Portrait of a Bearded Man. The rooms dedicated to his Neoclassical period contain one of the museum’s crown jewels—the 1923 painting The Three Graces. Toward the end of the circuit, visitors encounter Picasso’s works from the 1970s, which are noticeably more colourful and expressive. Temporary exhibitions regularly place the artist’s work in dialogue with other creators and themes.

Beneath the palace lie archaeological remains, including partially preserved structures from a Nasrid palace alongside earlier Roman traces. Visitors can walk on glass walkways over 2,500-year-old city walls and the remains of a Roman fish-salting factory. One of the main highlights of the basement level is the Phoenician wall dating from the 7th and 8th centuries BC. The archaeological site is accessible via staircases or an elevator.

The institution also houses an archive of documents and photographs, as well as a specialised library containing more than 14,000 titles devoted to Picasso.

8) Plaza de la Merced (Merced Square) (must see)

Merced Square is one of Málaga’s oldest and most historically charged public spaces and forms the heart of the La Merced neighbourhood. Located just outside the former Moorish city walls, it functioned early on as an open civic space. In August 1487, it became the stage for a defining moment in the city’s history: the formal surrender of Málaga by its Muslim rulers. The ceremony unfolded as a grand procession led by Bishop Pedro de Toledo, accompanied by the Catholic Monarchs, knights, nobility, and freed Christian captives.

In 1507, the square took on a new identity with the arrival of the Mercedarian friars, whose mission was the redemption of Christian captives. They built a church and a large convent that gave the square its enduring name and anchored it as a religious and social centre. Over the following centuries, Merced Square evolved into a residential and civic space, framed by houses, institutions, and places of gathering.

At its centre stands a 19th-century obelisk commemorating Spanish liberal soldier General José María Torrijos and his companions, executed in 1831 for their opposition to absolutist rule. Beneath the monument lies a crypt containing their remains. While the crypt is not open to the public, the names of the fallen are inscribed on the pedestal.

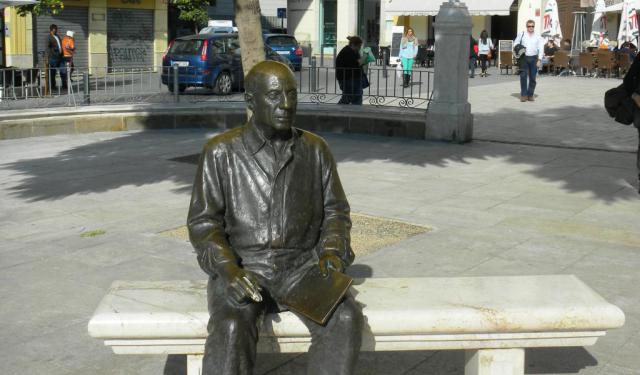

Merced Square is also closely tied to Pablo Picasso. He was born in 1881 at number 15 at the northern corner of the square, a building that now houses a museum and the headquarters of the Pablo Ruiz Picasso Foundation. Additionally, the northern corner of the square hosts a bronze statue of Picasso seated on a bench with notebook and pencil in hand, leaving space beside him for visitors. The marble bench and the statue can be found right in front of the square's northern access point.

Today, cafés and terraces line the perimeter, making the square a lively meeting point.

In 1507, the square took on a new identity with the arrival of the Mercedarian friars, whose mission was the redemption of Christian captives. They built a church and a large convent that gave the square its enduring name and anchored it as a religious and social centre. Over the following centuries, Merced Square evolved into a residential and civic space, framed by houses, institutions, and places of gathering.

At its centre stands a 19th-century obelisk commemorating Spanish liberal soldier General José María Torrijos and his companions, executed in 1831 for their opposition to absolutist rule. Beneath the monument lies a crypt containing their remains. While the crypt is not open to the public, the names of the fallen are inscribed on the pedestal.

Merced Square is also closely tied to Pablo Picasso. He was born in 1881 at number 15 at the northern corner of the square, a building that now houses a museum and the headquarters of the Pablo Ruiz Picasso Foundation. Additionally, the northern corner of the square hosts a bronze statue of Picasso seated on a bench with notebook and pencil in hand, leaving space beside him for visitors. The marble bench and the statue can be found right in front of the square's northern access point.

Today, cafés and terraces line the perimeter, making the square a lively meeting point.

9) Teatro Romano (Roman Theatre)

The Roman Theatre of Málaga is one of the city’s most important archaeological remains and a clear reminder of its Roman past. It was built in the early 1st century AD, during the reign of Emperor Augustus, when Málaga was a prosperous Roman municipium within the province of Hispania Baetica. Set at the foot of the Alcazaba hill, close to the ancient harbour, the theatre hosted dramatic performances and public gatherings. The seating area was carefully integrated into the slope of the hillside: the semicircular enclosure has a radius of about 31 metres, reaches a height of roughly 16 metres, and is divided by aisles to organise spectators. In front of it lies the orchestra, a semicircular space about 15 metres wide where performances were staged.

After the decline of Roman rule, the theatre gradually fell out of use and was buried beneath later structures. During the Islamic period, some of its stone was reused in the construction of the Alcazaba above, and in the 20th century the site was covered by a cultural centre. The theatre came back to light only in 1951, during redevelopment works, prompting systematic excavations that revealed its overall form, including seating tiers, sections of the stage, and surviving fragments of original walls. Much of what visitors see today is a careful reconstruction that outlines the ancient structure. Excavation is still ongoing, and signs of a larger Roman complex around the theatre continue to emerge.

A modern interpretation centre, inaugurated in 2010, offers audiovisual presentations explaining Roman Málaga and displaying objects uncovered during excavations.

After the decline of Roman rule, the theatre gradually fell out of use and was buried beneath later structures. During the Islamic period, some of its stone was reused in the construction of the Alcazaba above, and in the 20th century the site was covered by a cultural centre. The theatre came back to light only in 1951, during redevelopment works, prompting systematic excavations that revealed its overall form, including seating tiers, sections of the stage, and surviving fragments of original walls. Much of what visitors see today is a careful reconstruction that outlines the ancient structure. Excavation is still ongoing, and signs of a larger Roman complex around the theatre continue to emerge.

A modern interpretation centre, inaugurated in 2010, offers audiovisual presentations explaining Roman Málaga and displaying objects uncovered during excavations.

10) Alcazaba of Malaga (Malaga Fortress) (must see)

The Málaga Fortress, commonly known as the Alcazaba, is a defining reminder of the city’s Islamic past. Built in the 11th century during Muslim rule in al-Andalus, it functioned both as a military stronghold and as a residence for governors. Its commanding position above the old city and port allowed control over maritime traffic and inland routes. The complex was expanded and reinforced over time, particularly under the Nasrid dynasty, before being taken by the Catholic Monarchs in 1487 after one of the longest sieges of the Reconquest. King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I entered the fortress and raised their royal standard on the Tower of Tribute, a moment often cited as a turning point in the formation of unified Spain.

The fortress is organised as a carefully layered defensive system. Access to the outer enclosure is gained through the Vault Gate, designed with a sharp double-back turn intended to slow and expose intruders—though today visitors can bypass this ascent using an elevator located on Guillén Sotelo Street, behind the City Hall. From the Vault Gate, a rising path leads past gardens and ornate fountains to the Gate of Columns. After passing through the Gate of Columns, the path opens to the left toward the Christ Gate. Once through this gate, you enter the Parade Ground. Here, on the opposite side of the Christ Gate, the Gate of the Granada Quarters leads toward the palatial heart of the Alcazaba.

Beyond the Gate of the Granada Quarters lies the Courtyard of the Jets. On the western side of the courtyard, the 11th-century Taifa Palace comes into view. Its defining feature is the Southern Pavilion, which displays Caliphal-style horseshoe arches of particular elegance.

Moving to the northwestern side of the Courtyard of the Jets brings you into the Orange Tree Courtyard—a quiet space that once served as the entrance hall to the palaces. Continuing north, you encounter the more delicate architecture of the 13th-century Nasrid period. This section is centred around the Pool Palace, where a long reflecting pool and finely carved plaster arches define the space. The rooms surrounding this courtyard now house a small Archaeological Museum, displaying Moorish ceramics and artefacts uncovered during excavations.

The fortress is organised as a carefully layered defensive system. Access to the outer enclosure is gained through the Vault Gate, designed with a sharp double-back turn intended to slow and expose intruders—though today visitors can bypass this ascent using an elevator located on Guillén Sotelo Street, behind the City Hall. From the Vault Gate, a rising path leads past gardens and ornate fountains to the Gate of Columns. After passing through the Gate of Columns, the path opens to the left toward the Christ Gate. Once through this gate, you enter the Parade Ground. Here, on the opposite side of the Christ Gate, the Gate of the Granada Quarters leads toward the palatial heart of the Alcazaba.

Beyond the Gate of the Granada Quarters lies the Courtyard of the Jets. On the western side of the courtyard, the 11th-century Taifa Palace comes into view. Its defining feature is the Southern Pavilion, which displays Caliphal-style horseshoe arches of particular elegance.

Moving to the northwestern side of the Courtyard of the Jets brings you into the Orange Tree Courtyard—a quiet space that once served as the entrance hall to the palaces. Continuing north, you encounter the more delicate architecture of the 13th-century Nasrid period. This section is centred around the Pool Palace, where a long reflecting pool and finely carved plaster arches define the space. The rooms surrounding this courtyard now house a small Archaeological Museum, displaying Moorish ceramics and artefacts uncovered during excavations.

11) Parque de Malaga (Park of Malaga) (must see)

Málaga Park was created in the late 19th century as part of the city’s broader effort to modernise and improve public spaces. It occupies land reclaimed from the sea after port expansions, transforming what had once been shoreline into a landscaped green corridor between the historic centre and the harbour. Conceived as both a botanical garden and a place for leisure, the park reflected contemporary ideas about urban health, order, and civic pride.

The park is laid out as a long promenade running through its centre, flanked on either side by formal garden areas inspired by Baroque and Renaissance design. Wide paths, fountains, and carefully planned plantings define the space, while benches decorated with Sevillian tiles add a distinctive local touch. Its subtropical character is one of its defining features, with palms, ficus trees, jacarandas, and many exotic species introduced from different parts of the world. In total, the park covers approximately 30,000 square feet, incorporating the rose garden, the tree-lined areas near the City Hall, and the gardens of the Dark Gate.

Málaga Park offers a welcome pause from the surrounding streets. Shaded walkways provide relief from the heat, benches invite short rests, and monuments and sculptures dedicated to writers, politicians, and local figures appear along the route. Rather than focusing on a single landmark, the park functions as a connective space, allowing anyone to experience a slower, greener side of Málaga while moving naturally between the historic centre and the sea.

The park is laid out as a long promenade running through its centre, flanked on either side by formal garden areas inspired by Baroque and Renaissance design. Wide paths, fountains, and carefully planned plantings define the space, while benches decorated with Sevillian tiles add a distinctive local touch. Its subtropical character is one of its defining features, with palms, ficus trees, jacarandas, and many exotic species introduced from different parts of the world. In total, the park covers approximately 30,000 square feet, incorporating the rose garden, the tree-lined areas near the City Hall, and the gardens of the Dark Gate.

Málaga Park offers a welcome pause from the surrounding streets. Shaded walkways provide relief from the heat, benches invite short rests, and monuments and sculptures dedicated to writers, politicians, and local figures appear along the route. Rather than focusing on a single landmark, the park functions as a connective space, allowing anyone to experience a slower, greener side of Málaga while moving naturally between the historic centre and the sea.

12) Ayuntamiento de Málaga (Malaga City Hall)

Málaga City Hall stands at the eastern edge of the historic centre, marking the transition between the old town and the parklands along the waterfront. Completed in 1919 during a period of civic optimism, the building reflects the city’s desire to project confidence and modernity through public architecture. Designed in an eclectic style, the City Hall combines Neoclassical symmetry with Baroque and regional decorative elements. The structure rises over three floors and is crowned by a central clock tower, while the façade is richly adorned with sculpted male figures and garlands of fruits and vegetables.

The interior contains a wealth of decorative features, including a prominent sculpture of a woman personifying the city of Málaga, surrounded by allegorical figures representing architecture, commerce, fishing, and the sea. On the first floor, stained-glass windows illustrate key moments from Málaga’s history, filtering coloured light into the ceremonial spaces. The second floor houses the mayor’s offices, the council meeting room, and the celebrated Hall of Mirrors, the most recognisable interior space. Here, Neo-Rococo mirror frames line the walls, while the ceiling features paintings by well-known artists. The surrounding corridors display painted portraits of Málaga’s 20th-century mayors.

Although Málaga City Hall remains an active administrative centre, visitors can enter only with special permission.

The interior contains a wealth of decorative features, including a prominent sculpture of a woman personifying the city of Málaga, surrounded by allegorical figures representing architecture, commerce, fishing, and the sea. On the first floor, stained-glass windows illustrate key moments from Málaga’s history, filtering coloured light into the ceremonial spaces. The second floor houses the mayor’s offices, the council meeting room, and the celebrated Hall of Mirrors, the most recognisable interior space. Here, Neo-Rococo mirror frames line the walls, while the ceiling features paintings by well-known artists. The surrounding corridors display painted portraits of Málaga’s 20th-century mayors.

Although Málaga City Hall remains an active administrative centre, visitors can enter only with special permission.

13) Castillo de Gibralfaro (Gibralfaro Castle) (must see)

Gibralfaro Castle rises above Málaga on a hill that reaches about 131 metres in height, overlooking the city, the port, and the Mediterranean Sea. Built in the mid-14th century during the Nasrid period, the fortress was intended to reinforce the defence of the Alcazaba below and to control both land and sea approaches. The site held strategic importance long before the castle itself: the Moors erected the fortress near an earlier lighthouse constructed by the Phoenicians. Its name reflects this layered history, combining the Arabic word gabel, meaning “rock,” with the Greek word faro, meaning “lighthouse.” Today, the castle’s silhouette is so closely tied to the city that it appears on the official seal and flag of Málaga.

The fortress played a decisive role during the Reconquest. In 1487, the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella laid siege to Gibralfaro for three months. The stronghold resisted until hunger forced the Moorish garrison to surrender. Notably, this siege marked the first time that both attacking and defending armies made use of gunpowder, signalling a turning point in warfare. After the conquest, the castle remained under Christian control, although its military importance gradually declined.

Gibralfaro Castle offers insight into both military life and daily survival within a fortress. After passing through the main gate, you encounter the former gunpowder magazine immediately to your left. Today, it houses a small military museum displaying uniforms, weapons, and a detailed model of the city during the Islamic period. Exiting the museum and continuing straight ahead brings you to the Upper Courtyard. One of its key features is the Airon Well, carved roughly 40 metres into solid rock during the Phoenician era. The well is easy to identify by its small, rounded fountain head rising about one metre above the ground. Nearby stands the Main Tower, approximately 17 metres tall, which can be accessed from the southeastern part of the courtyard.

Arguably, the castle’s greatest attraction is its ramparts. Visitors can climb onto them and walk the full perimeter of the battlements. Although staircases throughout the complex provide access to the walls, the most effective route begins at the top of the Main Tower. From there, walking clockwise along the walls ensures that no viewpoints are missed. The panoramic views take in the Port of Málaga, the Alcazaba below, and Málaga Cathedral, offering one of the most comprehensive outlooks in the city.

The fortress played a decisive role during the Reconquest. In 1487, the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella laid siege to Gibralfaro for three months. The stronghold resisted until hunger forced the Moorish garrison to surrender. Notably, this siege marked the first time that both attacking and defending armies made use of gunpowder, signalling a turning point in warfare. After the conquest, the castle remained under Christian control, although its military importance gradually declined.

Gibralfaro Castle offers insight into both military life and daily survival within a fortress. After passing through the main gate, you encounter the former gunpowder magazine immediately to your left. Today, it houses a small military museum displaying uniforms, weapons, and a detailed model of the city during the Islamic period. Exiting the museum and continuing straight ahead brings you to the Upper Courtyard. One of its key features is the Airon Well, carved roughly 40 metres into solid rock during the Phoenician era. The well is easy to identify by its small, rounded fountain head rising about one metre above the ground. Nearby stands the Main Tower, approximately 17 metres tall, which can be accessed from the southeastern part of the courtyard.

Arguably, the castle’s greatest attraction is its ramparts. Visitors can climb onto them and walk the full perimeter of the battlements. Although staircases throughout the complex provide access to the walls, the most effective route begins at the top of the Main Tower. From there, walking clockwise along the walls ensures that no viewpoints are missed. The panoramic views take in the Port of Málaga, the Alcazaba below, and Málaga Cathedral, offering one of the most comprehensive outlooks in the city.

Walking Tours in Malaga, Spain

Create Your Own Walk in Malaga

Creating your own self-guided walk in Malaga is easy and fun. Choose the city attractions that you want to see and a walk route map will be created just for you. You can even set your hotel as the start point of the walk.

Architectural Jewels of Malaga

The blooming port city of Málaga has a wealth of architecture with no shortage of ancient and otherwise impressive buildings fit to vow any visitor. Having witnessed the fall and rise of many civilizations, Malaga's uniqueness is marked by the variety of architectural styles, upon which the times past had a great deal of impact. From its stunning Moorish fortress – the best-preserved of... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Pablo Picasso's Malaga

Among other things for which Malaga has gone down in history is being the town where Pablo Picasso, the famous painter and innovator of the Cubist movement, was born and spent his early childhood. The milieu and the daily life of those years inspired some of Picasso’s most characteristic subjects in paintings, such as flamenco, doves and bulls.

The best place to start a walk through... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.3 Km or 0.8 Miles

The best place to start a walk through... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.3 Km or 0.8 Miles

Useful Travel Guides for Planning Your Trip

5 Best Shopping Streets in Malaga, Spain

As well as one of the best cultural destinations in southern Spain, Malaga turns out to be something of a shopping mecca. Along with the ubiquitous shopping malls on the outskirts, the capital of Costa del Sol has managed to preserve its network of specialist shops, difficult to find in most big...

The Most Popular Cities

/ view all