Jerusalem Old City Walking Tour (Self Guided), Jerusalem

Jerusalem has been around long enough to see empires rise, fall, and try again. This is one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, shaped by faith, power, and a long rhythm of destruction followed by rebuilding. Archaeology traces settlement on the site of today's Jerusalem back to the Bronze Age, when it was just a modest Canaanite stronghold.

The city’s name tells a story of layers. In Hebrew tradition, Yerushalayim enters biblical texts, and later interpretation links it to two ideas brought together: Yireh, a place of divine presence, and Shalem, a place of peace. As centuries passed, Greek, Latin, and Arabic speakers adapted the name to their own languages, until it eventually settled into the English “Jerusalem.”

Around the 10th century BC, Jerusalem stepped onto a larger political stage as the capital of the Israelite kingdom under King David, with the First Temple traditionally attributed to his son Solomon. In 586 BC, Babylonian forces destroyed the city. Persian rule later allowed restoration, followed by Hellenistic influence after Alexander the Great, and then Roman control. That period ended dramatically in 70 AD, when the Romans destroyed the Second Temple and rebuilt Jerusalem as a Roman colony.

From the 4th century onward, Jerusalem became central to Christian worship, especially after the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built. In the 7th century, Islamic rule added another defining layer, making Jerusalem the third-holiest city in Islam and linking it to the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey. Crusaders, Mamluks, and Ottomans followed, each leaving marks that are still visible today. Ottoman rule from the 16th century gave the Old City much of its current form.

That Old City, enclosed by Ottoman walls, remains the heart of today's Jerusalem and has been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1981. Within a remarkably compact space divided into Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and Armenian quarters, it contains some of the world's most sacred sites to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Landmarks such as the Western Wall, the Temple Mount with the Al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre coexist alongside markets, residential streets, and pilgrimage routes like the Via Dolorosa.

To fully grasp Jerusalem’s depth and complexity, it must be experienced on foot, at an unhurried pace. This is a city that does not explain itself all at once. Take time to move through the Old City's winding routes, observe how its sacred and ordinary spaces intersect, and engage directly with a place where belief, memory, and daily life have intersected for thousands of years.

The city’s name tells a story of layers. In Hebrew tradition, Yerushalayim enters biblical texts, and later interpretation links it to two ideas brought together: Yireh, a place of divine presence, and Shalem, a place of peace. As centuries passed, Greek, Latin, and Arabic speakers adapted the name to their own languages, until it eventually settled into the English “Jerusalem.”

Around the 10th century BC, Jerusalem stepped onto a larger political stage as the capital of the Israelite kingdom under King David, with the First Temple traditionally attributed to his son Solomon. In 586 BC, Babylonian forces destroyed the city. Persian rule later allowed restoration, followed by Hellenistic influence after Alexander the Great, and then Roman control. That period ended dramatically in 70 AD, when the Romans destroyed the Second Temple and rebuilt Jerusalem as a Roman colony.

From the 4th century onward, Jerusalem became central to Christian worship, especially after the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built. In the 7th century, Islamic rule added another defining layer, making Jerusalem the third-holiest city in Islam and linking it to the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey. Crusaders, Mamluks, and Ottomans followed, each leaving marks that are still visible today. Ottoman rule from the 16th century gave the Old City much of its current form.

That Old City, enclosed by Ottoman walls, remains the heart of today's Jerusalem and has been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1981. Within a remarkably compact space divided into Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and Armenian quarters, it contains some of the world's most sacred sites to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Landmarks such as the Western Wall, the Temple Mount with the Al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre coexist alongside markets, residential streets, and pilgrimage routes like the Via Dolorosa.

To fully grasp Jerusalem’s depth and complexity, it must be experienced on foot, at an unhurried pace. This is a city that does not explain itself all at once. Take time to move through the Old City's winding routes, observe how its sacred and ordinary spaces intersect, and engage directly with a place where belief, memory, and daily life have intersected for thousands of years.

How it works: Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" from Apple App Store or Google Play Store to your mobile phone or tablet. The app turns your mobile device into a personal tour guide and its built-in GPS navigation functions guide you from one tour stop to next. The app works offline, so no data plan is needed when traveling abroad.

Jerusalem Old City Walking Tour Map

Guide Name: Jerusalem Old City Walking Tour

Guide Location: Israel » Jerusalem (See other walking tours in Jerusalem)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 13

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 5.0 Km or 3.1 Miles

Author: vickyc

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

Guide Location: Israel » Jerusalem (See other walking tours in Jerusalem)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 13

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 5.0 Km or 3.1 Miles

Author: vickyc

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

- Jaffa Gate

- The Citadel (Tower of David)

- David Street Arab Market (Shuk)

- Western (Wailing) Wall

- Al-Aqsa Mosque (Masjid al-Aqsa)

- Temple Mount

- Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra)

- Lions' Gate

- Churches of St. Anne

- Pools of Bethesda

- Ecce Homo Arch

- Via Dolorosa (Way of Sorrow)

- Damascus (Shechem) Gate

1) Jaffa Gate

Known in English as Jaffa Gate, this is Jerusalem's Old City’s busiest entrance—and it knows it. Indeed, this is where traffic, tour groups, taxis, and determined pedestrians funnel in from Mamilla and modern West Jerusalem.

From the outside, it looks broad and welcoming, but once you step inside, the passage quickly narrows and bends sharply. That awkward L-shaped turn is no accident. Built in 1538 under Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, the gate was engineered to slow down attackers and break their momentum. A stone inscription above the outer arch still records its precise construction date, just in case anyone doubts the planning.

Unlike most Old City gates, cars are allowed through here, thanks to an unusual episode in 1898. When Kaiser Wilhelm II arrived for a ceremonial visit, the Ottomans worried about an old belief that conquerors were expected to enter Jerusalem through this gate. Their solution was diplomatic engineering—a temporary breach cut into the wall beside the gate, so the Kaiser could ride in without triggering uncomfortable symbolism.

Fast-forward to 1917, and General Edmund Allenby made a point of doing the opposite. When British forces entered Jerusalem, Allenby dismounted and walked through the gate on foot, deliberately rejecting spectacle in favor of restraint.

The gate’s multiple names tell their own story. Sha’ar Yafo in Hebrew and Jaffa Gate in English recall the road leading to the Mediterranean port of Jaffa, long the arrival point for pilgrims and travelers. In Arabic, Bab al-Khalil points south instead, toward Hebron, known as Al-Khalil. One gate, three names, several directions—and a long memory of who entered, how, and why.

From the outside, it looks broad and welcoming, but once you step inside, the passage quickly narrows and bends sharply. That awkward L-shaped turn is no accident. Built in 1538 under Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, the gate was engineered to slow down attackers and break their momentum. A stone inscription above the outer arch still records its precise construction date, just in case anyone doubts the planning.

Unlike most Old City gates, cars are allowed through here, thanks to an unusual episode in 1898. When Kaiser Wilhelm II arrived for a ceremonial visit, the Ottomans worried about an old belief that conquerors were expected to enter Jerusalem through this gate. Their solution was diplomatic engineering—a temporary breach cut into the wall beside the gate, so the Kaiser could ride in without triggering uncomfortable symbolism.

Fast-forward to 1917, and General Edmund Allenby made a point of doing the opposite. When British forces entered Jerusalem, Allenby dismounted and walked through the gate on foot, deliberately rejecting spectacle in favor of restraint.

The gate’s multiple names tell their own story. Sha’ar Yafo in Hebrew and Jaffa Gate in English recall the road leading to the Mediterranean port of Jaffa, long the arrival point for pilgrims and travelers. In Arabic, Bab al-Khalil points south instead, toward Hebron, known as Al-Khalil. One gate, three names, several directions—and a long memory of who entered, how, and why.

2) The Citadel (Tower of David) (must see)

Just inside Jaffa Gate rises the Citadel, better known today as the Tower of David—a place where Jerusalem’s history is stacked quite literally in stone. Careful excavation has peeled the site back layer by layer, so as you move through it, you’re also moving through time. The experience easily stretches over a couple of hours, especially if you follow the story indoors, where archaeology and narrative are woven together into a clear, chronological portrait of the city.

The Citadel occupies the western hill of the Old City, a strategic high point fortified repeatedly since the 2nd century BC. Early defenses were expanded dramatically by Herod the Great, who reinforced the Hasmonean walls with three massive towers. Only one of them—the Phasael Tower—still stands, but it does plenty of heavy lifting. Later, during the Byzantine period, a historical mix-up led locals to believe this was King David’s palace, giving the complex its enduring name.

Power changed hands, and so did the Citadel. Muslim rulers, Crusaders, and later the Mamluks reshaped it until its basic form was fixed in 1310 under Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad. In the 16th century, Suleiman the Magnificent added a grand eastern gateway and an open square, while the minaret—built in the 17th century—rose to become one of Jerusalem’s most recognizable silhouettes.

Climb the Phasael Tower in the Citadel’s northeast corner, and the reward is perspective, in every sense. Below you lie the excavations; beyond them, the Old City; further still, the hills stretching south and west. Along the way, plaques help decode what you’re seeing—Hasmonean walls, Roman cisterns, and Umayyad fortifications that once held firm against Crusader forces in 1099.

And when night falls, stick around. A 45-minute sound-and-light show transforms the Citadel into a moving timeline of Jerusalem’s past—dramatic, immersive, and very popular. Book ahead, or risk watching history unfold from the outside.

The Citadel occupies the western hill of the Old City, a strategic high point fortified repeatedly since the 2nd century BC. Early defenses were expanded dramatically by Herod the Great, who reinforced the Hasmonean walls with three massive towers. Only one of them—the Phasael Tower—still stands, but it does plenty of heavy lifting. Later, during the Byzantine period, a historical mix-up led locals to believe this was King David’s palace, giving the complex its enduring name.

Power changed hands, and so did the Citadel. Muslim rulers, Crusaders, and later the Mamluks reshaped it until its basic form was fixed in 1310 under Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad. In the 16th century, Suleiman the Magnificent added a grand eastern gateway and an open square, while the minaret—built in the 17th century—rose to become one of Jerusalem’s most recognizable silhouettes.

Climb the Phasael Tower in the Citadel’s northeast corner, and the reward is perspective, in every sense. Below you lie the excavations; beyond them, the Old City; further still, the hills stretching south and west. Along the way, plaques help decode what you’re seeing—Hasmonean walls, Roman cisterns, and Umayyad fortifications that once held firm against Crusader forces in 1099.

And when night falls, stick around. A 45-minute sound-and-light show transforms the Citadel into a moving timeline of Jerusalem’s past—dramatic, immersive, and very popular. Book ahead, or risk watching history unfold from the outside.

3) David Street Arab Market (Shuk)

Sliding downhill from the Jaffa Gate, you'll find yourself on David Street, a narrow pedestrian artery marking the line between the Christian Quarter on one side and the Armenian Quarter on the other. Thanks to its location—and its undeniable charm—it pulls in just about everyone at once: Jewish worshipers heading toward the Western Wall, Christian pilgrims bound for the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Muslims moving uphill toward the Temple Mount, and plenty of visitors simply trying to take it all in without losing their footing.

Cars don’t stand a chance here. The street is barely wide enough for foot traffic, with just enough room for the occasional three-wheeled cart to squeeze past. This stretch forms the backbone of Jerusalem’s most famous market area, the Arab Market, or Arab Shuk, which branches into several distinct sections.

In the Christian Quarter, the focus leans heavily toward visitors, with stalls filled with Christian-themed souvenirs, icons, and keepsakes. Mixed in are a few solid bakeries and modest supermarkets that still serve the residents who live above and behind the shopfronts.

One quick market survival tip before you dive in. Bargaining is expected—and often enjoyed—when it comes to souvenirs and household items. Fresh produce, however, plays by different rules. Fruit and vegetable stalls usually work with fixed prices, sometimes written in Arabic, sometimes simply understood. Trying to negotiate over tomatoes may earn you a smile, but it can just as easily cross into an awkward territory.

Just browse, buy, and move along—and let the rhythm of the street do the rest of the talking.

Cars don’t stand a chance here. The street is barely wide enough for foot traffic, with just enough room for the occasional three-wheeled cart to squeeze past. This stretch forms the backbone of Jerusalem’s most famous market area, the Arab Market, or Arab Shuk, which branches into several distinct sections.

In the Christian Quarter, the focus leans heavily toward visitors, with stalls filled with Christian-themed souvenirs, icons, and keepsakes. Mixed in are a few solid bakeries and modest supermarkets that still serve the residents who live above and behind the shopfronts.

One quick market survival tip before you dive in. Bargaining is expected—and often enjoyed—when it comes to souvenirs and household items. Fresh produce, however, plays by different rules. Fruit and vegetable stalls usually work with fixed prices, sometimes written in Arabic, sometimes simply understood. Trying to negotiate over tomatoes may earn you a smile, but it can just as easily cross into an awkward territory.

Just browse, buy, and move along—and let the rhythm of the street do the rest of the talking.

4) Western (Wailing) Wall (must see)

The Western Wall—also known as the Wailing Wall, the Place of Weeping, or the Buraq Wall—is not a standalone monument but a surviving fragment of the massive retaining wall that once supported the Temple Mount. It dates back to 19 BC, when Herod the Great decided that the sacred platform needed more space and a lot more engineering. The solution was to expand the mount artificially and build enormous stone walls to hold everything in place. What you’re looking at is structural support that quietly became one of the most charged religious sites on earth.

From its foundation, the wall rises about 100 feet, though only around 60 feet are visible today. Of the 45 stone layers stacked here, just 28 are exposed. The lowest seven courses come straight from Herod’s time. Four more were added under the Umayyad Caliphate around the 7th century, another 14 during Ottoman rule in the 1860s, and the final three layers were completed in the 1920s under the Mufti of Jerusalem.

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, nothing has been added. The wall, for once in Jerusalem’s history, has been left exactly as it is.

Then there’s the scale. Some of these limestone blocks weigh between two and eight tons, and one stone near Wilson’s Arch tips the scales at an almost unbelievable 570 tons. Even by ancient standards, this was an extraordinary feat of planning, labor, and sheer stubborn ambition.

The wall has been a place of Jewish prayer since at least the 4th century AD and is considered sacred because of its proximity to the Temple Mount. The term “wailing” comes from the tradition of mourning the destruction of the Temple.

Today, men and women pray in separate sections, especially during the Sabbath, from Friday evening to Saturday evening. You’ll also notice folded notes tucked into the stones—written prayers left by visitors. They’re collected regularly and buried respectfully on the Mount of Olives.

A practical note before you approach: bring valid ID, expect security checks, dress modestly, and remember that photography is not permitted during the Sabbath. Entry, however, is free—no ticket required to stand before two thousand years of layered history...

From its foundation, the wall rises about 100 feet, though only around 60 feet are visible today. Of the 45 stone layers stacked here, just 28 are exposed. The lowest seven courses come straight from Herod’s time. Four more were added under the Umayyad Caliphate around the 7th century, another 14 during Ottoman rule in the 1860s, and the final three layers were completed in the 1920s under the Mufti of Jerusalem.

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, nothing has been added. The wall, for once in Jerusalem’s history, has been left exactly as it is.

Then there’s the scale. Some of these limestone blocks weigh between two and eight tons, and one stone near Wilson’s Arch tips the scales at an almost unbelievable 570 tons. Even by ancient standards, this was an extraordinary feat of planning, labor, and sheer stubborn ambition.

The wall has been a place of Jewish prayer since at least the 4th century AD and is considered sacred because of its proximity to the Temple Mount. The term “wailing” comes from the tradition of mourning the destruction of the Temple.

Today, men and women pray in separate sections, especially during the Sabbath, from Friday evening to Saturday evening. You’ll also notice folded notes tucked into the stones—written prayers left by visitors. They’re collected regularly and buried respectfully on the Mount of Olives.

A practical note before you approach: bring valid ID, expect security checks, dress modestly, and remember that photography is not permitted during the Sabbath. Entry, however, is free—no ticket required to stand before two thousand years of layered history...

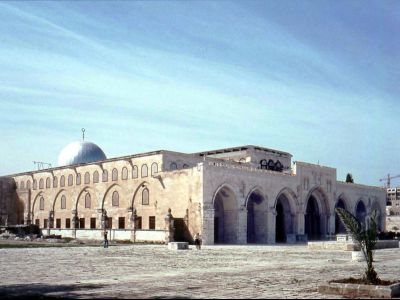

5) Al-Aqsa Mosque (Masjid al-Aqsa)

Masjid al-Aqsa—literally “the Farthest Mosque”—doesn’t try to outshine its flashier neighbor, the Dome of the Rock. It’s more restrained, more grounded, and very much aware of its own long memory. Standing on the Temple Mount, it marks the site traditionally linked to the first mosque built in Jerusalem in 638, connected to the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey, which placed this spot firmly into Islamic sacred geography.

History, however, has rarely left Al-Aqsa alone. Earthquakes, fires, and political upheavals have damaged it repeatedly, turning rebuilding into a recurring theme rather than a one-off event.

During the Crusader period, subtlety went out the window. The mosque was converted into a church, a cross was planted on its dome, and the underground vaults were repurposed as stables for Crusader horses—hence the enduring nickname, “Solomon’s Stables.” The Knights Templar order, founded in 1118, even borrowed their name from this complex, which the Crusaders confidently labeled the Templum, as if the past could be neatly reassigned.

That phase didn’t last, though. When Saladin retook Jerusalem, the Christian alterations were removed, and Al-Aqsa was restored as a mosque. The interior was carefully renewed, including the installation of an elaborate cedarwood minbar (pulpit) brought from Damascus, richly inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl. Although that pulpit was lost in a devastating fire in 1969, much of the mosque’s character survived—its mosaics, rose window, and original columns still quietly holding their ground.

What you see today is largely the result of 20th-century restoration, but don’t mistake “modern” for “plain.” Inside are seven aisles, marble columns, and 121 stained-glass windows that soften the light and slow the pace. Entry for non-Muslims is restricted, yet even from the outside, Al-Aqsa speaks volumes. It’s a building that doesn’t shout its importance—it lets history do the talking.

History, however, has rarely left Al-Aqsa alone. Earthquakes, fires, and political upheavals have damaged it repeatedly, turning rebuilding into a recurring theme rather than a one-off event.

During the Crusader period, subtlety went out the window. The mosque was converted into a church, a cross was planted on its dome, and the underground vaults were repurposed as stables for Crusader horses—hence the enduring nickname, “Solomon’s Stables.” The Knights Templar order, founded in 1118, even borrowed their name from this complex, which the Crusaders confidently labeled the Templum, as if the past could be neatly reassigned.

That phase didn’t last, though. When Saladin retook Jerusalem, the Christian alterations were removed, and Al-Aqsa was restored as a mosque. The interior was carefully renewed, including the installation of an elaborate cedarwood minbar (pulpit) brought from Damascus, richly inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl. Although that pulpit was lost in a devastating fire in 1969, much of the mosque’s character survived—its mosaics, rose window, and original columns still quietly holding their ground.

What you see today is largely the result of 20th-century restoration, but don’t mistake “modern” for “plain.” Inside are seven aisles, marble columns, and 121 stained-glass windows that soften the light and slow the pace. Entry for non-Muslims is restricted, yet even from the outside, Al-Aqsa speaks volumes. It’s a building that doesn’t shout its importance—it lets history do the talking.

6) Temple Mount (must see)

Known to Muslims as Al-Haram ash-Sharif, meaning “the Noble Sanctuary,” this vast stone platform in the southeastern corner of the Old City has been holding Jerusalem’s attention for a very long time. According to both Jewish and Muslim tradition, this is the place where Abraham was prepared to sacrifice his son. Jewish tradition also identifies it as the site of the First Temple, built by Solomon in the 10th century BC, destroyed by the Babylonians in 587 BC, and centuries later, followed by the Second Temple.

That second sanctuary didn’t just sit here quietly either. In the 1st century BC, Herod the Great dramatically reshaped the area, expanding the Temple complex by enclosing a natural hill with massive retaining walls and filling the space to create the platform you see today. It was here, according to the Gospels, that Jesus overturned the tables of merchants and money-changers. The drama escalated in 70 AD, when Roman forces destroyed the Second Temple after a brutal siege. Ancient historian Josephus describes a city pushed to the extremes, marked by famine, violence, and collapse.

Today, the skyline is dominated by the golden dome of the Dome of the Rock, but the platform holds far more than its most famous landmark. Scattered across the enclosure are layers of Islamic architecture from the Umayyad, Ayyubid, Mamluk, and Ottoman periods—grammar schools, madrasas, arcades, and smaller shrines that quietly trace centuries of scholarship and rule. Nearby, stands the Al-Aqsa Mosque, one of Islam’s holiest sites.

Access here is carefully regulated. Certain areas are closed off, and non-Muslims may enter only through the Moors’ Gate, with interior access to the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa restricted. This is not a place to rush. Pause, look around, and remember: few spaces on Earth carry so many stories, beliefs, and turning points within a single stretch of stone.

That second sanctuary didn’t just sit here quietly either. In the 1st century BC, Herod the Great dramatically reshaped the area, expanding the Temple complex by enclosing a natural hill with massive retaining walls and filling the space to create the platform you see today. It was here, according to the Gospels, that Jesus overturned the tables of merchants and money-changers. The drama escalated in 70 AD, when Roman forces destroyed the Second Temple after a brutal siege. Ancient historian Josephus describes a city pushed to the extremes, marked by famine, violence, and collapse.

Today, the skyline is dominated by the golden dome of the Dome of the Rock, but the platform holds far more than its most famous landmark. Scattered across the enclosure are layers of Islamic architecture from the Umayyad, Ayyubid, Mamluk, and Ottoman periods—grammar schools, madrasas, arcades, and smaller shrines that quietly trace centuries of scholarship and rule. Nearby, stands the Al-Aqsa Mosque, one of Islam’s holiest sites.

Access here is carefully regulated. Certain areas are closed off, and non-Muslims may enter only through the Moors’ Gate, with interior access to the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa restricted. This is not a place to rush. Pause, look around, and remember: few spaces on Earth carry so many stories, beliefs, and turning points within a single stretch of stone.

7) Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra)

The Dome of the Rock doesn’t ease into the conversation—it announces itself. That golden dome, the deep blues, the almost unnerving balance of proportions all signal that this is architecture designed to be seen, remembered, and quietly debated. Commissioned in the late 7th century AD by Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, the building made a clear statement: Islam belonged at the very center of Jerusalem’s sacred landscape, standing visually and symbolically alongside monuments like the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Despite what many assume, this is not a mosque. There’s no formal prayer hall, no qibla wall directing worshipers toward Mecca. Instead, the structure is a shrine, built to frame and protect a single object of immense significance: the exposed rock at its center. According to tradition, this is the place where Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son, and it also rises from what remained of Herod the Great’s Second Temple platform. Abd al-Malik chose not to build over that history, but around it, letting the rock remain both visible and central.

At a closer look, the surface becomes a lesson in precision and restraint. Marble panels line the lower walls, while bands of glazed blue and green tiles carry Quranic inscriptions, interlaced with geometric and floral designs. Much of the exterior decoration dates to the 16th century, when Suleiman the Magnificent ordered a major renovation that fixed the Dome’s visual identity for centuries to come.

The dome itself has had a practical life as well as a symbolic one. In the 1960s, its original lead covering—heavy and problematic—was replaced with anodized aluminum, later finished in gold. It’s a reminder that even icons need maintenance. Yet through repairs, restorations, and reinterpretations, the Dome of the Rock has never lost its role: not just as a landmark of Jerusalem, but as a carefully calculated statement of faith, history, and permanence—still holding the skyline, and the conversation, in perfect balance.

Despite what many assume, this is not a mosque. There’s no formal prayer hall, no qibla wall directing worshipers toward Mecca. Instead, the structure is a shrine, built to frame and protect a single object of immense significance: the exposed rock at its center. According to tradition, this is the place where Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son, and it also rises from what remained of Herod the Great’s Second Temple platform. Abd al-Malik chose not to build over that history, but around it, letting the rock remain both visible and central.

At a closer look, the surface becomes a lesson in precision and restraint. Marble panels line the lower walls, while bands of glazed blue and green tiles carry Quranic inscriptions, interlaced with geometric and floral designs. Much of the exterior decoration dates to the 16th century, when Suleiman the Magnificent ordered a major renovation that fixed the Dome’s visual identity for centuries to come.

The dome itself has had a practical life as well as a symbolic one. In the 1960s, its original lead covering—heavy and problematic—was replaced with anodized aluminum, later finished in gold. It’s a reminder that even icons need maintenance. Yet through repairs, restorations, and reinterpretations, the Dome of the Rock has never lost its role: not just as a landmark of Jerusalem, but as a carefully calculated statement of faith, history, and permanence—still holding the skyline, and the conversation, in perfect balance.

8) Lions' Gate

This entrance in Jerusalem’s eastern wall answers to several names, which already tells you it has lived a busy life. Most visitors know it as the Lions’ Gate, thanks to the pair of stone beasts guarding the doorway. Christians, meanwhile, often call it Saint Stephen’s Gate, after the first Christian martyr, who was stoned outside the city. His burial place originally lay near Damascus Gate, but was later shifted here, making life a little easier for generations of pilgrims.

Arabic names add more layers to the story. One is Bab al-Ghor, or “Jordan Valley Gate,” pointing east toward the land below. Another links the gate to the Virgin Mary, believed by tradition to have been born nearby. Then there’s Meshikuli, a term best translated as “wicket”—a reminder that gates were once part of a defensive system, not a photo opportunity. Through openings like this, watchful eyes scanned the horizon, ready to respond to anything approaching, sometimes with less-than-hospitable methods, involving boiling oil.

The animals themselves come with their own debate. Officially, they’re lions, though some insist they’re panthers. One tradition connects them to the Mamluk sultan Baybars I, whose emblem they resemble. According to legend, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent ordered them placed here to celebrate driving the Crusaders from the region. Another story claims the decision followed a dream in which Suleiman was threatened by lions if he failed to rebuild Jerusalem’s walls—a reminder that urban planning has always had its anxieties...

What’s remarkable is how little the gate has changed. Unlike much of the Old City, it has never been restored. It still does its job quietly, funneling crowds in and out—especially on Fridays, when worshipers stream toward the nearby Al-Aqsa Mosque. Stand here for a moment, and you’ll see exactly what this gate has always done best: connect names, beliefs, and centuries of history in one narrow opening.

Arabic names add more layers to the story. One is Bab al-Ghor, or “Jordan Valley Gate,” pointing east toward the land below. Another links the gate to the Virgin Mary, believed by tradition to have been born nearby. Then there’s Meshikuli, a term best translated as “wicket”—a reminder that gates were once part of a defensive system, not a photo opportunity. Through openings like this, watchful eyes scanned the horizon, ready to respond to anything approaching, sometimes with less-than-hospitable methods, involving boiling oil.

The animals themselves come with their own debate. Officially, they’re lions, though some insist they’re panthers. One tradition connects them to the Mamluk sultan Baybars I, whose emblem they resemble. According to legend, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent ordered them placed here to celebrate driving the Crusaders from the region. Another story claims the decision followed a dream in which Suleiman was threatened by lions if he failed to rebuild Jerusalem’s walls—a reminder that urban planning has always had its anxieties...

What’s remarkable is how little the gate has changed. Unlike much of the Old City, it has never been restored. It still does its job quietly, funneling crowds in and out—especially on Fridays, when worshipers stream toward the nearby Al-Aqsa Mosque. Stand here for a moment, and you’ll see exactly what this gate has always done best: connect names, beliefs, and centuries of history in one narrow opening.

9) Churches of St. Anne (must see)

Just inside Lions' Gate, tucked within a quiet walled compound, you’ll find not one but two Churches of Saint Anne—both dedicated to Anne, traditionally known as the mother of the Virgin Mary. Closest to the gate stands the Greek Orthodox church. It is modest in scale and gently atmospheric, with a small cave-like chapel that tradition associates with Mary’s birth. Below, a stairway leads to the tombs attributed to her parents, Saints Anne and Joachim. The doors open at set hours, and a small donation is the customary way of saying thanks.

Right next door is the 12th-century Greek Catholic church, a Crusader-era building that proves simplicity can be quietly impressive. Its architecture mixes Romanesque clarity with Middle Eastern details—pointed arches and a fluted window frame that would later travel west with the Crusaders. Inside, the space is spare and luminous, with smooth columns and clean vaults that draw the eye upward. Then there’s the sound: the acoustics are so precise that the pilgrim groups often come here to sing rather than to look, letting hymns linger in the air long after the final note.

A set of steps descends to an older crypt, where Byzantine columns and mosaic fragments hint at even earlier layers of worship. Catholic tradition places Mary’s birth here, though today the site is presented with thoughtful restraint rather than firm claims—history speaking softly instead of shouting...

Before you move on, pause for two small pleasures. First, notice the building’s asymmetry—count the steps on either side, and you’ll see it. Second, step into the adjoining garden, a calm pocket of green that feels almost unreal this close to the Old City’s busiest paths. It’s a gentle reminder that in Jerusalem, even the quiet corners carry centuries of stories—and sometimes, they whisper them.

Right next door is the 12th-century Greek Catholic church, a Crusader-era building that proves simplicity can be quietly impressive. Its architecture mixes Romanesque clarity with Middle Eastern details—pointed arches and a fluted window frame that would later travel west with the Crusaders. Inside, the space is spare and luminous, with smooth columns and clean vaults that draw the eye upward. Then there’s the sound: the acoustics are so precise that the pilgrim groups often come here to sing rather than to look, letting hymns linger in the air long after the final note.

A set of steps descends to an older crypt, where Byzantine columns and mosaic fragments hint at even earlier layers of worship. Catholic tradition places Mary’s birth here, though today the site is presented with thoughtful restraint rather than firm claims—history speaking softly instead of shouting...

Before you move on, pause for two small pleasures. First, notice the building’s asymmetry—count the steps on either side, and you’ll see it. Second, step into the adjoining garden, a calm pocket of green that feels almost unreal this close to the Old City’s busiest paths. It’s a gentle reminder that in Jerusalem, even the quiet corners carry centuries of stories—and sometimes, they whisper them.

10) Pools of Bethesda

Just beside the serene Saint Anne’s Church, history takes a sharp turn underground. Here lie the Pools of Bethesda, built around 200 BC to supply water to the Temple—practical infrastructure with a spiritual reputation. According to the Gospel of Saint John, these waters were believed to heal, and it’s here that Jesus is said to have cured a man who had been ill for 38 years. Not bad credentials for a water system...

Archaeology fills in the background details. Excavations uncovered the remains of five porticoes, matching the biblical description, along with nearby caves that the Romans converted into bathing areas. In Roman times, this was less a quiet sanctuary and more a full-scale healing complex, crowded with people hoping the waters might change their fortunes. The Romans later added their own layer, constructing a 3rd-century temple dedicated to Serapis (the god of the underworld, healing, fertility, and the heavens), which was eventually replaced by a Byzantine basilica—because in Jerusalem, even sacred real estate gets reused.

Today, a raised walkway lets you circle the pools and peer down into centuries of engineering, ritual, and belief. You can descend into a Roman cistern, trace the outlines of walls and arches, and see how one site absorbed pagan worship, Christian tradition, and urban infrastructure without ever fully pressing reset. A detailed plan helps keep the centuries straight.

There’s also a small on-site museum displaying finds from the excavations—quiet, modest, and usually open only by appointment. But even without it, the Pools of Bethesda tell their story clearly enough: a place where water, faith, and history have been flowing together for more than two thousand years.

Archaeology fills in the background details. Excavations uncovered the remains of five porticoes, matching the biblical description, along with nearby caves that the Romans converted into bathing areas. In Roman times, this was less a quiet sanctuary and more a full-scale healing complex, crowded with people hoping the waters might change their fortunes. The Romans later added their own layer, constructing a 3rd-century temple dedicated to Serapis (the god of the underworld, healing, fertility, and the heavens), which was eventually replaced by a Byzantine basilica—because in Jerusalem, even sacred real estate gets reused.

Today, a raised walkway lets you circle the pools and peer down into centuries of engineering, ritual, and belief. You can descend into a Roman cistern, trace the outlines of walls and arches, and see how one site absorbed pagan worship, Christian tradition, and urban infrastructure without ever fully pressing reset. A detailed plan helps keep the centuries straight.

There’s also a small on-site museum displaying finds from the excavations—quiet, modest, and usually open only by appointment. But even without it, the Pools of Bethesda tell their story clearly enough: a place where water, faith, and history have been flowing together for more than two thousand years.

11) Ecce Homo Arch

Stretching across the Via Dolorosa, this arch looks quietly theatrical—and it has earned the role. Its story begins in 70 AD, when the Romans threw it up as part of a military ramp aimed at the Antonia Fortress, where Jewish rebels were holding out. A few decades later, after crushing the Second Jewish War, the Romans rebuilt Jerusalem in 135 AD and gave the arch a victory makeover: one large central opening flanked by two smaller arches. The main bay still spans the street here, just west of the entrance to the Lithostratos, better known as the “Pavement of Justice.”

One of those side arches didn’t vanish—it simply changed address. Today, it survives indoors, folded neatly into the Convent of the Sisters of Zion, built in the 1860s. Beneath the convent lies the Struthion Pool, an ancient reservoir designed to catch rainwater from the surrounding rooftops. Christian tradition places a dramatic moment here: the stone pavement above the pool is said to be where Pontius Pilate presented Jesus to the crowd with the words “Ecce homo”—“Behold the man.” Archaeology, however, plays the spoiler. The pavement dates to the 2nd century AD, from the reign of Emperor Hadrian, making it a later Roman addition rather than a firsthand witness to the trial.

Looking closely at the stone within the railed section, you will spot etched markings—circles and lines that historians believe were scratched by bored Roman guards, possibly for games played while on duty. It’s a small, human detail amid the heavy symbolism.

Just nearby, beside the Third Station, a building belonging to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate bears a plaque identifying it as the Prison of Jesus and Barabbas. That label only appeared in 1911, and scholars are unconvinced. More likely, this was once a stable tied to the Antonia Fortress—less drama, more logistics. Indeed, in Jerusalem, even the stones argue back...

One of those side arches didn’t vanish—it simply changed address. Today, it survives indoors, folded neatly into the Convent of the Sisters of Zion, built in the 1860s. Beneath the convent lies the Struthion Pool, an ancient reservoir designed to catch rainwater from the surrounding rooftops. Christian tradition places a dramatic moment here: the stone pavement above the pool is said to be where Pontius Pilate presented Jesus to the crowd with the words “Ecce homo”—“Behold the man.” Archaeology, however, plays the spoiler. The pavement dates to the 2nd century AD, from the reign of Emperor Hadrian, making it a later Roman addition rather than a firsthand witness to the trial.

Looking closely at the stone within the railed section, you will spot etched markings—circles and lines that historians believe were scratched by bored Roman guards, possibly for games played while on duty. It’s a small, human detail amid the heavy symbolism.

Just nearby, beside the Third Station, a building belonging to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate bears a plaque identifying it as the Prison of Jesus and Barabbas. That label only appeared in 1911, and scholars are unconvinced. More likely, this was once a stable tied to the Antonia Fortress—less drama, more logistics. Indeed, in Jerusalem, even the stones argue back...

12) Via Dolorosa (Way of Sorrow) (must see)

Via Dolorosa—literally the “Way of Sorrow”—is the route traditionally associated with the final walk of Jesus Christ, from the judgment of Pontius Pilate to Golgotha. Today, this short but intense stretch of street threads its way through the Muslim Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City, beginning near the Madrasa al-Omariya, not far from the Lions' Gate, and ending inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In total, the route runs for roughly half a kilometer—compact in distance, immense in meaning...

Along the way are the 14 Stations of the Cross, each marking a moment from the Gospel narrative. While the tradition they represent is ancient, many of the stations themselves were formalized only in the 18th and 19th centuries. Look for the understated black iron plaques with Roman numerals: they are easy to miss amid shopfronts, doorways, and everyday street life. That contrast is part of the experience—sacred memory unfolding in the middle of a living city.

On Fridays, the route takes on a more solemn rhythm when Franciscan friars retrace the path in procession, continuing a tradition they have maintained as custodians of key Christian holy sites since the 14th century. The timing is deliberate, echoing the hour associated with the Crucifixion, and the atmosphere shifts noticeably, as prayers replace street noise, even if only briefly.

A practical note for your feet and focus: the stone paving can be slick, especially after rain, and the route includes steps and uneven slopes. Crowds ebb and flow without warning. So, keep your balance, keep your awareness, and keep your eyes up.

Beyond its religious importance, the Via Dolorosa offers fragments of architecture, artwork, and street life that reward close attention. This is not a corridor sealed in time—it’s a passage where devotion, history, and daily routine overlap, step by step.

Along the way are the 14 Stations of the Cross, each marking a moment from the Gospel narrative. While the tradition they represent is ancient, many of the stations themselves were formalized only in the 18th and 19th centuries. Look for the understated black iron plaques with Roman numerals: they are easy to miss amid shopfronts, doorways, and everyday street life. That contrast is part of the experience—sacred memory unfolding in the middle of a living city.

On Fridays, the route takes on a more solemn rhythm when Franciscan friars retrace the path in procession, continuing a tradition they have maintained as custodians of key Christian holy sites since the 14th century. The timing is deliberate, echoing the hour associated with the Crucifixion, and the atmosphere shifts noticeably, as prayers replace street noise, even if only briefly.

A practical note for your feet and focus: the stone paving can be slick, especially after rain, and the route includes steps and uneven slopes. Crowds ebb and flow without warning. So, keep your balance, keep your awareness, and keep your eyes up.

Beyond its religious importance, the Via Dolorosa offers fragments of architecture, artwork, and street life that reward close attention. This is not a corridor sealed in time—it’s a passage where devotion, history, and daily routine overlap, step by step.

13) Damascus (Shechem) Gate

Easily spotted—and impossible to ignore—Damascus Gate announces itself long before you reach it. This is the busiest, loudest, and most theatrical entrance to the Old City’s eastern side, where daily life spills out in every direction. Architecturally, it’s also the most heavily fortified of Jerusalem’s original seven gates. Battlements line the top, loopholes puncture the walls, and sturdy turrets flank the entrance.

As for that ominous opening above the gateway—once upon a time, it wasn’t decorative but was used to drop boiling oil or other unwelcome surprises on attackers. And just in case anyone made it inside, the passageway forces a sharp double turn, designed to slow invaders down at exactly the wrong moment.

The gate takes its familiar name from Damascus, the Syrian capital roughly 220 kilometers to the north, marking the route this road once led toward. Built between 1537 and 1542 under the watchful eye of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, it has changed remarkably little since. In Arabic, it’s known as Bab el-Amud, the “Gate of the Column,” likely referring to a towering column topped with a statue of Emperor Hadrian that once stood nearby, asserting Roman authority over the city.

At a closer look, the layers begin to pile up. The gate sits directly above the remains of a Roman predecessor, with Crusader, medieval, and Ottoman history stacked almost vertically. Just outside, steps lead down to archaeological excavations where fragments of a Crusader chapel, a medieval roadway, and traces of Rome’s Tenth Legion come into view.

Inside, a surviving Roman arch leads into the Roman Square Excavations, where the original plaza still preserves a carved stone gaming board—indeed, even imperial soldiers needed a break... This spot also marks the start of the Roman Cardo, the city’s ancient main street, while a hologram in the plaza recreates Hadrian’s long-lost column.

One last practical note: this is also where the Ramparts Walk begins, sending you along the city walls toward Lions’ Gate in one direction, or Jaffa Gate in the other—Jerusalem history, literally at your feet...

As for that ominous opening above the gateway—once upon a time, it wasn’t decorative but was used to drop boiling oil or other unwelcome surprises on attackers. And just in case anyone made it inside, the passageway forces a sharp double turn, designed to slow invaders down at exactly the wrong moment.

The gate takes its familiar name from Damascus, the Syrian capital roughly 220 kilometers to the north, marking the route this road once led toward. Built between 1537 and 1542 under the watchful eye of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, it has changed remarkably little since. In Arabic, it’s known as Bab el-Amud, the “Gate of the Column,” likely referring to a towering column topped with a statue of Emperor Hadrian that once stood nearby, asserting Roman authority over the city.

At a closer look, the layers begin to pile up. The gate sits directly above the remains of a Roman predecessor, with Crusader, medieval, and Ottoman history stacked almost vertically. Just outside, steps lead down to archaeological excavations where fragments of a Crusader chapel, a medieval roadway, and traces of Rome’s Tenth Legion come into view.

Inside, a surviving Roman arch leads into the Roman Square Excavations, where the original plaza still preserves a carved stone gaming board—indeed, even imperial soldiers needed a break... This spot also marks the start of the Roman Cardo, the city’s ancient main street, while a hologram in the plaza recreates Hadrian’s long-lost column.

One last practical note: this is also where the Ramparts Walk begins, sending you along the city walls toward Lions’ Gate in one direction, or Jaffa Gate in the other—Jerusalem history, literally at your feet...

Walking Tours in Jerusalem, Israel

Create Your Own Walk in Jerusalem

Creating your own self-guided walk in Jerusalem is easy and fun. Choose the city attractions that you want to see and a walk route map will be created just for you. You can even set your hotel as the start point of the walk.

Following Steps of Jesus Walking Tour

Considered for centuries to be the center of the universe, Jerusalem is where the most famous figure in history, Jesus of Nazareth, fulfilled his divine mission by carrying a cross from the place of Pontius Pilate’s sentencing to Golgotha where he was crucified. This self-guided tour will retrace the steps of Jesus, allowing you to see what many consider some of the holiest places on our planet.... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Mount of Olives Walking Tour

Aside from affording great views over the Old City, the Mount of Olives is home to half a dozen major sites of the Christian faith along with the oldest Jewish burial ground in the world. Considered a holy spot by many, it is associated with numerous events in Jesus’ life including ascending to Heaven and teaching his disciples the Lord’s Prayer.

The following self-guided walking tour will... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.7 Km or 1.1 Miles

The following self-guided walking tour will... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.7 Km or 1.1 Miles

Jewish Quarter Walking Tour

Entirely rebuilt in the 1980s after having been largely destroyed during the 1948 War, the Jewish Quarter is quite distinct from the rest of the Old City. Good signposting, spacious passageways, art galleries and a somewhat less buzzing atmosphere make the area a relaxing place to spend some time.

With its rebuilt residential buildings, some almost consider this area the "New... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.3 Km or 0.8 Miles

With its rebuilt residential buildings, some almost consider this area the "New... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.3 Km or 0.8 Miles

Mount Scopus Walking Tour

Dotted with many sightseeing places, Mount Scopus – translating as the “Observation Mount” from Greek – is a great place to get views over the whole Old City of Jerusalem on a nice day. The mount has been of major strategic importance since Roman times, with forces setting up camp here prior to laying the siege that culminated in the final Roman victory over Jerusalem around 70 AD.... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.3 Km or 1.4 Miles

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.3 Km or 1.4 Miles

Christian Quarter Walking Tour

One of the epicenters of worldwide Christianity, the Christian Quarter is the 2nd-largest of Jerusalem’s four ancient quarters. A fascinating place to stroll through, it covers the Old City’s northwestern part, just beyond Jaffa Gate – the traditional pilgrim’s entrance to Jerusalem and a prime destination for most visitors.

With its tangle of broad streets and winding, narrow alleys,... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.1 Km or 0.7 Miles

With its tangle of broad streets and winding, narrow alleys,... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.1 Km or 0.7 Miles

Jerusalem City Gates Walking Tour

Historians believe that the Old City of Jerusalem probably came into being more than 4,500 years ago. The defensive wall around it features a number of gates built on the order of the Ottoman sultan Suleyman the Magnificent in the first half of the 16th century, each of which is an attraction in its own right. Until as recently as 1870, they were all closed from sunset to sunrise; nowadays, just... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.7 Km or 2.3 Miles

Useful Travel Guides for Planning Your Trip

16 Uniquely Israel Things to Buy in Jerusalem

Modern day Jerusalem is a mosaic of neighborhoods, reflecting different historical periods, cultures, and religions. The influx of repatriates in recent years has made the cultural and artisanal scene of the city even more colourful and diverse. To find your way through Jerusalem's intricate...

The Most Popular Cities

/ view all