Audio Guide: Sofia Introduction Walking Tour (Self Guided), Sofia

Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria, is one of Europe’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, with archaeological traces of settlement dating back at least 7,000 years. Its fertile valley, abundant mineral springs, and position on major east–west and north–south routes made it a natural crossroads for ancient peoples.

The Thracian tribe Serdi established a settlement here in the 1st millennium BCE, giving rise to the city’s early name Serdica. When the Roman Empire expanded into the region in the 1st century CE, Serdica became an important provincial centre, protected by strong walls and adorned with public buildings, baths, a forum, and an amphitheatre.

After the Roman period, the city passed into the hands of the Eastern Roman Empire, later experiencing invasions by Goths, Huns, and Avars. From the late 9th century, during the rise of the First Bulgarian Empire, the city became known as Sredets, a Slavic name meaning “the middle” or “central place,” referring to its geographic position in the Balkan Peninsula. This name remained in common use throughout the Middle Ages.

The modern name Sofia came into use around the 14th century and is derived from the Church of Saint Sophia, one of the oldest Christian churches in the city. The word sofia in Greek means “wisdom”, and the church’s prominence led local inhabitants to associate the entire urban area with it. The name gradually replaced Sredets, becoming standard by the time the Ottomans conquered the region in 1385.

Under the Ottoman Empire, Sofia served as a major administrative and commercial centre on the road between Constantinople and Central Europe. Its diverse population, markets, mosques, and caravanserais gave it a cosmopolitan character. After nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule, Bulgaria regained independence in 1878, and Sofia was chosen as the national capital the following year due to its central location, growing population, and symbolic links to Bulgarian medieval heritage.

In the 20th century, Sofia expanded rapidly, enduring bombings during World War II and major reconstruction during the communist era. Since the fall of communism in 1989, the city has transformed into a modern European capital while preserving layers of Thracian, Roman, medieval, Ottoman, and modern Bulgarian history.

A walk through Sofia’s city centre leads past the golden domes of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, followed by the early-Christian Saint Sofia Church that inspired the city’s name. Nearby stands the elegant Russian Church, known for its green-and-gold spires. Visitors can also step inside the National Archaeological Museum, housed in a former Ottoman mosque and filled with Thracian and medieval treasures. The stroll naturally ends on Vitosha Boulevard, a lively pedestrian street lined with shops, cafés, and mountain views.

The Thracian tribe Serdi established a settlement here in the 1st millennium BCE, giving rise to the city’s early name Serdica. When the Roman Empire expanded into the region in the 1st century CE, Serdica became an important provincial centre, protected by strong walls and adorned with public buildings, baths, a forum, and an amphitheatre.

After the Roman period, the city passed into the hands of the Eastern Roman Empire, later experiencing invasions by Goths, Huns, and Avars. From the late 9th century, during the rise of the First Bulgarian Empire, the city became known as Sredets, a Slavic name meaning “the middle” or “central place,” referring to its geographic position in the Balkan Peninsula. This name remained in common use throughout the Middle Ages.

The modern name Sofia came into use around the 14th century and is derived from the Church of Saint Sophia, one of the oldest Christian churches in the city. The word sofia in Greek means “wisdom”, and the church’s prominence led local inhabitants to associate the entire urban area with it. The name gradually replaced Sredets, becoming standard by the time the Ottomans conquered the region in 1385.

Under the Ottoman Empire, Sofia served as a major administrative and commercial centre on the road between Constantinople and Central Europe. Its diverse population, markets, mosques, and caravanserais gave it a cosmopolitan character. After nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule, Bulgaria regained independence in 1878, and Sofia was chosen as the national capital the following year due to its central location, growing population, and symbolic links to Bulgarian medieval heritage.

In the 20th century, Sofia expanded rapidly, enduring bombings during World War II and major reconstruction during the communist era. Since the fall of communism in 1989, the city has transformed into a modern European capital while preserving layers of Thracian, Roman, medieval, Ottoman, and modern Bulgarian history.

A walk through Sofia’s city centre leads past the golden domes of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, followed by the early-Christian Saint Sofia Church that inspired the city’s name. Nearby stands the elegant Russian Church, known for its green-and-gold spires. Visitors can also step inside the National Archaeological Museum, housed in a former Ottoman mosque and filled with Thracian and medieval treasures. The stroll naturally ends on Vitosha Boulevard, a lively pedestrian street lined with shops, cafés, and mountain views.

How it works: Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" from Apple App Store or Google Play Store to your mobile phone or tablet. The app turns your mobile device into a personal tour guide and its built-in GPS navigation functions guide you from one tour stop to next. The app works offline, so no data plan is needed when traveling abroad.

Sofia Introduction Walking Tour Map

Guide Name: Sofia Introduction Walking Tour

Guide Location: Bulgaria » Sofia (See other walking tours in Sofia)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 13

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.6 Km or 1.6 Miles

Author: DanaOffice

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

Guide Location: Bulgaria » Sofia (See other walking tours in Sofia)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 13

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.6 Km or 1.6 Miles

Author: DanaOffice

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

- Alexander Nevsky Cathedral

- Saint Sofia Church

- Russian Church

- Prince Alexander of Battenberg Square

- National Archaeological Museum

- Church of Saint George

- Banya Bashi Mosque

- Central Sofia Market Hall

- Sofia Synagogue

- Pirotska Street

- Church of St. Petka of the Saddlers

- St. Nedelya Church

- Vitosha Boulevard

1) Alexander Nevsky Cathedral (must see)

Construction of Sofia’s Alexander Nevsky Cathedral was dedicated to the Russian soldiers who died in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878— the conflict that finally brought an end to centuries of Ottoman rule in Bulgaria. The cathedral takes its name from Saint Alexander Nevsky, the 13th-century prince whose title “Nevsky” refers to his famed victory over Swedish forces at the Battle of the Neva River in 1240.

The cathedral’s design was created by Alexander N. Pomerantsev, a Russian architect known for his eclectic style. He envisioned a grand Neo-Byzantine cross-domed basilica, drawing inspiration from early Eastern Orthodox architecture. Multiple domes rise above the structure, culminating in a uppermost dome sheathed in real gold. With its arches and monumental presence, the cathedral is often described as one of the largest Orthodox church buildings in the world.

If you stand on the square in front of the cathedral and look up, you will see a gold dome above the bell tower. The bell tower holds twelve bells weighing a total of 23 tons. The larger central golden dome behind it reaches 148 feet in height, while the nave roof spans an impressive 92 feet. As you step inside, you will notice its vast interior—covering 34,000 square feet—and said to be able to accommodate up to 5,000 worshipers.

One of the treasures inside is a pair if royal thrones located on a raised platform in front of the iconostasis. Above the thrones, in the arch, is a mosaic portrait of King Ferdinand and Queen Eleonore in full ceremonial robes, holding a model of the cathedral. Near the altar, a reliquary displays a rib believed to belong to Saint Alexander Nevsky himself. It is recommended that you visit the crypt museum beneath the cathedral, as it houses one of Europe’s largest collections of Orthodox icons.

The cathedral also preserves notable historical artifacts and craftsmanship. The Italian-made marble iconostasis remains one of its most admired features. The crypt museum, open separately from the main sanctuary, displays over 300 icons spanning the 9th to the 19th century, offering one of the most comprehensive surveys of Orthodox icon painting in Europe.

The cathedral’s design was created by Alexander N. Pomerantsev, a Russian architect known for his eclectic style. He envisioned a grand Neo-Byzantine cross-domed basilica, drawing inspiration from early Eastern Orthodox architecture. Multiple domes rise above the structure, culminating in a uppermost dome sheathed in real gold. With its arches and monumental presence, the cathedral is often described as one of the largest Orthodox church buildings in the world.

If you stand on the square in front of the cathedral and look up, you will see a gold dome above the bell tower. The bell tower holds twelve bells weighing a total of 23 tons. The larger central golden dome behind it reaches 148 feet in height, while the nave roof spans an impressive 92 feet. As you step inside, you will notice its vast interior—covering 34,000 square feet—and said to be able to accommodate up to 5,000 worshipers.

One of the treasures inside is a pair if royal thrones located on a raised platform in front of the iconostasis. Above the thrones, in the arch, is a mosaic portrait of King Ferdinand and Queen Eleonore in full ceremonial robes, holding a model of the cathedral. Near the altar, a reliquary displays a rib believed to belong to Saint Alexander Nevsky himself. It is recommended that you visit the crypt museum beneath the cathedral, as it houses one of Europe’s largest collections of Orthodox icons.

The cathedral also preserves notable historical artifacts and craftsmanship. The Italian-made marble iconostasis remains one of its most admired features. The crypt museum, open separately from the main sanctuary, displays over 300 icons spanning the 9th to the 19th century, offering one of the most comprehensive surveys of Orthodox icon painting in Europe.

2) Saint Sofia Church (must see)

Saint Sofia Church dates to the 6th century, built during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, placing it in the same era as Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia. Like its famous counterpart, it was turned into a mosque under Ottoman rule—yet unlike Hagia Sophia, it eventually returned to Christian worship, reclaiming its original identity.

It is the second-oldest church in the Bulgarian capital. In the 14th century, its name—Sofia, meaning “Wisdom”—was adopted by the city itself. If you are admiring the church from the outside, you'll see its rectangular basilica form, with undecorated walls made from red brick and small, evenly spaced window openings. You can notice a simple construction, with a low and pitched roofline, without domes, towers, or a bell tower.

During its conversion into a mosque in the 16th century, the church gained two minarets. In the 19th century, two earthquakes struck the building—one minaret collapsed, and the mosque was abandoned soon after. Large-scale restoration only began in 1900, following the end of Ottoman rule.

When you step inside the church, you’ll see the same simple red-brick walls. During the Ottoman period, when the church was converted into a mosque, its medieval frescoes were lost. Head to the Underground Museum, where layers of buildings from across the centuries are exposed, reaching back as far as the 3rd century AD. Here, excavations have revealed an extensive necropolis beneath and around the basilica, with numerous tombs, crypts, and remnants of earlier sanctuaries now accessible to visitors. Pay attention to the floors decorated with early Christian mosaics featuring detailed animal and floral patterns.

For centuries, local tradition has held that Saint Sofia’s protective power guarded the church through invasions, epidemics, and natural disasters—perhaps part of the reason it remains so well preserved today. In Orthodox iconography, Sofia appears as a woman symbolizing Divine Wisdom, standing above the allegorical figures of Faith, Hope, and Love, linking the church’s name to one of Christianity’s most enduring spiritual ideals.

It is the second-oldest church in the Bulgarian capital. In the 14th century, its name—Sofia, meaning “Wisdom”—was adopted by the city itself. If you are admiring the church from the outside, you'll see its rectangular basilica form, with undecorated walls made from red brick and small, evenly spaced window openings. You can notice a simple construction, with a low and pitched roofline, without domes, towers, or a bell tower.

During its conversion into a mosque in the 16th century, the church gained two minarets. In the 19th century, two earthquakes struck the building—one minaret collapsed, and the mosque was abandoned soon after. Large-scale restoration only began in 1900, following the end of Ottoman rule.

When you step inside the church, you’ll see the same simple red-brick walls. During the Ottoman period, when the church was converted into a mosque, its medieval frescoes were lost. Head to the Underground Museum, where layers of buildings from across the centuries are exposed, reaching back as far as the 3rd century AD. Here, excavations have revealed an extensive necropolis beneath and around the basilica, with numerous tombs, crypts, and remnants of earlier sanctuaries now accessible to visitors. Pay attention to the floors decorated with early Christian mosaics featuring detailed animal and floral patterns.

For centuries, local tradition has held that Saint Sofia’s protective power guarded the church through invasions, epidemics, and natural disasters—perhaps part of the reason it remains so well preserved today. In Orthodox iconography, Sofia appears as a woman symbolizing Divine Wisdom, standing above the allegorical figures of Faith, Hope, and Love, linking the church’s name to one of Christianity’s most enduring spiritual ideals.

3) Russian Church (must see)

The final years of Ottoman rule in Bulgaria brought dramatic changes to Sofia’s skyline. In 1882, the Saray Mosque was demolished, leaving an open plot of land directly beside the Russian Embassy. With Bulgaria newly liberated after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the location seemed almost destined for an official Russian church—a symbol of gratitude and alliance.

The church was dedicated to Saint Nicholas the Miracle-Maker, the patron saint of Tsar Nicholas II. Russian architect Mikhail Preobrazhenski designed it in a distinct Russian Revival style. Its exterior shimmers with multicolored tiles, while the interior frescoes were painted by the same team responsible for the murals in the grand cathedral next door. Above the church rise five gold-plated domes, accompanied by a carillon gifted by Tsar Nicholas II.

Construction began in 1907, and the church was consecrated in 1914, just as the Russian Empire was approaching its own collapse. Remarkably, the Russian Church remained open throughout Bulgaria’s Communist period. While many religious institutions faced pressure or closure, this one continued to hold services under close, but ultimately non-interfering, state supervision.

One of the most significant features of the church lies below ground: the crypt, which contains the relics of Saint Archbishop Seraphim Sobolev. As the leading figure of Russian Orthodoxy in Bulgaria from 1921 until his death in 1950, he became a beloved spiritual guide. After his canonization, accounts of miracles began to circulate, and visitors today still leave handwritten notes at his tomb, asking for help or blessing.

The church has two entrances, each marked by a meaningful image. The south entrance on Tsar Osvoboditel Boulevard bears the face of Saint Nicholas, while the north entrance, opening toward a nearby park, features the likeness of Alexander Nevsky. For visitors interested in learning more, guided tours are available with advance arrangement.

The church was dedicated to Saint Nicholas the Miracle-Maker, the patron saint of Tsar Nicholas II. Russian architect Mikhail Preobrazhenski designed it in a distinct Russian Revival style. Its exterior shimmers with multicolored tiles, while the interior frescoes were painted by the same team responsible for the murals in the grand cathedral next door. Above the church rise five gold-plated domes, accompanied by a carillon gifted by Tsar Nicholas II.

Construction began in 1907, and the church was consecrated in 1914, just as the Russian Empire was approaching its own collapse. Remarkably, the Russian Church remained open throughout Bulgaria’s Communist period. While many religious institutions faced pressure or closure, this one continued to hold services under close, but ultimately non-interfering, state supervision.

One of the most significant features of the church lies below ground: the crypt, which contains the relics of Saint Archbishop Seraphim Sobolev. As the leading figure of Russian Orthodoxy in Bulgaria from 1921 until his death in 1950, he became a beloved spiritual guide. After his canonization, accounts of miracles began to circulate, and visitors today still leave handwritten notes at his tomb, asking for help or blessing.

The church has two entrances, each marked by a meaningful image. The south entrance on Tsar Osvoboditel Boulevard bears the face of Saint Nicholas, while the north entrance, opening toward a nearby park, features the likeness of Alexander Nevsky. For visitors interested in learning more, guided tours are available with advance arrangement.

4) Prince Alexander of Battenberg Square

Alexander Battenberg Square has long been one of Sofia’s most prominent public spaces, evolving through several political eras and names. During the Communist period, it was known as September 9th Square, commemorating the 1944 government overthrow. Before that, it carried the name Tsar’s Square, thanks to the royal palace that stood beside it—today home to the National Art Gallery. The square also once housed the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum, one of the most recognizable symbols of Communist Bulgaria.

Georgi Dimitrov, the country’s first Communist leader, died in 1949 and was placed in the Mausoleum with full honours. His successor, Vasil Kolarov, who died the following year, received a niche in the east wall. From its earliest days, the Mausoleum faced repeated attempts to destroy it. After Bulgaria’s transition to democracy, the post-Communist UDF government finally demolished it, succeeding only after four separate explosive attempts.

The square’s name honours Alexander of Battenberg, the first Prince of the Principality of Bulgaria. He became prince in 1879, elected by the Bulgarian Grand National Assembly during a period when Bulgaria still held autonomous status within the waning Ottoman Empire. His refusal to conform to Russian interests eventually led to his forced abdication in 1886, but his name endures in one of Sofia’s most significant civic spaces.

Today, the square is Sofia’s premier setting for outdoor events and concerts. While military parades were common during the Communist era, the most notable modern parade held here is the Bulgarian Armed Forces Day Parade, celebrated on May 6th each year.

Georgi Dimitrov, the country’s first Communist leader, died in 1949 and was placed in the Mausoleum with full honours. His successor, Vasil Kolarov, who died the following year, received a niche in the east wall. From its earliest days, the Mausoleum faced repeated attempts to destroy it. After Bulgaria’s transition to democracy, the post-Communist UDF government finally demolished it, succeeding only after four separate explosive attempts.

The square’s name honours Alexander of Battenberg, the first Prince of the Principality of Bulgaria. He became prince in 1879, elected by the Bulgarian Grand National Assembly during a period when Bulgaria still held autonomous status within the waning Ottoman Empire. His refusal to conform to Russian interests eventually led to his forced abdication in 1886, but his name endures in one of Sofia’s most significant civic spaces.

Today, the square is Sofia’s premier setting for outdoor events and concerts. While military parades were common during the Communist era, the most notable modern parade held here is the Bulgarian Armed Forces Day Parade, celebrated on May 6th each year.

5) National Archaeological Museum (must see)

The National Archaeological Museum occupies the building of the former Grand Mahmut Pasha Mosque, the largest and oldest surviving Ottoman mosque in Sofia. Established in 1893, the museum was the first institution of its kind in Bulgaria, led by its inaugural director, the Czech archaeologist and scholar Václav Dobruský. Although modern galleries have been added through the years, the museum still operates inside its original stone structure.

The Grand Mahmut Pasha Mosque, rather than being converted into a church after the end of Ottoman rule, it was repurposed as a library and later chosen to house the new national museum. Completed in 1494, it had been commissioned by Grand Vizier Veli Mahmud Pasha, a member of the Byzantine Angelos family of Thessaloniki who was captured as a child, raised within the Ottoman system, and elevated to high office after distinguishing himself during the 1456 siege of Belgrade.

Visiting the museum, you explore five main exhibition halls: the Central Hall, Prehistory Hall, Middle Ages Hall, Treasury Hall, and a gallery for rotating temporary exhibitions. It is recommend that you start from the Prehistory Hall, located on the lower floor of the north wing. There, you can observe objects ranging from 1,600,000 BC to 1,600 BC, tracing human presence from the earliest Paleolithic evidence to the dawn of complex societies.

in the eastern wing, you can access the Treasury Hall, showcasing rare and valuable items from the Bronze Age through late Antiquity, including intricate metalwork and ritual artifacts. The vast Main Hall on the first floor presents collections from ancient Greece and Rome, while the Medieval Section on the second floor explores Bulgaria’s early Christian and medieval heritage.

The Grand Mahmut Pasha Mosque, rather than being converted into a church after the end of Ottoman rule, it was repurposed as a library and later chosen to house the new national museum. Completed in 1494, it had been commissioned by Grand Vizier Veli Mahmud Pasha, a member of the Byzantine Angelos family of Thessaloniki who was captured as a child, raised within the Ottoman system, and elevated to high office after distinguishing himself during the 1456 siege of Belgrade.

Visiting the museum, you explore five main exhibition halls: the Central Hall, Prehistory Hall, Middle Ages Hall, Treasury Hall, and a gallery for rotating temporary exhibitions. It is recommend that you start from the Prehistory Hall, located on the lower floor of the north wing. There, you can observe objects ranging from 1,600,000 BC to 1,600 BC, tracing human presence from the earliest Paleolithic evidence to the dawn of complex societies.

in the eastern wing, you can access the Treasury Hall, showcasing rare and valuable items from the Bronze Age through late Antiquity, including intricate metalwork and ritual artifacts. The vast Main Hall on the first floor presents collections from ancient Greece and Rome, while the Medieval Section on the second floor explores Bulgaria’s early Christian and medieval heritage.

6) Church of Saint George (must see)

The Church of Saint George is a red brick rotunda dating from the 4th century. Originally built as part of a Roman bath complex in ancient Sofia, it is considered the oldest standing building in Bulgaria’s capital. The structure was converted into a Christian church in late Antiquity and today functions under the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.

The rotunda is cylindrical, set on a square base, and topped with a dome. Inside are remarkable frescoes from the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries, with earlier layers dating back to the 10th century. A ring of 22 prophets surrounds the dome. These paintings were covered during the Ottoman period—when the church was used as a mosque—and rediscovered during restoration work in the 20th century.

The dome rises about 45 feet above the floor. Five distinct layers of frescoes have been documented. The oldest, Roman-Byzantine in style, features floral and geometric ornament. Above this is a medieval Bulgarian layer with 10th-century angels. The third layer is a frieze of prophets and scenes such as the Ascension and the Assumption. The fourth contains a 14th-century portrait of a bishop, while the final layer shows Islamic decoration added during Ottoman rule.

The church sits within a courtyard surrounded by former government buildings from the 1950s. On significant occasions, the rotunda is used for military ceremonies and concerts featuring classical or sacred music. A small archaeological zone around the entrance preserves remains of Roman streets, buildings, and an early Christian baptistery, offering visitors a rare glimpse of ancient Sofia.

The rotunda is cylindrical, set on a square base, and topped with a dome. Inside are remarkable frescoes from the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries, with earlier layers dating back to the 10th century. A ring of 22 prophets surrounds the dome. These paintings were covered during the Ottoman period—when the church was used as a mosque—and rediscovered during restoration work in the 20th century.

The dome rises about 45 feet above the floor. Five distinct layers of frescoes have been documented. The oldest, Roman-Byzantine in style, features floral and geometric ornament. Above this is a medieval Bulgarian layer with 10th-century angels. The third layer is a frieze of prophets and scenes such as the Ascension and the Assumption. The fourth contains a 14th-century portrait of a bishop, while the final layer shows Islamic decoration added during Ottoman rule.

The church sits within a courtyard surrounded by former government buildings from the 1950s. On significant occasions, the rotunda is used for military ceremonies and concerts featuring classical or sacred music. A small archaeological zone around the entrance preserves remains of Roman streets, buildings, and an early Christian baptistery, offering visitors a rare glimpse of ancient Sofia.

7) Banya Bashi Mosque

The Banya Bashi Mosque, meaning “Many Baths”, reflects the thermal springs beneath it, which can still be seen rising from vents near the building on cool mornings. Completed in 1566, the mosque was designed by Mimar Sinan, the most renowned architect of the Ottoman Empire.

The mosque was commissioned by Kadı Seyfullah Efendi, the city’s chief judge, in memory of his late wife. The main structure is crowned by a single large central dome, measuring 15 meters in diameter. At the front of the complex stands an annex built as a memorial space, topped with three smaller domes. A slender minaret rises beside the mosque, and the entrance features an arcade supported by three stone pillars.

Inside, the prayer hall forms a cube-shaped space beneath the soaring dome. The interior is adorned with floral motifs, geometric designs, and Arabic calligraphy, typical of 16th-century Ottoman aesthetics. Notable details include aquamarine tiles on the eastern wall and a tile panel depicting the Kaaba in Mecca, connecting the worship space to the wider Islamic world.

The mosque can accommodate about 700 worshippers, with Friday prayers drawing the largest gatherings. Today, Banya Bashi is the only functioning mosque in Sofia, preserving both the spiritual life and architectural heritage of the city’s Ottoman past.

The mosque was commissioned by Kadı Seyfullah Efendi, the city’s chief judge, in memory of his late wife. The main structure is crowned by a single large central dome, measuring 15 meters in diameter. At the front of the complex stands an annex built as a memorial space, topped with three smaller domes. A slender minaret rises beside the mosque, and the entrance features an arcade supported by three stone pillars.

Inside, the prayer hall forms a cube-shaped space beneath the soaring dome. The interior is adorned with floral motifs, geometric designs, and Arabic calligraphy, typical of 16th-century Ottoman aesthetics. Notable details include aquamarine tiles on the eastern wall and a tile panel depicting the Kaaba in Mecca, connecting the worship space to the wider Islamic world.

The mosque can accommodate about 700 worshippers, with Friday prayers drawing the largest gatherings. Today, Banya Bashi is the only functioning mosque in Sofia, preserving both the spiritual life and architectural heritage of the city’s Ottoman past.

8) Central Sofia Market Hall

Even though its official English name is Central Sofia Hall, most people in the city simply call it The Market Hall. Designed by Bulgarian architect Naum Torbov, it first opened its doors in 1911 and quickly became one of Sofia’s busiest commercial hubs. When it first opened, this was one of the very few buildings in Sofia to combine commercial space with modern infrastructure, including refrigeration facilities.

For decades, the city rented out roughly 170 small shops inside the building—until 1950, when it shifted to full public use. The market continued to thrive until 1988, when it closed for long-planned renovations, reopening in 2000. Today, it employs over 1,000 people and stretches across three floors filled with food stalls, fast-food counters, clothing boutiques, jewelry stands, and everyday accessories. Torbov’s original design has been carefully preserved, and many still consider this building his masterpiece.

Architecturally, the Market Hall is a blend of Neo-Renaissance style, mixed with Neo-Byzantine and Neo-Baroque touches. Above the main entrance, you’ll spot Sofia’s coat of arms, created by artist Haralampi Tachev, while the clock tower—complete with three clock dials—keeps watch over the boulevard. The hall has four entrances, though only some are in use today.

For decades, the city rented out roughly 170 small shops inside the building—until 1950, when it shifted to full public use. The market continued to thrive until 1988, when it closed for long-planned renovations, reopening in 2000. Today, it employs over 1,000 people and stretches across three floors filled with food stalls, fast-food counters, clothing boutiques, jewelry stands, and everyday accessories. Torbov’s original design has been carefully preserved, and many still consider this building his masterpiece.

Architecturally, the Market Hall is a blend of Neo-Renaissance style, mixed with Neo-Byzantine and Neo-Baroque touches. Above the main entrance, you’ll spot Sofia’s coat of arms, created by artist Haralampi Tachev, while the clock tower—complete with three clock dials—keeps watch over the boulevard. The hall has four entrances, though only some are in use today.

9) Sofia Synagogue

The Sofia Synagogue serves the spiritual needs of Sofia’s Sephardic Jewish community, being the largest synagogue in Southeastern Europe and one of only two still operating in Bulgaria. Designed by the Austrian architect Friedrich Grünanger, it opened in 1909 in the presence of Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria.

Its design was inspired by the Moorish-style Leopoldstadt Temple of Vienna and was built on the site of an earlier synagogue. The new building formed part of a broader effort to reorganize and modernize Bulgaria’s Jewish community at the start of the 20th century. It can accommodate up to 1,300 worshippers, and its central chandelier weighs nearly two tons.

In reality, attendance rarely fills the space. Although the synagogue stands within Sofia’s so-called “Square of Tolerance”, Bulgaria’s historical record of tolerance has been complicated, and most of the country’s Jews eventually emigrated to Israel.

Architecturally, the Sofia Synagogue is a fine example of Moorish Revival style, blended with influences from the Vienna Secession art movement. Venetian elements appear on the façade, while the structure is crowned by an octagonal dome. Inside, visitors can admire Carrara marble columns, Venetian mosaics, and carved wooden details.

Since 1992, the building has also housed the Jewish Museum of History, which documents the story of Jewish life in Bulgaria, including both the Holocaust period and the rescue of Bulgaria’s Jewish population. A small gift shop is also available for visitors.

Its design was inspired by the Moorish-style Leopoldstadt Temple of Vienna and was built on the site of an earlier synagogue. The new building formed part of a broader effort to reorganize and modernize Bulgaria’s Jewish community at the start of the 20th century. It can accommodate up to 1,300 worshippers, and its central chandelier weighs nearly two tons.

In reality, attendance rarely fills the space. Although the synagogue stands within Sofia’s so-called “Square of Tolerance”, Bulgaria’s historical record of tolerance has been complicated, and most of the country’s Jews eventually emigrated to Israel.

Architecturally, the Sofia Synagogue is a fine example of Moorish Revival style, blended with influences from the Vienna Secession art movement. Venetian elements appear on the façade, while the structure is crowned by an octagonal dome. Inside, visitors can admire Carrara marble columns, Venetian mosaics, and carved wooden details.

Since 1992, the building has also housed the Jewish Museum of History, which documents the story of Jewish life in Bulgaria, including both the Holocaust period and the rescue of Bulgaria’s Jewish population. A small gift shop is also available for visitors.

10) Pirotska Street

The first pedestrianized street in Sofia, Pirotska Street has a history rooted in Bulgaria’s early years of independence. It emerged in the late 19th century as Sofia rapidly expanded beyond its old Ottoman-era core. By the early 1900s, it had become a busy commercial street lined with small workshops, family stores, and bakeries—many of which were owned by local craftsmen and merchants from across the region.

Today, you can begin your stroll with a fresh banitsa—a flaky Bulgarian pastry filled with cheese— from a local bakery before heading toward Halite, the Central Market Hall, built in 1911 and still bustling with food stalls below and small shops above. Pirotska remains packed with places to explore—over 100 shops, cafés, restaurants, and market-style stands offering clothing, shoes, cosmetics, artisanal goods, and everyday necessities, often at prices lower than Sofia’s more upscale shopping avenues.

Unlike the big-brand shopping streets, most shops here feature Bulgarian-made goods or imports from nearby countries. You might find a traditional bakery next to a leather shop, a tiny bookstore, or a courtyard café hidden down a side passage. Historically, Pirotska also bordered Sofia’s old Jewish quarter, and traces of that heritage linger in nearby buildings and side streets.

Today, you can begin your stroll with a fresh banitsa—a flaky Bulgarian pastry filled with cheese— from a local bakery before heading toward Halite, the Central Market Hall, built in 1911 and still bustling with food stalls below and small shops above. Pirotska remains packed with places to explore—over 100 shops, cafés, restaurants, and market-style stands offering clothing, shoes, cosmetics, artisanal goods, and everyday necessities, often at prices lower than Sofia’s more upscale shopping avenues.

Unlike the big-brand shopping streets, most shops here feature Bulgarian-made goods or imports from nearby countries. You might find a traditional bakery next to a leather shop, a tiny bookstore, or a courtyard café hidden down a side passage. Historically, Pirotska also bordered Sofia’s old Jewish quarter, and traces of that heritage linger in nearby buildings and side streets.

11) Church of St. Petka of the Saddlers

The Church of Saint Petka of the Saddlers is a small medieval structure built of thick brick-and-stone walls nearly three feet wide. It consists of a single nave covered by a cylindrical vault and a hemispherical apse. The church is dedicated to Saint Petka, also known as Parascheva of the Balkans, an 11th-century ascetic born near the Sea of Marmara who became widely venerated throughout the region.

The name “of the Saddlers” dates back to the Middle Ages, when the local guild of saddlemakers adopted Saint Petka as their patron. The building’s modest size reflects Ottoman law, which at the time forbade churches from rising higher than an ordinary house, resulting in a humble but enduring place of worship.

Inside, the church’s most interesting feature is its collection of murals, painted over several centuries. These frescoes mostly depict Biblical scenes, with the earliest dating to the 14th century and later layers added in the 15th and 16th centuries—creating a visual record of evolving artistic styles and devotional practices.

A persistent local legend adds another layer of intrigue: it is said that Vasil Levski, Bulgaria’s national revolutionary hero, was secretly buried in the crypt beneath the church. Although no conclusive evidence has ever been found, the story remains deeply woven into the site’s identity and popular memory.

The name “of the Saddlers” dates back to the Middle Ages, when the local guild of saddlemakers adopted Saint Petka as their patron. The building’s modest size reflects Ottoman law, which at the time forbade churches from rising higher than an ordinary house, resulting in a humble but enduring place of worship.

Inside, the church’s most interesting feature is its collection of murals, painted over several centuries. These frescoes mostly depict Biblical scenes, with the earliest dating to the 14th century and later layers added in the 15th and 16th centuries—creating a visual record of evolving artistic styles and devotional practices.

A persistent local legend adds another layer of intrigue: it is said that Vasil Levski, Bulgaria’s national revolutionary hero, was secretly buried in the crypt beneath the church. Although no conclusive evidence has ever been found, the story remains deeply woven into the site’s identity and popular memory.

12) St. Nedelya Church (must see)

Saint Nedelya Church, meaning “Holy Sunday”, reflects centuries of Christian worship and linguistic tradition. Built in the medieval period, the church has been destroyed, rebuilt, expanded, and even targeted in a deadly political attack. The first version of Saint Nedelya is believed to have been built in the 10th century. Its foundation was of stone, but the rest of the structure was wooden. By the 18th century, it had become a bishop’s residence and the resting place of Serbian King Stefan Milutin, whose relics had been moved several times since 1460 before finding a home here.

The old church was demolished in 1856 to make way for a larger cathedral. Construction faced setbacks, including damage from an earthquake in 1858, but the new church was completed in 1863. In May 1867, it was inaugurated in front of an enormous crowd of 20,000 people. A new belfry was added in 1879 to house a carillon donated by Prince Alexander M. Dondukov-Korsakov.

In 1925, Saint Nedelya became the site of the deadliest political attack in Bulgarian history, when Communist militants bombed the church during a state funeral, killing more than 150 people. The church was rebuilt between 1927 and 1933, preserving its size while adding a central dome that rises 93 feet above the floor.

Renovation continued into modern times. By 1994, the floor had been replaced and the north colonnade reglazed, and in 2000 the façade received a full cleaning. Today, Saint Nedelya remains an active place of worship and a powerful symbol of Sofia’s endurance through centuries of upheaval.

The old church was demolished in 1856 to make way for a larger cathedral. Construction faced setbacks, including damage from an earthquake in 1858, but the new church was completed in 1863. In May 1867, it was inaugurated in front of an enormous crowd of 20,000 people. A new belfry was added in 1879 to house a carillon donated by Prince Alexander M. Dondukov-Korsakov.

In 1925, Saint Nedelya became the site of the deadliest political attack in Bulgarian history, when Communist militants bombed the church during a state funeral, killing more than 150 people. The church was rebuilt between 1927 and 1933, preserving its size while adding a central dome that rises 93 feet above the floor.

Renovation continued into modern times. By 1994, the floor had been replaced and the north colonnade reglazed, and in 2000 the façade received a full cleaning. Today, Saint Nedelya remains an active place of worship and a powerful symbol of Sofia’s endurance through centuries of upheaval.

13) Vitosha Boulevard (must see)

Have you seen Mount Vitosha while visiting the city? But did you know this is the mountain from which Vitosha Boulevard takes its name from? Today, it serves as the city’s main shopping and commercial artery, running from Saint Nedelya Square all the way to Southern Park. Along its length, visitors encounter a concentration of luxury boutiques, fashionable cafés, elegant restaurants, and lively bars—especially popular for open-air dining in summer and illuminated evening strolls.

Starting near Saint Nedelya Square and heading south toward Southern Park, you’ll come across names like Versace, D&G, La Perla, Lacoste, Armani, Tommy Hilfiger, Hugo Boss, among others. Most of these stores are set directly along the main pedestrian stretch, making them easy to explore as you walk the boulevard end to end. According to a recent 2024 report, Vitosha Boulevard now ranks among the top 60 most expensive shopping streets in the world.

Before Bulgaria’s liberation from Ottoman's rule in 1878, the street was lined with small one-story houses. Between the two World Wars, it transformed into a major commercial artery marked by larger-scale construction and European architectural influences. Near the northern end, close to Saint Nedelya Square, stands the imposing Palace of Justice.

Farther along the boulevard, as you head toward the park, you’ll pass the former home of Bulgarian Symbolist poet Peyo Yavorov, located at Georgi S. Rakovski 136—a three-story building with a light-yellow facade. Continue onward to the southern stretch where the National Palace of Culture dominates the skyline. Along this route, you’ll also come across the corner famously known as “The Pharmacy,” part of the Grand Hotel Sofia. Once a favored meeting place for writers and artists, the space within the hotel has since been renovated and repurposed over the years. The hotel building itself is a protected architectural landmark in Sofia.

In 2007, a renovation project was launched to restore the elegant look of 1930s Sofia. Historical street lamps, benches, and Art Nouveau-style kiosks were added, along with new green spaces, fountains, outdoor bars, and a clock tower near Saint Nedelya Cathedral—displaying the time in major world capitals.

One fascinating detail is that beneath Vitosha Boulevard lie underground remains of ancient Sofia, including Roman streets and fragments of early urban life. In some places, you can glimpse these ruins protected by glass panels from the surface.

Starting near Saint Nedelya Square and heading south toward Southern Park, you’ll come across names like Versace, D&G, La Perla, Lacoste, Armani, Tommy Hilfiger, Hugo Boss, among others. Most of these stores are set directly along the main pedestrian stretch, making them easy to explore as you walk the boulevard end to end. According to a recent 2024 report, Vitosha Boulevard now ranks among the top 60 most expensive shopping streets in the world.

Before Bulgaria’s liberation from Ottoman's rule in 1878, the street was lined with small one-story houses. Between the two World Wars, it transformed into a major commercial artery marked by larger-scale construction and European architectural influences. Near the northern end, close to Saint Nedelya Square, stands the imposing Palace of Justice.

Farther along the boulevard, as you head toward the park, you’ll pass the former home of Bulgarian Symbolist poet Peyo Yavorov, located at Georgi S. Rakovski 136—a three-story building with a light-yellow facade. Continue onward to the southern stretch where the National Palace of Culture dominates the skyline. Along this route, you’ll also come across the corner famously known as “The Pharmacy,” part of the Grand Hotel Sofia. Once a favored meeting place for writers and artists, the space within the hotel has since been renovated and repurposed over the years. The hotel building itself is a protected architectural landmark in Sofia.

In 2007, a renovation project was launched to restore the elegant look of 1930s Sofia. Historical street lamps, benches, and Art Nouveau-style kiosks were added, along with new green spaces, fountains, outdoor bars, and a clock tower near Saint Nedelya Cathedral—displaying the time in major world capitals.

One fascinating detail is that beneath Vitosha Boulevard lie underground remains of ancient Sofia, including Roman streets and fragments of early urban life. In some places, you can glimpse these ruins protected by glass panels from the surface.

Walking Tours in Sofia, Bulgaria

Create Your Own Walk in Sofia

Creating your own self-guided walk in Sofia is easy and fun. Choose the city attractions that you want to see and a walk route map will be created just for you. You can even set your hotel as the start point of the walk.

Communist Era Landmarks Walk

In the not-so-distant past Bulgaria was part of the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc. Today, this is one of the few countries where you can still find numerous relics of the Communist era manifested in monumental architectural landmarks. Concrete and metal were the main materials as a symbol of the industrialized nation, and the size was important too as a common architectural characteristic prescribed by... view more

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 6.6 Km or 4.1 Miles

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 6.6 Km or 4.1 Miles

Useful Travel Guides for Planning Your Trip

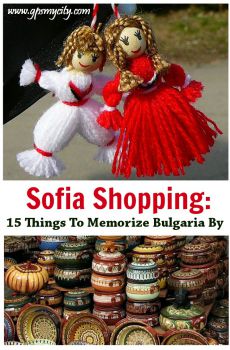

Sofia Shopping: 15 Things To Memorize Bulgaria By

Increasingly popular tourist destination in recent years, Bulgaria has opened up to the outer world, revealing colorful identity, manifested in rich craftsmanship, culinary and cultural traditions and history. The country's capital city Sofia is a lovely alloy of Eastern and Western European...

The Most Popular Cities

/ view all