Pablo Picasso's Malaga (Self Guided), Malaga

According to a well-known story, Picasso’s first word was “piz,” a child’s attempt at “lápiz,” meaning “pencil.”

Málaga at the end of the 19th century was a busy Mediterranean port. When Pablo Ruiz Picasso was born here in 1881, the city was neither a bohemian art capital nor a provincial backwater, but a working, outward-looking place where commerce, craftsmanship, and popular culture intersected.

Picasso’s family was firmly embedded in this urban fabric. His father, José Ruiz Blasco, was a painter, art teacher, and curator at the city museum. Though modestly funded, the institution exposed the young Picasso to academic drawing, classical models, and religious imagery from an early age. Málaga’s Holy Week processions, popular festivals, bullfights, and the vivid street life of the historic centre all shaped his early artistic awareness.

The city itself offered constant contrasts, ranging from ancient ruins to 19th-century boulevards. Picasso absorbed this layered environment intuitively. Although he left Málaga as a child—moving first to La Coruña and later to Barcelona—the city remained psychologically significant.

For much of the 20th century, Málaga played a surprisingly minor role in Picasso’s public narrative. His fame became associated with Paris, Barcelona, and later the south of France. Only toward the end of the century did Málaga begin to reclaim Picasso as a central figure in its own story, culminating in the opening of the Picasso Museum Málaga in 2003, housed in the Buenavista Palace, just steps from his birthplace at Merced Square.

Walking through Picasso’s Málaga leads you from Merced Square to the Picasso Birthplace Museum, past his seated statue quietly observing the square. A short walk brings you to the Church of Santiago Apóstol, where he was baptised, before the route continues toward the Picasso Museum. Along the way, everyday streets and small plazas reveal how Picasso’s early life was woven into the ordinary rhythms of the city.

It is safe to say that Picasso's legacy still echoes throughout Malaga. Take on this adventure and see for yourself how the city made him pick up the pencil for the first time. It never really left his hand after that.

Málaga at the end of the 19th century was a busy Mediterranean port. When Pablo Ruiz Picasso was born here in 1881, the city was neither a bohemian art capital nor a provincial backwater, but a working, outward-looking place where commerce, craftsmanship, and popular culture intersected.

Picasso’s family was firmly embedded in this urban fabric. His father, José Ruiz Blasco, was a painter, art teacher, and curator at the city museum. Though modestly funded, the institution exposed the young Picasso to academic drawing, classical models, and religious imagery from an early age. Málaga’s Holy Week processions, popular festivals, bullfights, and the vivid street life of the historic centre all shaped his early artistic awareness.

The city itself offered constant contrasts, ranging from ancient ruins to 19th-century boulevards. Picasso absorbed this layered environment intuitively. Although he left Málaga as a child—moving first to La Coruña and later to Barcelona—the city remained psychologically significant.

For much of the 20th century, Málaga played a surprisingly minor role in Picasso’s public narrative. His fame became associated with Paris, Barcelona, and later the south of France. Only toward the end of the century did Málaga begin to reclaim Picasso as a central figure in its own story, culminating in the opening of the Picasso Museum Málaga in 2003, housed in the Buenavista Palace, just steps from his birthplace at Merced Square.

Walking through Picasso’s Málaga leads you from Merced Square to the Picasso Birthplace Museum, past his seated statue quietly observing the square. A short walk brings you to the Church of Santiago Apóstol, where he was baptised, before the route continues toward the Picasso Museum. Along the way, everyday streets and small plazas reveal how Picasso’s early life was woven into the ordinary rhythms of the city.

It is safe to say that Picasso's legacy still echoes throughout Malaga. Take on this adventure and see for yourself how the city made him pick up the pencil for the first time. It never really left his hand after that.

How it works: Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" from Apple App Store or Google Play Store to your mobile phone or tablet. The app turns your mobile device into a personal tour guide and its built-in GPS navigation functions guide you from one tour stop to next. The app works offline, so no data plan is needed when traveling abroad.

Pablo Picasso's Malaga Map

Guide Name: Pablo Picasso's Malaga

Guide Location: Spain » Malaga (See other walking tours in Malaga)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 6

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.3 Km or 0.8 Miles

Author: HelenF

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

Guide Location: Spain » Malaga (See other walking tours in Malaga)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 6

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.3 Km or 0.8 Miles

Author: HelenF

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

- Picasso Birthplace Museum

- Estatua de Pablo Ruiz Picasso (Picasso Sculpture)

- Iglesia de Santiago Apóstol (Church of Santiago Apostol)

- Museo Picasso Málaga (Picasso Museum)

- Convento de San Agustín de Málaga (San Agustín Convent)

- Centro Cultural La Malagueta (La Malagueta Cultural Center)

1) Picasso Birthplace Museum

The Picasso Birthplace Museum occupies the modest 19th-century building on Merced Square where Pablo Picasso was born in 1881 and spent his earliest years. The house was erected in 1861, and Picasso’s father, José Ruiz Blasco, rented the first-floor apartment between 1880 and 1883. The interior reflects the everyday setting of a middle-class household in late-19th-century Málaga.

The building was declared a Historic-Artistic Monument of National Interest in 1983 and later taken over by the Picasso Foundation. After restoration, it officially reopened in 1998, with the King and Queen of Spain in attendance.

Inside, the museum is organised across several levels. Upon entering, turn left to reach the ground-floor exhibition hall, which presents objects from Picasso’s early family life alongside works by both Picasso and his father. Ruiz Blasco, a painter and art teacher, played a decisive role in his son’s first artistic training. One of the highlights is a sketchbook—the only one of its kind in Spain—containing preparatory studies for "The Ladies of Avignon''. It marks a pivotal moment when Picasso began his path toward modern art. You can explore the entire album page by page on a digital screen.

Climbing the stairs to the first floor, you will find Room 6, where a display case holds intimate childhood items, including Picasso’s umbilical sash, his baptismal garment, and the lead figurines he played with in this very building. Nearby, Room 9 exhibits an exact replica of the Spanish cape gifted to him by his close friend and barber, Eugenio Arias—a garment so meaningful that Picasso chose to be buried in it. A QR code allows visitors to hear a rare recorded interview in which Picasso speaks Spanish and reflects on his longing for his homeland.

The upper level houses the library and Research Centre, with an extensive archive devoted to Picasso and his work. Beyond Picasso’s own prints, ceramics, and graphic pieces, the museum also preserves a wider collection of around 3,500 works by some 200 artists, including Miró, Christo, Bacon, Brossa, Ernst, and Málaga-based artists from the 1950s to the present.

The building was declared a Historic-Artistic Monument of National Interest in 1983 and later taken over by the Picasso Foundation. After restoration, it officially reopened in 1998, with the King and Queen of Spain in attendance.

Inside, the museum is organised across several levels. Upon entering, turn left to reach the ground-floor exhibition hall, which presents objects from Picasso’s early family life alongside works by both Picasso and his father. Ruiz Blasco, a painter and art teacher, played a decisive role in his son’s first artistic training. One of the highlights is a sketchbook—the only one of its kind in Spain—containing preparatory studies for "The Ladies of Avignon''. It marks a pivotal moment when Picasso began his path toward modern art. You can explore the entire album page by page on a digital screen.

Climbing the stairs to the first floor, you will find Room 6, where a display case holds intimate childhood items, including Picasso’s umbilical sash, his baptismal garment, and the lead figurines he played with in this very building. Nearby, Room 9 exhibits an exact replica of the Spanish cape gifted to him by his close friend and barber, Eugenio Arias—a garment so meaningful that Picasso chose to be buried in it. A QR code allows visitors to hear a rare recorded interview in which Picasso speaks Spanish and reflects on his longing for his homeland.

The upper level houses the library and Research Centre, with an extensive archive devoted to Picasso and his work. Beyond Picasso’s own prints, ceramics, and graphic pieces, the museum also preserves a wider collection of around 3,500 works by some 200 artists, including Miró, Christo, Bacon, Brossa, Ernst, and Málaga-based artists from the 1950s to the present.

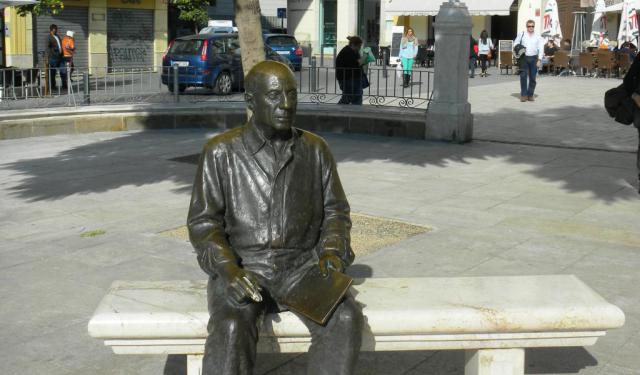

2) Estatua de Pablo Ruiz Picasso (Picasso Sculpture)

The Picasso Sculpture is a bronze statue located in Merced Square, where Pablo Picasso was born in 1881. Created by Spanish sculptor Francisco López Hernández and inaugurated on December 5, 2008, the monument forms part of Málaga’s broader effort to reconnect Picasso’s international legacy with his birthplace. The figure is almost life-size, slightly larger than Picasso’s actual stature.

Rather than presenting Picasso as a distant or heroic figure, the sculpture shows him seated casually on a bench, notebook and pencil in hand, dressed simply and appearing relaxed. The statue’s approachable scale and informal pose encourage interaction. The bench extends beyond the figure, leaving enough space for visitors to sit beside him.

Since its installation, the sculpture has become an active participant in the life of Merced Square. It regularly features in public performances and cultural events held in the square, including the annual White Night, celebrated since 2009, during which the statue is often decorated to match the event’s theme.

In April 2013, the statue became the centre of an unusual episode when a group of vandals attempted to steal it. The attempt failed due to the sculpture’s weight, and it was abandoned on a nearby bench.

Today, the statue has returned to its usual spot. You are free to sit beside Picasso, have a chitchat, or take a memorable photo.

Rather than presenting Picasso as a distant or heroic figure, the sculpture shows him seated casually on a bench, notebook and pencil in hand, dressed simply and appearing relaxed. The statue’s approachable scale and informal pose encourage interaction. The bench extends beyond the figure, leaving enough space for visitors to sit beside him.

Since its installation, the sculpture has become an active participant in the life of Merced Square. It regularly features in public performances and cultural events held in the square, including the annual White Night, celebrated since 2009, during which the statue is often decorated to match the event’s theme.

In April 2013, the statue became the centre of an unusual episode when a group of vandals attempted to steal it. The attempt failed due to the sculpture’s weight, and it was abandoned on a nearby bench.

Today, the statue has returned to its usual spot. You are free to sit beside Picasso, have a chitchat, or take a memorable photo.

3) Iglesia de Santiago Apóstol (Church of Santiago Apostol)

The Church of Santiago Apóstol is one of Málaga’s oldest Christian churches and a key landmark in the historic centre. Founded shortly after the conquest of Málaga in 1487, traditionally under the patronage of the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, it was built on the site of a former mosque and dedicated to Saint James the Apostle, a central symbol of the Reconquest.

Architecturally, the church reflects multiple historical layers. Its square brick tower was originally constructed as a minaret and later incorporated into the church in the 16th century. The tower still displays Almohad sebka decorative motifs, a clear reminder of its Islamic origins. Over time, the original Gothic and Mudéjar foundations were enriched with Renaissance and Baroque additions.

Inside, the church opens into three naves, adorned with significant works by Baroque painters such as Alonso Cano and Niño de Guevara. Among its treasures is a finely crafted 16th-century Plateresque chalice, distinguished by its star-shaped foot and hexagonal body. At the front of the central nave stands a monumental 18th-century Baroque gilded altarpiece. Look for the central figure of Saint James, the church’s patron saint, depicted holding a scroll and a staff.

The church also plays an important role in Málaga’s Holy Week traditions. As you face the altar, the left nave, known as the Gospel Nave, houses two venerated processional images: the Virgin of Love and Jesus the Rich, associated with the annual Holy Week tradition of releasing a prisoner. These mannequin-like figures are located in the second niche of the left nave. Another focal point of devotion is the Christ of Medinaceli, a 17th-century image honoured each year on the first Friday of March. On that day, the figure is removed from its niche, redressed, and placed on a gilded platform. Devotees kiss his feet, leave three coins, and make three wishes—of which, tradition says, only one will be granted. The Christ of Medinaceli is found in the second niche of the right nave, directly opposite the figures in the left nave.

The Church of Santiago is also closely linked to Pablo Picasso, who was baptised here on November 10, 1881. The church’s façade on Granada Street features three wide doors. The door farthest from the tower is accompanied, to its right, by a commemorative stone plaque marking the baptism. Picasso’s baptismal certificate is preserved inside, directly connecting the church to one of Málaga’s most famous sons.

Architecturally, the church reflects multiple historical layers. Its square brick tower was originally constructed as a minaret and later incorporated into the church in the 16th century. The tower still displays Almohad sebka decorative motifs, a clear reminder of its Islamic origins. Over time, the original Gothic and Mudéjar foundations were enriched with Renaissance and Baroque additions.

Inside, the church opens into three naves, adorned with significant works by Baroque painters such as Alonso Cano and Niño de Guevara. Among its treasures is a finely crafted 16th-century Plateresque chalice, distinguished by its star-shaped foot and hexagonal body. At the front of the central nave stands a monumental 18th-century Baroque gilded altarpiece. Look for the central figure of Saint James, the church’s patron saint, depicted holding a scroll and a staff.

The church also plays an important role in Málaga’s Holy Week traditions. As you face the altar, the left nave, known as the Gospel Nave, houses two venerated processional images: the Virgin of Love and Jesus the Rich, associated with the annual Holy Week tradition of releasing a prisoner. These mannequin-like figures are located in the second niche of the left nave. Another focal point of devotion is the Christ of Medinaceli, a 17th-century image honoured each year on the first Friday of March. On that day, the figure is removed from its niche, redressed, and placed on a gilded platform. Devotees kiss his feet, leave three coins, and make three wishes—of which, tradition says, only one will be granted. The Christ of Medinaceli is found in the second niche of the right nave, directly opposite the figures in the left nave.

The Church of Santiago is also closely linked to Pablo Picasso, who was baptised here on November 10, 1881. The church’s façade on Granada Street features three wide doors. The door farthest from the tower is accompanied, to its right, by a commemorative stone plaque marking the baptism. Picasso’s baptismal certificate is preserved inside, directly connecting the church to one of Málaga’s most famous sons.

4) Museo Picasso Málaga (Picasso Museum) (must see)

The Picasso Museum is rooted directly in the city where Pablo Picasso was born in 1881 and occupies the Buenavista Palace, a 16th-century aristocratic residence in Málaga’s historic centre.

Picasso’s father, José Ruiz, served as curator of Málaga’s city museum, which operated under tight budgets and was rarely open to the public. As part of his compensation, Ruiz was granted exclusive use of a room as an art studio, where the young Pablo made his earliest sketches under his father’s guidance. Although Picasso would later be represented by major museums in Paris and Barcelona, the Málaga museum holds particular significance: it stands only a short walk from Merced Square, where he was born.

The idea of establishing a Picasso museum in Málaga circulated for decades before becoming a reality in the early 21st century, driven by the artist’s family. The museum opened in 2003, following a substantial donation of works from Christine and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, with the official inauguration attended by the King and Queen of Spain.

Rather than concentrating on a single period, the collection traces Picasso’s artistic evolution across his entire career. Typically organised chronologically across 11 galleries, it begins with Picasso’s early academic works, led by the 1895 painting Portrait of a Bearded Man. The rooms dedicated to his Neoclassical period contain one of the museum’s crown jewels—the 1923 painting The Three Graces. Toward the end of the circuit, visitors encounter Picasso’s works from the 1970s, which are noticeably more colourful and expressive. Temporary exhibitions regularly place the artist’s work in dialogue with other creators and themes.

Beneath the palace lie archaeological remains, including partially preserved structures from a Nasrid palace alongside earlier Roman traces. Visitors can walk on glass walkways over 2,500-year-old city walls and the remains of a Roman fish-salting factory. One of the main highlights of the basement level is the Phoenician wall dating from the 7th and 8th centuries BC. The archaeological site is accessible via staircases or an elevator.

The institution also houses an archive of documents and photographs, as well as a specialised library containing more than 14,000 titles devoted to Picasso.

Picasso’s father, José Ruiz, served as curator of Málaga’s city museum, which operated under tight budgets and was rarely open to the public. As part of his compensation, Ruiz was granted exclusive use of a room as an art studio, where the young Pablo made his earliest sketches under his father’s guidance. Although Picasso would later be represented by major museums in Paris and Barcelona, the Málaga museum holds particular significance: it stands only a short walk from Merced Square, where he was born.

The idea of establishing a Picasso museum in Málaga circulated for decades before becoming a reality in the early 21st century, driven by the artist’s family. The museum opened in 2003, following a substantial donation of works from Christine and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, with the official inauguration attended by the King and Queen of Spain.

Rather than concentrating on a single period, the collection traces Picasso’s artistic evolution across his entire career. Typically organised chronologically across 11 galleries, it begins with Picasso’s early academic works, led by the 1895 painting Portrait of a Bearded Man. The rooms dedicated to his Neoclassical period contain one of the museum’s crown jewels—the 1923 painting The Three Graces. Toward the end of the circuit, visitors encounter Picasso’s works from the 1970s, which are noticeably more colourful and expressive. Temporary exhibitions regularly place the artist’s work in dialogue with other creators and themes.

Beneath the palace lie archaeological remains, including partially preserved structures from a Nasrid palace alongside earlier Roman traces. Visitors can walk on glass walkways over 2,500-year-old city walls and the remains of a Roman fish-salting factory. One of the main highlights of the basement level is the Phoenician wall dating from the 7th and 8th centuries BC. The archaeological site is accessible via staircases or an elevator.

The institution also houses an archive of documents and photographs, as well as a specialised library containing more than 14,000 titles devoted to Picasso.

5) Convento de San Agustín de Málaga (San Agustín Convent)

The San Agustín Convent is one of Málaga’s lesser-known yet historically significant religious complexes, closely tied to the city’s post-Reconquest development. Located on San Agustín Street, the convent was built on land purchased by the Augustinian friars in 1575. Its foundation formed part of Málaga’s late-16th-century urban expansion, as new Christian institutions took shape within the former Islamic city.

Over time, the convent grew into a substantial complex that included a church, cloister, and monastic buildings. Its architecture evolved gradually, combining restrained Renaissance forms with later Baroque additions, particularly in interior decoration.

The 19th century brought repeated disruptions. The convent was damaged during the French invasion in 1810 and did not resume activity until 1812, at the height of the Napoleonic wars. In the decades that followed, the building passed through a series of civic roles, serving successively as city hall, a blood hospital, and a seminary. In 1913, after this period of constant reassignment, it became an Augustinian school.

The site was familiar to the Picasso family. While the building functioned as city hall, Picasso’s father, José Ruiz Blasco, worked as a curator for painting exhibitions held there. Later, the school allowed him to use a workshop as an art studio where he taught. A fellow teacher recalled the space as modest: “a little dirtier than the one I had at home; but it was quiet.” This understated setting forms part of the everyday landscape in which Picasso’s early artistic life unfolded.

Over time, the convent grew into a substantial complex that included a church, cloister, and monastic buildings. Its architecture evolved gradually, combining restrained Renaissance forms with later Baroque additions, particularly in interior decoration.

The 19th century brought repeated disruptions. The convent was damaged during the French invasion in 1810 and did not resume activity until 1812, at the height of the Napoleonic wars. In the decades that followed, the building passed through a series of civic roles, serving successively as city hall, a blood hospital, and a seminary. In 1913, after this period of constant reassignment, it became an Augustinian school.

The site was familiar to the Picasso family. While the building functioned as city hall, Picasso’s father, José Ruiz Blasco, worked as a curator for painting exhibitions held there. Later, the school allowed him to use a workshop as an art studio where he taught. A fellow teacher recalled the space as modest: “a little dirtier than the one I had at home; but it was quiet.” This understated setting forms part of the everyday landscape in which Picasso’s early artistic life unfolded.

6) Centro Cultural La Malagueta (La Malagueta Cultural Center)

La Malagueta Cultural Center is one of Málaga’s most recognisable landmarks and a key example of late-19th-century civic architecture. It was inaugurated in 1876, at a time when the city was expanding beyond its historic core. For most of its history, La Malagueta’s primary function was hosting bullfights. However, in January 2020, the building entered a new phase, when its former stables and storage rooms were transformed into climate-controlled indoor spaces, allowing for a wider range of exhibitions and conferences. This transformation also marked the official change of name from “La Malagueta Bullring” to “La Malagueta Cultural Center.”

Designed by architect Joaquín Rucoba, the structure reflects the Neo-Mudéjar style then in vogue, combining brick construction with horseshoe arches and restrained decorative details that give the exterior a strong rhythmic character.

The building is organised around a large, almost circular arena enclosed by tiered seating and a continuous arcade. Conceived as a permanent civic venue, it quickly became an established stage for public events. During the bullfighting season, La Malagueta still hosts major corridas, including two events during Holy Week. One of these, the Corrida Picassiana, pays tribute to Pablo Picasso, who developed a lifelong fascination with bullfighting after attending events here as a child, often accompanied by his father.

This early exposure left a lasting mark on Picasso’s work. The contest between man and bull appears repeatedly in his sketches and paintings. In a 1925 portrait of his son Paul, the child is shown dressed as a bullfighter, red cape in hand, with the subtle outline of a bullring visible in the background.

Today, La Malagueta also houses the Antonio Ordóñez Bullfighting Museum, whose entrance is located at Gate 8 on the southeast façade of the arena. The museum’s highlights include a collection of “suits of lights,” historical posters, and bullfighting artefacts. Among them, the suit worn by Málaga-born bullfighter Javier Conde—designed by French fashion designer Christian Lacroix— stands out as the most striking. Visitors pass through Rooms A, B, and C before reaching Room D, where Conde’s suit forms the central display.

Beyond corridas, the arena is also used for concerts and other cultural events.

Designed by architect Joaquín Rucoba, the structure reflects the Neo-Mudéjar style then in vogue, combining brick construction with horseshoe arches and restrained decorative details that give the exterior a strong rhythmic character.

The building is organised around a large, almost circular arena enclosed by tiered seating and a continuous arcade. Conceived as a permanent civic venue, it quickly became an established stage for public events. During the bullfighting season, La Malagueta still hosts major corridas, including two events during Holy Week. One of these, the Corrida Picassiana, pays tribute to Pablo Picasso, who developed a lifelong fascination with bullfighting after attending events here as a child, often accompanied by his father.

This early exposure left a lasting mark on Picasso’s work. The contest between man and bull appears repeatedly in his sketches and paintings. In a 1925 portrait of his son Paul, the child is shown dressed as a bullfighter, red cape in hand, with the subtle outline of a bullring visible in the background.

Today, La Malagueta also houses the Antonio Ordóñez Bullfighting Museum, whose entrance is located at Gate 8 on the southeast façade of the arena. The museum’s highlights include a collection of “suits of lights,” historical posters, and bullfighting artefacts. Among them, the suit worn by Málaga-born bullfighter Javier Conde—designed by French fashion designer Christian Lacroix— stands out as the most striking. Visitors pass through Rooms A, B, and C before reaching Room D, where Conde’s suit forms the central display.

Beyond corridas, the arena is also used for concerts and other cultural events.

Walking Tours in Malaga, Spain

Create Your Own Walk in Malaga

Creating your own self-guided walk in Malaga is easy and fun. Choose the city attractions that you want to see and a walk route map will be created just for you. You can even set your hotel as the start point of the walk.

Malaga Introduction Walking Tour

In 1325, the famed Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta reflected on his visit to Málaga, writing: "It is one of the largest and most beautiful towns of Andalusia, combining the conveniences of both sea and land.''

Málaga is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Europe, with a history spanning nearly three millennia. It was founded around the 8th century BC by Phoenician... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.4 Km or 2.1 Miles

Málaga is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Europe, with a history spanning nearly three millennia. It was founded around the 8th century BC by Phoenician... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.4 Km or 2.1 Miles

Architectural Jewels of Malaga

The blooming port city of Málaga has a wealth of architecture with no shortage of ancient and otherwise impressive buildings fit to vow any visitor. Having witnessed the fall and rise of many civilizations, Malaga's uniqueness is marked by the variety of architectural styles, upon which the times past had a great deal of impact. From its stunning Moorish fortress – the best-preserved of... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Useful Travel Guides for Planning Your Trip

5 Best Shopping Streets in Malaga, Spain

As well as one of the best cultural destinations in southern Spain, Malaga turns out to be something of a shopping mecca. Along with the ubiquitous shopping malls on the outskirts, the capital of Costa del Sol has managed to preserve its network of specialist shops, difficult to find in most big...

The Most Popular Cities

/ view all