Muslim Quarter & Temple Mount Tour (Self Guided), Jerusalem

The largest, most populous and perhaps most chaotic of all Jerusalem’s quarters, the Muslim Quarter is worth exploring for its unique atmosphere. Spending a day here may take you back to a simpler time, but be prepared for many sights and sounds as you pass many vendors, stores and restaurants on your way from site to site.

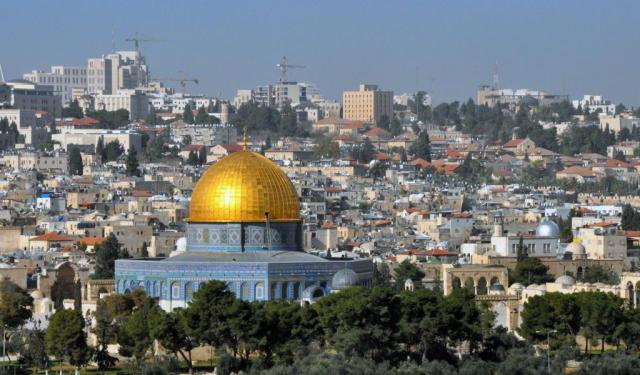

Some of the city’s most interesting city gates (Damascus and Lion’s) are located in the area. Importantly, the Muslim Quarter is also the location of the Temple Mount, sacred to three great monotheistic religions, and the Dome of the Rock, probably the most easily recognizable landmark due to its enormous golden dome. Situated on the edge of the Old City, this extraordinary shrine was built over the rock where tradition says Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven and Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son.

Christian visitors to Jerusalem will want to invest additional time visiting historic church sights like St. Anne’s (the birthplace of the Virgin Mary, according to Catholic tradition) and the Church of the Flagellation, held to be where Jesus took up his cross after being sentenced to death by crucifixion.

For a vibrant shopping experience, just inside of Damascus Gate is the gateway to the Arab Souk, where you can find trinkets, clothes, jewelry, plus many spices, sweets, raw meat, and other food.

Comprising these and more, our self-guided walking tour will help navigate your way through some of the Muslim Quarter’s most alluring attractions – so wear comfortable shoes and explore at your own pace.

Some of the city’s most interesting city gates (Damascus and Lion’s) are located in the area. Importantly, the Muslim Quarter is also the location of the Temple Mount, sacred to three great monotheistic religions, and the Dome of the Rock, probably the most easily recognizable landmark due to its enormous golden dome. Situated on the edge of the Old City, this extraordinary shrine was built over the rock where tradition says Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven and Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son.

Christian visitors to Jerusalem will want to invest additional time visiting historic church sights like St. Anne’s (the birthplace of the Virgin Mary, according to Catholic tradition) and the Church of the Flagellation, held to be where Jesus took up his cross after being sentenced to death by crucifixion.

For a vibrant shopping experience, just inside of Damascus Gate is the gateway to the Arab Souk, where you can find trinkets, clothes, jewelry, plus many spices, sweets, raw meat, and other food.

Comprising these and more, our self-guided walking tour will help navigate your way through some of the Muslim Quarter’s most alluring attractions – so wear comfortable shoes and explore at your own pace.

How it works: Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" from Apple App Store or Google Play Store to your mobile phone or tablet. The app turns your mobile device into a personal tour guide and its built-in GPS navigation functions guide you from one tour stop to next. The app works offline, so no data plan is needed when traveling abroad.

Muslim Quarter & Temple Mount Tour Map

Guide Name: Muslim Quarter & Temple Mount Tour

Guide Location: Israel » Jerusalem (See other walking tours in Jerusalem)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 12

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.1 Km or 1.3 Miles

Author: vickyc

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

Guide Location: Israel » Jerusalem (See other walking tours in Jerusalem)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 12

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.1 Km or 1.3 Miles

Author: vickyc

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

- Lions' Gate

- Pools of Bethesda

- Churches of St. Anne

- Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra)

- Dome of the Chain (Qubbat al-Silsilah)

- Al-Aqsa Mosque (Masjid al-Aqsa)

- Islamic Museum of Temple Mount

- Dome of the Ascension (Qubbat al-Miraj)

- Cotton Merchants' Gate and Market (Souk el-Qattanin)

- Convent of the Flagellation

- Ecce Homo Arch

- Beit Habad Street Market (Souk Khan El-Zeit)

1) Lions' Gate

This entrance in Jerusalem’s eastern wall answers to several names, which already tells you it has lived a busy life. Most visitors know it as the Lions’ Gate, thanks to the pair of stone beasts guarding the doorway. Christians, meanwhile, often call it Saint Stephen’s Gate, after the first Christian martyr, who was stoned outside the city. His burial place originally lay near Damascus Gate, but was later shifted here, making life a little easier for generations of pilgrims.

Arabic names add more layers to the story. One is Bab al-Ghor, or “Jordan Valley Gate,” pointing east toward the land below. Another links the gate to the Virgin Mary, believed by tradition to have been born nearby. Then there’s Meshikuli, a term best translated as “wicket”—a reminder that gates were once part of a defensive system, not a photo opportunity. Through openings like this, watchful eyes scanned the horizon, ready to respond to anything approaching, sometimes with less-than-hospitable methods, involving boiling oil.

The animals themselves come with their own debate. Officially, they’re lions, though some insist they’re panthers. One tradition connects them to the Mamluk sultan Baybars I, whose emblem they resemble. According to legend, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent ordered them placed here to celebrate driving the Crusaders from the region. Another story claims the decision followed a dream in which Suleiman was threatened by lions if he failed to rebuild Jerusalem’s walls—a reminder that urban planning has always had its anxieties...

What’s remarkable is how little the gate has changed. Unlike much of the Old City, it has never been restored. It still does its job quietly, funneling crowds in and out—especially on Fridays, when worshipers stream toward the nearby Al-Aqsa Mosque. Stand here for a moment, and you’ll see exactly what this gate has always done best: connect names, beliefs, and centuries of history in one narrow opening.

Arabic names add more layers to the story. One is Bab al-Ghor, or “Jordan Valley Gate,” pointing east toward the land below. Another links the gate to the Virgin Mary, believed by tradition to have been born nearby. Then there’s Meshikuli, a term best translated as “wicket”—a reminder that gates were once part of a defensive system, not a photo opportunity. Through openings like this, watchful eyes scanned the horizon, ready to respond to anything approaching, sometimes with less-than-hospitable methods, involving boiling oil.

The animals themselves come with their own debate. Officially, they’re lions, though some insist they’re panthers. One tradition connects them to the Mamluk sultan Baybars I, whose emblem they resemble. According to legend, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent ordered them placed here to celebrate driving the Crusaders from the region. Another story claims the decision followed a dream in which Suleiman was threatened by lions if he failed to rebuild Jerusalem’s walls—a reminder that urban planning has always had its anxieties...

What’s remarkable is how little the gate has changed. Unlike much of the Old City, it has never been restored. It still does its job quietly, funneling crowds in and out—especially on Fridays, when worshipers stream toward the nearby Al-Aqsa Mosque. Stand here for a moment, and you’ll see exactly what this gate has always done best: connect names, beliefs, and centuries of history in one narrow opening.

2) Pools of Bethesda

Just beside the serene Saint Anne’s Church, history takes a sharp turn underground. Here lie the Pools of Bethesda, built around 200 BC to supply water to the Temple—practical infrastructure with a spiritual reputation. According to the Gospel of Saint John, these waters were believed to heal, and it’s here that Jesus is said to have cured a man who had been ill for 38 years. Not bad credentials for a water system...

Archaeology fills in the background details. Excavations uncovered the remains of five porticoes, matching the biblical description, along with nearby caves that the Romans converted into bathing areas. In Roman times, this was less a quiet sanctuary and more a full-scale healing complex, crowded with people hoping the waters might change their fortunes. The Romans later added their own layer, constructing a 3rd-century temple dedicated to Serapis (the god of the underworld, healing, fertility, and the heavens), which was eventually replaced by a Byzantine basilica—because in Jerusalem, even sacred real estate gets reused.

Today, a raised walkway lets you circle the pools and peer down into centuries of engineering, ritual, and belief. You can descend into a Roman cistern, trace the outlines of walls and arches, and see how one site absorbed pagan worship, Christian tradition, and urban infrastructure without ever fully pressing reset. A detailed plan helps keep the centuries straight.

There’s also a small on-site museum displaying finds from the excavations—quiet, modest, and usually open only by appointment. But even without it, the Pools of Bethesda tell their story clearly enough: a place where water, faith, and history have been flowing together for more than two thousand years.

Archaeology fills in the background details. Excavations uncovered the remains of five porticoes, matching the biblical description, along with nearby caves that the Romans converted into bathing areas. In Roman times, this was less a quiet sanctuary and more a full-scale healing complex, crowded with people hoping the waters might change their fortunes. The Romans later added their own layer, constructing a 3rd-century temple dedicated to Serapis (the god of the underworld, healing, fertility, and the heavens), which was eventually replaced by a Byzantine basilica—because in Jerusalem, even sacred real estate gets reused.

Today, a raised walkway lets you circle the pools and peer down into centuries of engineering, ritual, and belief. You can descend into a Roman cistern, trace the outlines of walls and arches, and see how one site absorbed pagan worship, Christian tradition, and urban infrastructure without ever fully pressing reset. A detailed plan helps keep the centuries straight.

There’s also a small on-site museum displaying finds from the excavations—quiet, modest, and usually open only by appointment. But even without it, the Pools of Bethesda tell their story clearly enough: a place where water, faith, and history have been flowing together for more than two thousand years.

3) Churches of St. Anne (must see)

Just inside Lions' Gate, tucked within a quiet walled compound, you’ll find not one but two Churches of Saint Anne—both dedicated to Anne, traditionally known as the mother of the Virgin Mary. Closest to the gate stands the Greek Orthodox church. It is modest in scale and gently atmospheric, with a small cave-like chapel that tradition associates with Mary’s birth. Below, a stairway leads to the tombs attributed to her parents, Saints Anne and Joachim. The doors open at set hours, and a small donation is the customary way of saying thanks.

Right next door is the 12th-century Greek Catholic church, a Crusader-era building that proves simplicity can be quietly impressive. Its architecture mixes Romanesque clarity with Middle Eastern details—pointed arches and a fluted window frame that would later travel west with the Crusaders. Inside, the space is spare and luminous, with smooth columns and clean vaults that draw the eye upward. Then there’s the sound: the acoustics are so precise that the pilgrim groups often come here to sing rather than to look, letting hymns linger in the air long after the final note.

A set of steps descends to an older crypt, where Byzantine columns and mosaic fragments hint at even earlier layers of worship. Catholic tradition places Mary’s birth here, though today the site is presented with thoughtful restraint rather than firm claims—history speaking softly instead of shouting...

Before you move on, pause for two small pleasures. First, notice the building’s asymmetry—count the steps on either side, and you’ll see it. Second, step into the adjoining garden, a calm pocket of green that feels almost unreal this close to the Old City’s busiest paths. It’s a gentle reminder that in Jerusalem, even the quiet corners carry centuries of stories—and sometimes, they whisper them.

Right next door is the 12th-century Greek Catholic church, a Crusader-era building that proves simplicity can be quietly impressive. Its architecture mixes Romanesque clarity with Middle Eastern details—pointed arches and a fluted window frame that would later travel west with the Crusaders. Inside, the space is spare and luminous, with smooth columns and clean vaults that draw the eye upward. Then there’s the sound: the acoustics are so precise that the pilgrim groups often come here to sing rather than to look, letting hymns linger in the air long after the final note.

A set of steps descends to an older crypt, where Byzantine columns and mosaic fragments hint at even earlier layers of worship. Catholic tradition places Mary’s birth here, though today the site is presented with thoughtful restraint rather than firm claims—history speaking softly instead of shouting...

Before you move on, pause for two small pleasures. First, notice the building’s asymmetry—count the steps on either side, and you’ll see it. Second, step into the adjoining garden, a calm pocket of green that feels almost unreal this close to the Old City’s busiest paths. It’s a gentle reminder that in Jerusalem, even the quiet corners carry centuries of stories—and sometimes, they whisper them.

4) Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra)

The Dome of the Rock doesn’t ease into the conversation—it announces itself. That golden dome, the deep blues, the almost unnerving balance of proportions all signal that this is architecture designed to be seen, remembered, and quietly debated. Commissioned in the late 7th century AD by Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, the building made a clear statement: Islam belonged at the very center of Jerusalem’s sacred landscape, standing visually and symbolically alongside monuments like the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Despite what many assume, this is not a mosque. There’s no formal prayer hall, no qibla wall directing worshipers toward Mecca. Instead, the structure is a shrine, built to frame and protect a single object of immense significance: the exposed rock at its center. According to tradition, this is the place where Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son, and it also rises from what remained of Herod the Great’s Second Temple platform. Abd al-Malik chose not to build over that history, but around it, letting the rock remain both visible and central.

At a closer look, the surface becomes a lesson in precision and restraint. Marble panels line the lower walls, while bands of glazed blue and green tiles carry Quranic inscriptions, interlaced with geometric and floral designs. Much of the exterior decoration dates to the 16th century, when Suleiman the Magnificent ordered a major renovation that fixed the Dome’s visual identity for centuries to come.

The dome itself has had a practical life as well as a symbolic one. In the 1960s, its original lead covering—heavy and problematic—was replaced with anodized aluminum, later finished in gold. It’s a reminder that even icons need maintenance. Yet through repairs, restorations, and reinterpretations, the Dome of the Rock has never lost its role: not just as a landmark of Jerusalem, but as a carefully calculated statement of faith, history, and permanence—still holding the skyline, and the conversation, in perfect balance.

Despite what many assume, this is not a mosque. There’s no formal prayer hall, no qibla wall directing worshipers toward Mecca. Instead, the structure is a shrine, built to frame and protect a single object of immense significance: the exposed rock at its center. According to tradition, this is the place where Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son, and it also rises from what remained of Herod the Great’s Second Temple platform. Abd al-Malik chose not to build over that history, but around it, letting the rock remain both visible and central.

At a closer look, the surface becomes a lesson in precision and restraint. Marble panels line the lower walls, while bands of glazed blue and green tiles carry Quranic inscriptions, interlaced with geometric and floral designs. Much of the exterior decoration dates to the 16th century, when Suleiman the Magnificent ordered a major renovation that fixed the Dome’s visual identity for centuries to come.

The dome itself has had a practical life as well as a symbolic one. In the 1960s, its original lead covering—heavy and problematic—was replaced with anodized aluminum, later finished in gold. It’s a reminder that even icons need maintenance. Yet through repairs, restorations, and reinterpretations, the Dome of the Rock has never lost its role: not just as a landmark of Jerusalem, but as a carefully calculated statement of faith, history, and permanence—still holding the skyline, and the conversation, in perfect balance.

5) Dome of the Chain (Qubbat al-Silsilah)

Adjacently east of Dome of the Rock, at the heart of the Temple Mount complex, the 7th-century Dome of the Chain is perhaps the most impressive smaller domes within the Haram. While its original purpose remains shrouded in mystery, it has been speculated to have served as a model for the Dome of the Rock or as the Treasury of the Temple Mount.

Legend has it that during the time of King Solomon, a chain hung from the dome's roof. If two individuals approached seeking resolution to a dispute, only the truthful and righteous one could grasp the chain; the dishonest would find it beyond their reach. Alternatively, those who dared to tell falsehoods while holding the chain risked being struck down by lightning. In Islamic tradition, this site is believed to be where Judgment Day will unfold during the "end of days", with a chain separating the righteous from the sinful.

Adorned with delicate blue and white tilework dating back to the Ottoman era (16th century), the interior of the dome exudes a sense of serenity. The mihrab, or prayer niche, found within the dome's single wall, reflects the distinctive Mamluk style, with lots of intricate stripey ablaq patterns, including the triple-colored arch which surmounts it, evoking almost flame-like motifs that captivate the eye.

Legend has it that during the time of King Solomon, a chain hung from the dome's roof. If two individuals approached seeking resolution to a dispute, only the truthful and righteous one could grasp the chain; the dishonest would find it beyond their reach. Alternatively, those who dared to tell falsehoods while holding the chain risked being struck down by lightning. In Islamic tradition, this site is believed to be where Judgment Day will unfold during the "end of days", with a chain separating the righteous from the sinful.

Adorned with delicate blue and white tilework dating back to the Ottoman era (16th century), the interior of the dome exudes a sense of serenity. The mihrab, or prayer niche, found within the dome's single wall, reflects the distinctive Mamluk style, with lots of intricate stripey ablaq patterns, including the triple-colored arch which surmounts it, evoking almost flame-like motifs that captivate the eye.

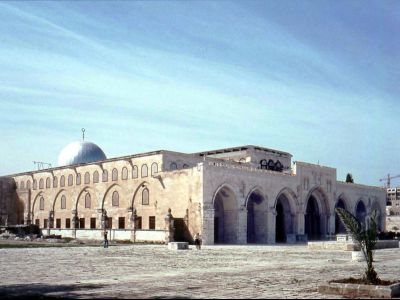

6) Al-Aqsa Mosque (Masjid al-Aqsa)

Masjid al-Aqsa—literally “the Farthest Mosque”—doesn’t try to outshine its flashier neighbor, the Dome of the Rock. It’s more restrained, more grounded, and very much aware of its own long memory. Standing on the Temple Mount, it marks the site traditionally linked to the first mosque built in Jerusalem in 638, connected to the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey, which placed this spot firmly into Islamic sacred geography.

History, however, has rarely left Al-Aqsa alone. Earthquakes, fires, and political upheavals have damaged it repeatedly, turning rebuilding into a recurring theme rather than a one-off event.

During the Crusader period, subtlety went out the window. The mosque was converted into a church, a cross was planted on its dome, and the underground vaults were repurposed as stables for Crusader horses—hence the enduring nickname, “Solomon’s Stables.” The Knights Templar order, founded in 1118, even borrowed their name from this complex, which the Crusaders confidently labeled the Templum, as if the past could be neatly reassigned.

That phase didn’t last, though. When Saladin retook Jerusalem, the Christian alterations were removed, and Al-Aqsa was restored as a mosque. The interior was carefully renewed, including the installation of an elaborate cedarwood minbar (pulpit) brought from Damascus, richly inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl. Although that pulpit was lost in a devastating fire in 1969, much of the mosque’s character survived—its mosaics, rose window, and original columns still quietly holding their ground.

What you see today is largely the result of 20th-century restoration, but don’t mistake “modern” for “plain.” Inside are seven aisles, marble columns, and 121 stained-glass windows that soften the light and slow the pace. Entry for non-Muslims is restricted, yet even from the outside, Al-Aqsa speaks volumes. It’s a building that doesn’t shout its importance—it lets history do the talking.

History, however, has rarely left Al-Aqsa alone. Earthquakes, fires, and political upheavals have damaged it repeatedly, turning rebuilding into a recurring theme rather than a one-off event.

During the Crusader period, subtlety went out the window. The mosque was converted into a church, a cross was planted on its dome, and the underground vaults were repurposed as stables for Crusader horses—hence the enduring nickname, “Solomon’s Stables.” The Knights Templar order, founded in 1118, even borrowed their name from this complex, which the Crusaders confidently labeled the Templum, as if the past could be neatly reassigned.

That phase didn’t last, though. When Saladin retook Jerusalem, the Christian alterations were removed, and Al-Aqsa was restored as a mosque. The interior was carefully renewed, including the installation of an elaborate cedarwood minbar (pulpit) brought from Damascus, richly inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl. Although that pulpit was lost in a devastating fire in 1969, much of the mosque’s character survived—its mosaics, rose window, and original columns still quietly holding their ground.

What you see today is largely the result of 20th-century restoration, but don’t mistake “modern” for “plain.” Inside are seven aisles, marble columns, and 121 stained-glass windows that soften the light and slow the pace. Entry for non-Muslims is restricted, yet even from the outside, Al-Aqsa speaks volumes. It’s a building that doesn’t shout its importance—it lets history do the talking.

7) Islamic Museum of Temple Mount

Sited on the Temple Mount toward its Moroccan gate (or to the right of Al-Aqsa Mosque, this quaint museum stands as one of the country's oldest, holding a remarkable collection of rare artifacts spanning ten periods of Islamic history. From 16th-century copper soup kettles to coins, stained glass windows, and iron doors hailing from the era of Suleiman the Magnificent, the exhibits offer a fascinating glimpse into the rich heritage of the region.

Among the highlights are a cannon used to announce the end of Ramadan, a diverse array of weapons, along with unique items like a wax tree trunk and the charred remnants of a minbar crafted by Nur ad-Din Zangi in the 1170s, tragically destroyed in a 1969 incident involving an Australian tourist. Additionally, poignant relics such as the blood-stained clothing of 17 Palestinians who lost their lives during the 1990 Temple Mount riots serve as sobering reminders of the site's tumultuous history.

Also of note are the museum's 600 copies of the Qur'an, generously donated to the Al-Aqsa Mosque over the centuries by caliphs, sultans, scholars, and private individuals. Each copy is a unique treasure, varying in size, calligraphy, and ornamentation. One such copy is a handwritten Qur'ans attributed to the great-great-grandson of Muhammad, while another is written in ancient Kufic script dating back to the 8th-9th century. In addition, there is a massive Qur'an measuring 100 by 90 centimeters, dating to the 14th century.

Tip:

The admission fee also allow entry to the Al-Aqsa Mosque, contingent upon the prevailing security conditions at the time of visitation

Among the highlights are a cannon used to announce the end of Ramadan, a diverse array of weapons, along with unique items like a wax tree trunk and the charred remnants of a minbar crafted by Nur ad-Din Zangi in the 1170s, tragically destroyed in a 1969 incident involving an Australian tourist. Additionally, poignant relics such as the blood-stained clothing of 17 Palestinians who lost their lives during the 1990 Temple Mount riots serve as sobering reminders of the site's tumultuous history.

Also of note are the museum's 600 copies of the Qur'an, generously donated to the Al-Aqsa Mosque over the centuries by caliphs, sultans, scholars, and private individuals. Each copy is a unique treasure, varying in size, calligraphy, and ornamentation. One such copy is a handwritten Qur'ans attributed to the great-great-grandson of Muhammad, while another is written in ancient Kufic script dating back to the 8th-9th century. In addition, there is a massive Qur'an measuring 100 by 90 centimeters, dating to the 14th century.

Tip:

The admission fee also allow entry to the Al-Aqsa Mosque, contingent upon the prevailing security conditions at the time of visitation

8) Dome of the Ascension (Qubbat al-Miraj)

Aside from the iconic Dome of the Rock, the Temple Mount complex houses an array of nine other domes, each with its own unique significance. Among them stands the elegantly simple Dome of the Ascension, distinguished by its octagonal shape. While its original construction date by the Crusaders remains shrouded in mystery, records indicate a restoration in 1200 AD.

Legend has it that this humble dome marks the very spot where Jesus bid farewell to his disciples before ascending to heaven, with a small piece of bedrock purportedly bearing the imprint of his foot. While Arabic tradition refers to it as the "Dome of the Ascension" in honor of the Prophet Muhammad's legendary ascent to the Divine Throne from this site, scholars suggest that it was initially built as part of the Christian Templum Domini, likely serving as a baptistry.

An Arabic inscription dating back to 1200-1 offers further insight, describing its rededication as a waqf, or religious endowment, underscoring its evolving religious significance over the centuries.

Legend has it that this humble dome marks the very spot where Jesus bid farewell to his disciples before ascending to heaven, with a small piece of bedrock purportedly bearing the imprint of his foot. While Arabic tradition refers to it as the "Dome of the Ascension" in honor of the Prophet Muhammad's legendary ascent to the Divine Throne from this site, scholars suggest that it was initially built as part of the Christian Templum Domini, likely serving as a baptistry.

An Arabic inscription dating back to 1200-1 offers further insight, describing its rededication as a waqf, or religious endowment, underscoring its evolving religious significance over the centuries.

9) Cotton Merchants' Gate and Market (Souk el-Qattanin)

Known as the Souk el-Qattanin in Arabic, this covered market exudes an enchanting ambiance with its softly lit shops, creating an atmosphere that's arguably unmatched anywhere else in the Old City. Originally initiated by the Crusaders as a freestanding structure, its evolution took a significant turn in the first half of the 14th century when the Mamelukes linked it to the Haram ash-Sharif via the magnificent Cotton Merchants' Gate, offering a splendid view facing the Dome of the Rock. (Please note, access to the Haram via this gate is restricted to Muslims only, though non-Muslims may exit through it.)

Comprising around 50 shop units with living quarters above, the market also houses two exquisite bathhouses: the Hammam el-Ain, built by the Mamelukes in the 14th century, and the Hammam el-Shifa. Recently restored, the former now serves as a spa while the latter has been repurposed as an art gallery. Between these bathhouses lies the Khan Tankiz, a former hostel for merchants and pilgrims, which has also undergone restoration. Though not officially open to the public, a peek inside may be possible upon request.

Tip:

Just a stone's throw away from the market, on El-Wad Road, lies a small 16th-century public drinking fountain, or "sabil", one of six erected during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. Keep an eye out for this historical gem as you explore the area.

Comprising around 50 shop units with living quarters above, the market also houses two exquisite bathhouses: the Hammam el-Ain, built by the Mamelukes in the 14th century, and the Hammam el-Shifa. Recently restored, the former now serves as a spa while the latter has been repurposed as an art gallery. Between these bathhouses lies the Khan Tankiz, a former hostel for merchants and pilgrims, which has also undergone restoration. Though not officially open to the public, a peek inside may be possible upon request.

Tip:

Just a stone's throw away from the market, on El-Wad Road, lies a small 16th-century public drinking fountain, or "sabil", one of six erected during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. Keep an eye out for this historical gem as you explore the area.

10) Convent of the Flagellation

Belonging to the Franciscans, this compound encompasses the Chapel of the Flagellation, a striking yet simple structure crafted in the 1920s by the renowned Italian architect Antonio Barluzzi, known for his work on the Dominus Flevit Chapel on the Mount of Olives. Situated on the traditional site where Christ was scourged by Roman soldiers before his crucifixion, it marks the second station of the Via Dolorosa, following the Church of Saint Anne. Adorned with stained glass windows and an exquisite mosaic ceiling, the interior ingeniously depicts a circular pattern of thorns, subtly evoking the agonizing ordeal endured by Christ.

Across the courtyard lies the Chapel of the Condemnation, also originating from the early 20th century. Crowned by five elegant white domes, it stands atop the remnants of a medieval chapel, believed to be the location where Christ faced trial before Pontius Pilate. Noteworthy is the Roman-era floor adjacent to the building's western wall, constructed from large, striated stones designed to prevent animals' hooves from slipping-a glimpse into ancient ingenuity.

Nestled within the adjacent monastery buildings is the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, a renowned institute dedicated to biblical, geographical, and archaeological studies. Complementing this scholarly endeavor is the Studium Museum, housing artifacts unearthed by the Franciscans during excavations across sites such as Capernaum, Nazareth, and Bethlehem. Highlights include Byzantine and Crusader relics, including fragments of frescoes from the Church of Gethsemane and a 12th-century crozier from the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, offering visitors a captivating journey through the rich tapestry of biblical history.

Across the courtyard lies the Chapel of the Condemnation, also originating from the early 20th century. Crowned by five elegant white domes, it stands atop the remnants of a medieval chapel, believed to be the location where Christ faced trial before Pontius Pilate. Noteworthy is the Roman-era floor adjacent to the building's western wall, constructed from large, striated stones designed to prevent animals' hooves from slipping-a glimpse into ancient ingenuity.

Nestled within the adjacent monastery buildings is the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, a renowned institute dedicated to biblical, geographical, and archaeological studies. Complementing this scholarly endeavor is the Studium Museum, housing artifacts unearthed by the Franciscans during excavations across sites such as Capernaum, Nazareth, and Bethlehem. Highlights include Byzantine and Crusader relics, including fragments of frescoes from the Church of Gethsemane and a 12th-century crozier from the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, offering visitors a captivating journey through the rich tapestry of biblical history.

11) Ecce Homo Arch

Stretching across the Via Dolorosa, this arch looks quietly theatrical—and it has earned the role. Its story begins in 70 AD, when the Romans threw it up as part of a military ramp aimed at the Antonia Fortress, where Jewish rebels were holding out. A few decades later, after crushing the Second Jewish War, the Romans rebuilt Jerusalem in 135 AD and gave the arch a victory makeover: one large central opening flanked by two smaller arches. The main bay still spans the street here, just west of the entrance to the Lithostratos, better known as the “Pavement of Justice.”

One of those side arches didn’t vanish—it simply changed address. Today, it survives indoors, folded neatly into the Convent of the Sisters of Zion, built in the 1860s. Beneath the convent lies the Struthion Pool, an ancient reservoir designed to catch rainwater from the surrounding rooftops. Christian tradition places a dramatic moment here: the stone pavement above the pool is said to be where Pontius Pilate presented Jesus to the crowd with the words “Ecce homo”—“Behold the man.” Archaeology, however, plays the spoiler. The pavement dates to the 2nd century AD, from the reign of Emperor Hadrian, making it a later Roman addition rather than a firsthand witness to the trial.

Looking closely at the stone within the railed section, you will spot etched markings—circles and lines that historians believe were scratched by bored Roman guards, possibly for games played while on duty. It’s a small, human detail amid the heavy symbolism.

Just nearby, beside the Third Station, a building belonging to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate bears a plaque identifying it as the Prison of Jesus and Barabbas. That label only appeared in 1911, and scholars are unconvinced. More likely, this was once a stable tied to the Antonia Fortress—less drama, more logistics. Indeed, in Jerusalem, even the stones argue back...

One of those side arches didn’t vanish—it simply changed address. Today, it survives indoors, folded neatly into the Convent of the Sisters of Zion, built in the 1860s. Beneath the convent lies the Struthion Pool, an ancient reservoir designed to catch rainwater from the surrounding rooftops. Christian tradition places a dramatic moment here: the stone pavement above the pool is said to be where Pontius Pilate presented Jesus to the crowd with the words “Ecce homo”—“Behold the man.” Archaeology, however, plays the spoiler. The pavement dates to the 2nd century AD, from the reign of Emperor Hadrian, making it a later Roman addition rather than a firsthand witness to the trial.

Looking closely at the stone within the railed section, you will spot etched markings—circles and lines that historians believe were scratched by bored Roman guards, possibly for games played while on duty. It’s a small, human detail amid the heavy symbolism.

Just nearby, beside the Third Station, a building belonging to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate bears a plaque identifying it as the Prison of Jesus and Barabbas. That label only appeared in 1911, and scholars are unconvinced. More likely, this was once a stable tied to the Antonia Fortress—less drama, more logistics. Indeed, in Jerusalem, even the stones argue back...

12) Beit Habad Street Market (Souk Khan El-Zeit)

Tucked just behind Damascus Gate, this colorful and fascinating market is a living testament to centuries of tradition, pulsating with culture along every cobbled lane. Stepping into its bustling labyrinth can feel like a step back in time, where familiar customs of the Western world may not always apply – but that's all part of the adventure.

At the more genuine and authentic Khan El-Zeit and El-Wad streets, vendors peddle spices, fruits, falafels, and other consumables for locals, alongside embroidered dresses, leather goods, and countless other handicrafts. As you venture further along Via Dolorosa, you'll encounter a mix of traditional souk shops and tourist-friendly stalls. Chain Street, an extension of David Street from the Christian Quarter, is lined with one shop after another selling souvenirs – the perfect spot to snag a unique memento if you're willing to hunt for it.

Prepare to flex your haggling skills as you peruse the stalls – it's all part of the souk experience, and you may just score some fantastic bargains. While it's busy at any time of day, evenings bring a trendy vibe to the souk, with eateries and pubs coming to life.

Tip:

Hit the market in the morning for the freshest baked goods, and if you're craving the best shawarma, head to the Muslim quarter of the souk – where they're known to be both delicious and budget-friendly.

At the more genuine and authentic Khan El-Zeit and El-Wad streets, vendors peddle spices, fruits, falafels, and other consumables for locals, alongside embroidered dresses, leather goods, and countless other handicrafts. As you venture further along Via Dolorosa, you'll encounter a mix of traditional souk shops and tourist-friendly stalls. Chain Street, an extension of David Street from the Christian Quarter, is lined with one shop after another selling souvenirs – the perfect spot to snag a unique memento if you're willing to hunt for it.

Prepare to flex your haggling skills as you peruse the stalls – it's all part of the souk experience, and you may just score some fantastic bargains. While it's busy at any time of day, evenings bring a trendy vibe to the souk, with eateries and pubs coming to life.

Tip:

Hit the market in the morning for the freshest baked goods, and if you're craving the best shawarma, head to the Muslim quarter of the souk – where they're known to be both delicious and budget-friendly.

Walking Tours in Jerusalem, Israel

Create Your Own Walk in Jerusalem

Creating your own self-guided walk in Jerusalem is easy and fun. Choose the city attractions that you want to see and a walk route map will be created just for you. You can even set your hotel as the start point of the walk.

Jerusalem City Gates Walking Tour

Historians believe that the Old City of Jerusalem probably came into being more than 4,500 years ago. The defensive wall around it features a number of gates built on the order of the Ottoman sultan Suleyman the Magnificent in the first half of the 16th century, each of which is an attraction in its own right. Until as recently as 1870, they were all closed from sunset to sunrise; nowadays, just... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Mount Zion Walking Tour

For those interested in religion and history, Mount Zion offers several unique sights that are situated in close proximity to each other. An important place for Christians, Jews as well as Muslims, it holds important constructions dating from the 20th century as well as a compound built by the Crusaders that marks the spot of both King David’s tomb and the Room of the Last Supper. How... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.0 Km or 0.6 Miles

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.0 Km or 0.6 Miles

Bethlehem Walking Tour

Perched on a hill at the edge of the Judaean Desert, Bethlehem has been known to the world, for more than two millennia, as the birthplace of Jesus Christ. The “star of Bethlehem” as well as Christmas carols and hymns are firmly associated with this ancient city in the West Bank, Palestine, and thus, for some visitors, the bustle of a modern city may come as a surprise.

Undoubtedly, the... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.5 Km or 0.9 Miles

Undoubtedly, the... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.5 Km or 0.9 Miles

Christian Quarter Walking Tour

One of the epicenters of worldwide Christianity, the Christian Quarter is the 2nd-largest of Jerusalem’s four ancient quarters. A fascinating place to stroll through, it covers the Old City’s northwestern part, just beyond Jaffa Gate – the traditional pilgrim’s entrance to Jerusalem and a prime destination for most visitors.

With its tangle of broad streets and winding, narrow alleys,... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.1 Km or 0.7 Miles

With its tangle of broad streets and winding, narrow alleys,... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.1 Km or 0.7 Miles

Mount Scopus Walking Tour

Dotted with many sightseeing places, Mount Scopus – translating as the “Observation Mount” from Greek – is a great place to get views over the whole Old City of Jerusalem on a nice day. The mount has been of major strategic importance since Roman times, with forces setting up camp here prior to laying the siege that culminated in the final Roman victory over Jerusalem around 70 AD.... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.3 Km or 1.4 Miles

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.3 Km or 1.4 Miles

Jewish Quarter Walking Tour

Entirely rebuilt in the 1980s after having been largely destroyed during the 1948 War, the Jewish Quarter is quite distinct from the rest of the Old City. Good signposting, spacious passageways, art galleries and a somewhat less buzzing atmosphere make the area a relaxing place to spend some time.

With its rebuilt residential buildings, some almost consider this area the "New... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.3 Km or 0.8 Miles

With its rebuilt residential buildings, some almost consider this area the "New... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.3 Km or 0.8 Miles

Useful Travel Guides for Planning Your Trip

16 Uniquely Israel Things to Buy in Jerusalem

Modern day Jerusalem is a mosaic of neighborhoods, reflecting different historical periods, cultures, and religions. The influx of repatriates in recent years has made the cultural and artisanal scene of the city even more colourful and diverse. To find your way through Jerusalem's intricate...

The Most Popular Cities

/ view all